Resident Evil 7: Biohazard marked a radical departure from the series’ past titles, innovating the gameplay with a first person perspective and telling a story that evokes movies such as The Evil Dead and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Some series diehards have made unflattering comparisons to the psychological horror game P.T. or accused Capcom of plagiarizing the cancelled Silent Hill series. Feeling as though the series DNA had been tampered with, they accused the developers of wading into psychological horror without precedent.

To be fair, the detractors were onto something when they said Resident Evil 7 isn’t Resident Evil enough. Something is fundamentally different. Just look at Resident Evil 7’s personal, character driven story compared to classic Resident Evil’s impersonal, plot-driven stories. Ethan, our mundane everyman protagonist, has different motivations than most Resident Evil heroes who are law enforcement agents trying to uphold order and save the world from evil corporations.

Resident Evil 7’s intro cutscene perfectly illustrates this radical shift in tone. The classic exposition-heavy narration explicitly detailing the setting and context for the plot is gone. There’s no overt horror atmosphere, and not a single mention of the Umbrella Corporation. Instead, the time is devoted to the story’s core relationship: the marriage of Ethan and Mia Winters.

What makes Resident Evil 7’s horror so effective is its intimate portrayal of the breakdown of a family unit. Through perverting and distorting the concept of family, the game moves the focus from transient fears of spooky monsters to personal anxieties like abuse, parental neglect, and problem children.

The game immediately sets up the emotional stakes through a video message from Mia:

“Hey baby! I just wanted to send a quick ‘Hello” and “I love you,” Oh, good news! I’m gonna be coming home soon. Yay! I cannot wait to be done with this babysitting job, and come home to my loving husband. I miss you. I gotta get back to work. I love you Ethan. I miss you so much. I’m sending *tons* of kisses. Bye baby!”

You don’t know who Ethan is, but you know his defining relationship. The scene is cast in warm lighting, suggesting a tone of optimism. In a couple dozen words, Mia endears herself to the player with her affection, devotion, and playfulness. This is the ideal relationship. And then it’s taken away from you.

In Mia’s second message, she admits that she lied to you about her babysitting job. She’s in some kind of distress. Her arms have blood and muck on them, and she’s shrouded in darkness. She tells you to stay away. The video sets up a mystery that will continue through the rest of the game: What happened to Mia? What did she do? And can we trust her?

More than creating dramatic tension for the conflict to come, the opening contrasts the ideal and reality of family. Sometimes the people we love fall short of our expectations. We also see this contrast in our protagonist, Ethan. When Ethan learns that Mia is alive he drops everything to go and save her. She’s been missing for three years and he has to know what happened.

Ethan is the perfect protagonist for this story, a family man whose rescue mission relies on the authority of a seven-word email allegedly written by Mia: “Dulvey, Louisiana. Baker Farm. Come get me.” We expect that after a perilous journey, Ethan will defeat the bad guys like a knight in shining armor, and save his love-struck beloved. What happens instead is that Ethan finds Mia within 10 minutes of arriving in a creepy haunted house. Then she tries to stab him to death. Welcome to Resident Evil 7.

The intro climaxes with a game of cat and mouse between an injured Ethan and a supernaturally empowered Mia. The script has been flipped, and now the simple rescue mission (and the Winters’ marriage) is in serious doubt. This literal and metaphorical domestic violence is the heart of Resident Evil 7’s encounter philosophy. The monsters are personal. The first enemy you fight and kill is your wife.

When Ethan buries an ax into Mia’s shoulder, the tone of the scene shifts from terror to tragedy. Her ghoulish face fades, and we see her now too human face express shock and pain before the lights in her eyes go out. You reach for each other, but she falls to the ground. The score shifts to a haunting, subtle piano to emphasize the horror of your actions. What have you done? When Mia returns a few minutes later brandishing a chainsaw, it cements if fact that the classic Resident Evil rules have been thrown out the window.

Resident Evil 7 raises the stakes by giving the main enemies a personal relationship to you. They refer to you by your name and you know theirs. You are no longer some moral authority shooting mindless zombies you don’t know.

The game never lets you forget that there might be people trapped inside the body of the possessed psychopaths out to get you. Victory becomes uncomfortable, and you’re forced to confront the ambiguity of your actions. The second time you defeat Mia, she growls an otherworldly “I love you” before falling to the ground. Later, you can find a videotape where Mia apologizes for trying to kill you: “I just want you to know that wasn’t me. I don’t know what happened. “

You finally get answers through a phone call with Zoe Baker, the daughter of the family least afflicted by the mind-controlling fungus that’s infected Mia.

“My family and I… our bodies are contaminated. I can’t leave the property unless I get it out. And the same goes for Mia… We need the serum. It should clear whatever this stuff is out of the body. As long as you’re not too far gone.”

Zoe tasks you with creating a serum to save her and Mia, allowing the three of you to escape the Baker estate. You should feel empowered by finally having a solution to your predicament, but you can’t help but feel unnerved by your new mission.

The game distorts the classic Resident Evil trope of making a cure by replacing the clinical lab where you typically synthesize the serum with a fetch quest to find dead fetuses. You’re instructed to find a “D-Series” head and arm, implied to be part of failed biological experiments that died during pregnancy. The house where each component of the cure resides is filled with visual motifs showing the perversion of birth. The bridge to the residence is strung up with dirty, broken baby dolls and you can find more mutilated dolls in a cupboard on the second floor.

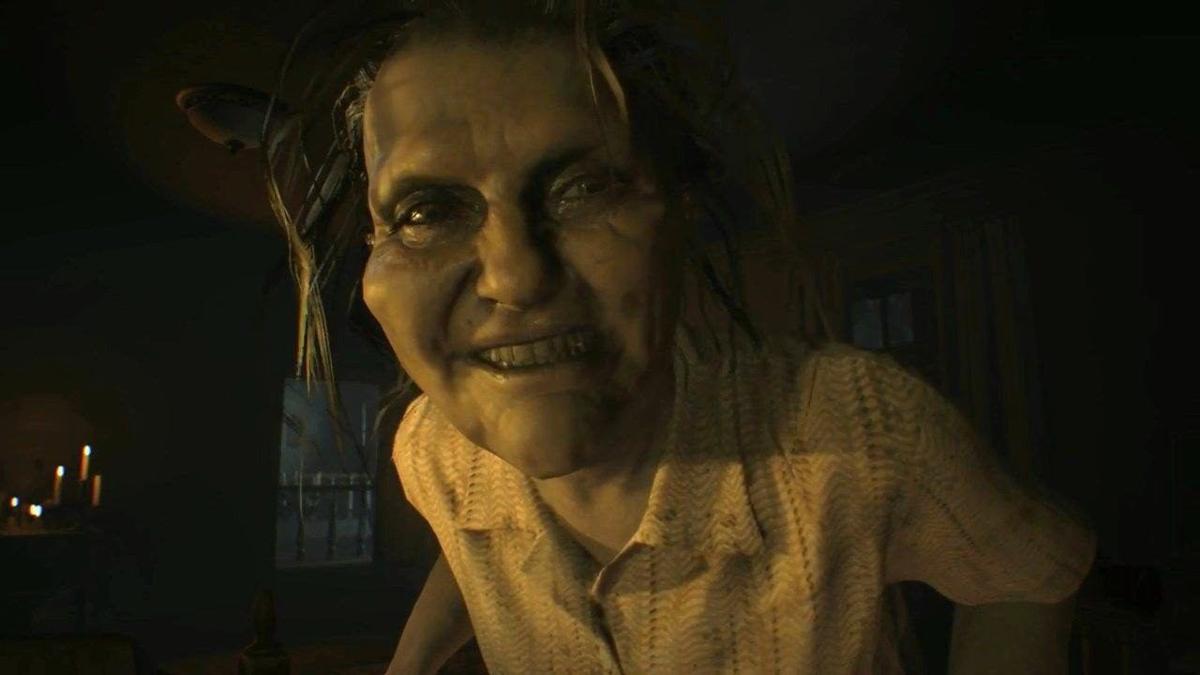

It’s fitting that your boss encounter for this section is Marguerite Baker, a mother whose obsession with children reflects a corrupted maternal instinct. Her desire to destroy Ethan is explained as an overprotective mother taken to her logical extreme.

Marguerite herself is a twisted nightmare version of a mother, part witch and part insect queen. She attacks you by vomiting bugs that quickly swarm you, and as she’s injured, her abdomen becomes a hive that houses more bugs. Marguerite loves her surrogate children, mindless drones that conform to the social hierarchy, but shuns her own biological daughter for rebelling by trying to remain human.

Inevitably, Zoe’s desire for freedom and independence is tied to the destruction of her own family. She sics Ethan on her parents just to survive. She was always the black sheep, an outsider even before everything went to hell. In the wake of her family’s contamination, all she can do is watch them further degrade and wait for you to put them down. She observes your progress and calls each time you defeat one her family members.

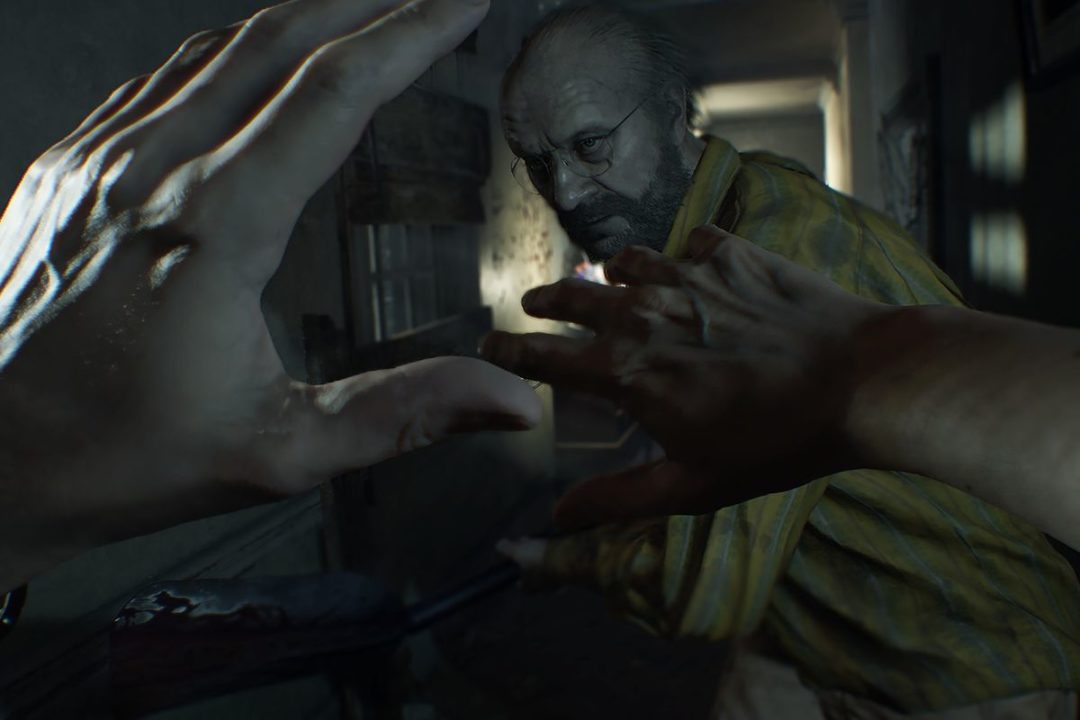

After you deal with her father, Jack, she asks you “Did my daddy give you a hard time?” When Ethan asks her if that’s really her dad, she just replies “He used to be.” It’s just one of many reminders of the people the Bakers used to be, and maybe still are deep inside. You’ll find bobbleheads and helmets hinting at Jack’s love of football, pictures of his military service, and a journal from before his descent to madness. He seems responsible, resourceful, altruistic, and even dorky. Compare that to a note he wrote more recently: “Move that piece-of-shit hippy we caught from the hall to the processing area.”

It all serves to make you sympathize with the people trying to kill you. Marguerite herself shouts at Mia for conspiring with Zoe to bring Ethan to the Baker estate. “What have I done to deserve this except open my home and feed you?” Slowly, we begin to realize that there’s more to this story than a hillbilly murder family that is holding Mia captive.

When Mia’s lie is finally revealed, it recontextualizes who the victims are in this story. We learn that Mia is an operative for a pharmaceutical corporation focused on developing a bioweapon that takes the form of the malevolent child Eveline, who uses a special mold to infect a host’s brain and control them psychologically. Mia’s failure to control and contain Eveline incited the events of Resident Evil 7, including the warping of the Baker family’s minds.

Though Mia is initially perceived as a victim, she was culpable for the disaster. While the Bakers function as our antagonists, their only conscious decision was to take in Mia and Eveline, two strangers stranded after a hurricane. The tragedy of our story is that there is no ideal way to navigate this hierarchy of victimhood without the destruction of at least one family and a child.

After finally saving Zoe and Mia from the last of the Bakers, you’re forced to choose which person to cure with your only remaining serum. Morally and ethically, it’s an impossible choice. Zoe is the sole reason for your success thus far, providing you with information and direction. She’s done nothing wrong. Mia is a liar who helped cause the downfall of the Bakers. But she’s your wife. In choosing to cure Mia, you damn the last of Baker family. By choosing Zoe, you forsake your own.

With the Baker family dead or MIA, the story turns its attention to Eveline, the root of all this corruption. It’s easy to interpret Eveline as just a lazy use of the “spooky little girl” trope. After all, she’s a petulant, sociopathic child trying to force everyone to do what she tells them to under threat of violence. Eveline oozes black mold, and when she gets angry, the force of her emotions renders trees skeletal, fish rotten and bloated, and conjures mold monsters. Visually, her evil corrupts and destroys anything she touches.

And yet, Eveline is also a victim in this story. She’s a neglected child viewed not as a dependent but a weapon, a tool to be used by faceless organizations to convert enemy combatants into willing servants . Eveline gives the evil corporation’s experiments a human face, a tangible example of science not bound by ethics or empathy. In a secret document you find just before the end of the game, you learn that she uses family as the theme of her mind control, ostensibly because convincing strangers to do your bidding is most effective when they think you’re their kid or sister. One scientist posits that someone sentimental might interpret her actions as a lonely kid trying to make up for a lifetime spent in an impersonal lab.

No longer content to be an experiment in a sterile and unfeeling lab, Eveline acts out of anger. She escapes and attempts to create her own family to make up for emotional neglect. After indoctrinating the Bakers, she wasn’t content with just parents and two siblings. She ordered her new family to kidnap more victims for adoption, mostly tourists, drifters, and the homeless. Even though Evie and the Bakers turned countless victims into territorial mold monsters, they still kept a list of each of their names. Why? Because the Molded aren’t faceless pawns. Each of the game’s monsters is an individual conscripted into Evie’s family.

It’s hard not to feel pity for Evie. She lacks the framework to understand healthy relationships. She’s simply a latchkey kid given the power to enact every selfish, wounded desire. When Ethan crafts a necrotoxin capable of defeating Eveline, the game does not allow you an immediate moment of triumph. After stabbing Eveline with the syringe, black tears stream down her face, and she simply asks “Why does everyone hate me?” You’re left to stare at her frail body as she quietly sobs before turning into a completely unrecognizable monster in its death throes. “Goodbye, Eveline,” is all Ethan can manage.

Resident Evil 7’s hyperfixation on family as a theme and source of anxiety makes it more versatile than a purely scary game. While it might not be the scariest game ever made, its strength lies in its ability to discomfit and upset the player in ways that are all too familiar. It’s a grounded story about literal and metaphorical broken homes.

This empathy acts as a catalyst for our anguish, and increases our investment as players. When Jack Baker reappears to Ethan to apologize on behalf of his family, you can’t help but feel moved. In front of you is a man you thought was an abusive, backwoods cannibal. Now he’s been recharacterized as a quiet, generous man who doesn’t want you to blame his family for what’s happened, or even judge Evie too harshly. It’s just a fucked up situation.