Capcom didn’t need to make Mega Man 11. Even if it’s very good — and it is — it doesn’t have to exist. More than 30 years after the original game brought the little blinking blue dude and his weird robot world to NES, the series has done its work. The 8-bit game series reoriented video game action around freedom of choice: make progress however you like from a selection of stages. Mega Man’s ability to adopt the sweet skills of his enemies — blow up a dude with scissors on his head, now you can use scissors, etc. — made him the ideal vessel for genre experimentation. There was blistering anime drama in Mega Man X, 3D role-playing in Legends and trading card strategy in Battle Network. Mega Man even led the charge in deconstructionist, post-modern game design. There’s no big business 8-bit-style indie boom without 2008’s throwback Mega Man 9.

The fight for everlasting peace has been fought on every possible front. Why make Mega Man 11 and why do it now? What could a new game in the original series do besides shatter the Decalogue-esque cleanliness of the games that preceded it? While playing the game, digging into its patient, considered stages and swank cartoon art, it hit me: Mega Man 11 exists because someone genuinely wanted to make it. That passion has yielded an excellent game that justifies the series’ resurrection. Mega Man still matters as long as you can still make a great game with him that doesn’t feel like a cynical retread, and Mega Man 11 is anything but cynical.

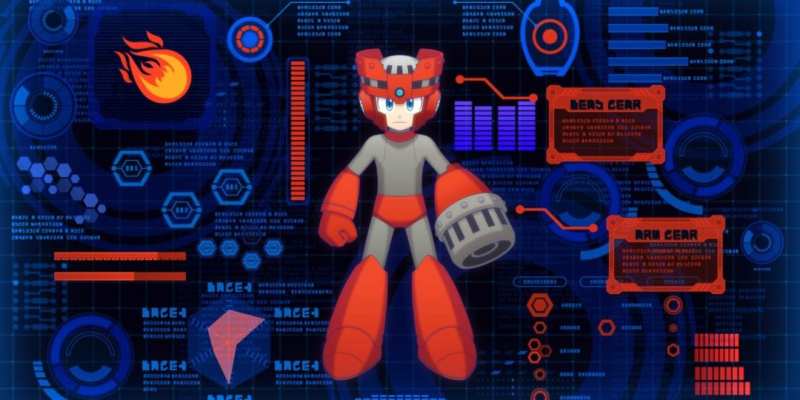

On the surface, everything in Mega Man 11 adheres to the ancient formula. The evil Dr. Wily has a sinister plan to achieve global domination and he’s stolen eight powerful robots built by Dr. Light, forcing them to wreak all kinds of havoc in the year 20XX. Mega Man steps up to blow up some robots and stop Wily’s plan. Retreating from the stripped down, minimalist Mega Man 9 and Mega Man 10, the story ambitions are amped up here with comic book-style flashbacks to Light and Wily’s scientist school days. These stabs at drama add context to the Double Gear System, Mega Man 11’s modest twist on the series’ action formula, but they don’t go so far as to let lore take over. If anything, Mega Man and Dr. Light’s hemming and hawing about not being afraid of immense power as long it’s tempered by responsibility intrude on the good stuff almost enough to be irritating — but not quite. (Even the voice acting is fine. No “Doctah Wahwee” incidents here.) Thankfully, these belabored story beats retreat quickly. There’s a whole lot more bouncing around destroying drones than there is listening to characters drone on.

Sticking with Mega Man 11 reveals the method behind what appears to be mediocre madness.

The hustle through the robot master stages also moves on quickly. At first, Mega Man 11 feels stiff and awkward, its stages simultaneously too empty and too full. This is the first in the series to be developed for widescreen, resulting in a more distant perspective on Mega Man himself and the stages. Block Man’s future-Aztec realm of waterfalls strewn with concrete-crushing gears and Blast Man’s dynamite-laden theme park feel positively lonesome on one screen, with just a couple of enemies dotted around. On the next screen, I felt like I barely had room to breathe with the constant barrage of enemy fire jetting out of floating, big-eyed drones and flying spiked shields.

Sticking with Mega Man 11 reveals the method behind what appears to be mediocre madness. Mega Man’s acquired skills tended to lack versatility in older games. Every robot master is vulnerable to another’s signature weapon, but few of those weapons felt useful outside of those bigger confrontations. Canonized Mega Man games tend to be the ones with rich skill sets that lend themselves to experimentation and improvisation. This is the way that Mega Man 11 truly shines: every new ability in this game feels useful. The initial awkwardness of the spaces you play through comes from their being designed around using as many of those skills as you imagine.

That’s especially true when it comes to the aforementioned Double Gear System. At any given time, clicking the left and right shoulder buttons will either let Mega Man slow down time or make his current weapon extra powerful. Use either skill for too long, and Mega Man will overheat, leaving you vulnerable in particularly hectic moments. Double Gear could have been a gimmick to either make a historically difficult game more accessible or to add unnecessary flash to a game that thrives on simplicity. Instead it’s baked into the flow of every stage. Pushing through the vivid, punishing platforming gauntlets in the end game stages in Dr. Wily’s castle flat out require you to use the time-slowing mechanic. Standard enemies like the little lantern carrying owls in Torch Man’s stage are impossible to crush irritations until you start using the power-up gear and Tundra man’s screen-filling ice attack at the same time. There’s an ideal balance here: Mega Man 11 both subtly tweaks the series’ familiar flow while retaining its essential feeling of grace under pressure.

Once I got into Mega Man 11’s groove, everything else about it started to shine. The more skills you have, the more the extra screen space feels natural. The more stages you visit, the more the primary-colored fantasy robots pop off the screen. The little automatons cluttering up spaces like Torch Man’s robot summer camp pop off the screen, recalling the box art of the NES original Mega Man series. That summer camp itself is classic Mega Man, the sort of illogical but somehow suited to this particular world space that’s made the series so memorable. This time instead of being rendered in the impressionistic palette of pixel art, its brought to expressive cartoon life.

Years back, Capcom tried to make a game like Mega Man 11 work within the series. Developed in just three months, Mega Man 7 for the Super Nintendo tried to take the old 8-bit games and recast them in a slower-paced world with the feel of an animated series. The result was memorably weird but messy. The game opens with an attempt at straight up slapstick humor and ends with Mega Man threatening to murder Dr. Wily. The characters were too big for the screen and the jump-and-shoot play was too awkward. Kazuhiro Tsuchiya, producer on Mega Man 11, was actually a programmer on that game and he’s talked openly about wanting to get back to some of the ideas in Mega Man 7. Director Koji Oda, who’s previously worked on Resident Evil titles amongst others, came to Tsuchiya before Mega Man 11 went into production and said he wanted badly to make a new game in the series. “I want to make this happen,” said Oda.

Their collaboration is beautifully realized, a faithful composition hitting new, pleasurable notes in a song that seemed to have faded out so long ago. Mega Man 11 won’t change video games. It also may not win the series any brand new fans. Nothing is quite so imposing as a double-digit odd number tacked onto a title. Do I have to have played every other Mega Man game to get this? Nope. Curious players recognizing the character from Smash Bros. or one of the multiple cartoons also have plenty of options when it comes to playing the older, more famous games. Mega Man 11 doesn’t have to change video games, though, and it doesn’t have to inspire a new legion of followers. It just has to be as honest and good as it is.

This game was reviewed on Nintendo Switch using code provided by the publisher.