Since Frogwares’ The Sinking City and Cyanide Studios’ Call of Cthulhu demoed at E3 2018, critics have been debating which game would do a better job capturing the feel of H.P. Lovecraft’s horror stories. Having played both I can confirm that The Sinking City is the greater of the Great Old Ones stories, but not by as much as I had hoped.

The Sinking City comes out on June 27, but it was originally scheduled to arrive on March 21. Frogwares said it pushed back the date to avoid a particularly crowded period of new games that included Devil May Cry 5 and Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice, but it’s easy to imagine the studio wanted players to have more time to forget about Call of Cthulhu because of how similar the two games are. Both tell the stories of World War I veterans turned private investigators that are afflicted with disturbing visions and have the psychic ability to reconstruct the past by exploring crime scenes. Both are set in creepy East Coast towns where the residents celebrate their history, don’t take kindly to outsiders, and have too much love for cephalopods.

Your protagonist this time around is Charles Reed, who journeys to Oakmont, Massachusetts looking for answers to the nightmares he otherwise tries to keep at bay by using laudanum. The city has become a beacon for similarly disturbed individuals and in order to get the help he needs, Reed is roped into investigating why the city has both flooded and been gripped by madness.

The investigation portions will be familiar to players of Frogwares’ Sherlock Holmes games. Reed explores scenes of murder and mayhem looking for clues, which he pieces together in a “mind palace” to draw conclusions about what’s happened. Sometimes he must consult archives at the hospital or town newspaper to find a wounded suspect or an ad that will tell you where to go to find further leads. Sometimes you use your special power to see what transpired and have to number the steps that led to one another, though that part feels unnecessary as it’s almost always obvious. It’s still a highly satisfying system considering some pieces of the puzzle won’t connect to anything for hours and figuring out where to go next can require critical thinking not just following basic directions.

As strong as the mystery and plot of The Sinking City are, the game drowns in its open world ambitions.

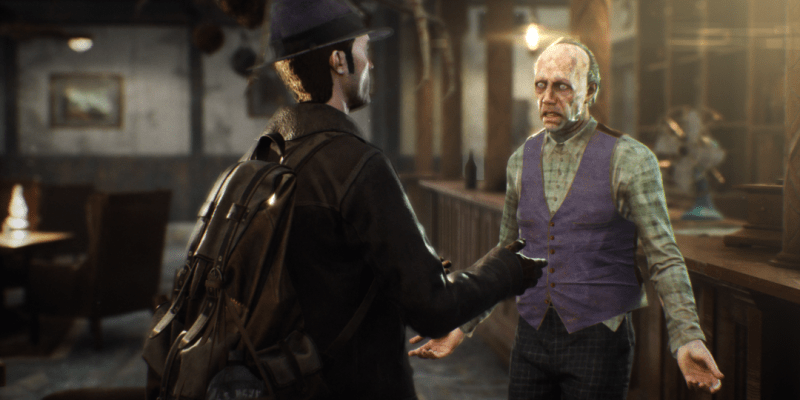

Players are also empowered to lie about their findings. Early on I discovered an Innsmouther, a disturbing looking fish-human hybrid with milky eyes, scales and fanged teeth, had committed a murder under the influence of contagious madness. As creepy as he looked, the man was just a refugee fisherman with a family trying to get by, so I told my client that the murderer had been killed by one of the wandering horrors infesting the city. Like a good noir story, The Sinking City has your troubled hero perpetually searching for the truth, but acknowledges that not everyone is better off knowing it.

The game’s approach to the denizens of Innsmouth also shows a rare acknowledgement of Lovecraft’s white supremacy. Along with an epilepsy warning, Frogwares includes a disclaimer in The Sinking City’s load screens that the game will be tackling issues of prejudice rather than acting like they don’t exist. Turning Lovecraft villains into desperate immigrants discriminated against because they look different and follow a different faith is a clever twist, but it would be more powerful if the Innsmouthers didn’t still have the tendency to kill and kidnap people.

As strong as the mystery and plot of The Sinking City are, the game drowns in its open world ambitions. The sprawling town is navigated on land or with the help of a painfully clunky to steer motorboat when you need to take to water, with fast travel points making it easy to jump between quest objectives once you’ve explored enough. It’s a bleak space, perpetually gray and rainy whether you’re in the grungy dock district filled with rotting fish or the stately homes where the town elders hold court. But there’s not enough that you can actually interact with.

The constantly bustling crowds include men and women in sharp ‘20s attire, shirtless fish men with giant occult tattoos, and people carrying around backpacks obviously filled with human body parts. While Oakmont’s residents will chide you for bumping into them and freak out if you pull out a gun in public, most won’t otherwise talk to you. Even a single line of dialogue from the occult bookseller having a sidewalk sale or the homeless guy actively getting pickpocketed would go a long way to making The Sinking City’s world feel more authentic.

That would also have been a great job for the game’s sidequests. While some of them do lead you through complicated investigations into the city’s high society or criminal underworld, most just send you looking for a specific piece of information in places that have been overwhelmed by monsters dubbed wylebeasts. These Resident Evil rejects include the obligatory fast moving crawly things, kind of stealthed dudes that hit you with ranged attacks, and big fat guys you should probably just run from unless you’re packing heavy artillery. Killing monsters gives you XP that you can spend on talents that make you slightly better at killing more monsters. Gathering materials allows you to craft bullets, traps, and grenades and the biggest caches of components are always in the most dangerous areas.

The Sinking City’s psychological horror is much more powerful than its survival horror, which feels entirely tacked on. With the flood cutting Oakmont off from the outside world, the cash economy has broken down and residents now trade in bullets. The idea of your currency also being your combat resource would be clever if it wasn’t so hard to find anyone who actually wanted to let me exchange my ammo for goods and services. The best that can be said about the boring and pointless combat is that it’s mostly optional and you don’t lose much progress when you die.

Managing side quests is also needlessly annoying. Most missions tell you exactly where you need to visit, but the locations don’t automatically get added to your map. That would be fine for players who want a more authentic detective experience, but the game does offer you the chance to add a location marker. But this must be done manually and then still only shows up if you have the specific quest selected in your log. You also need to have a specific quest highlighted to get useful results for queries when searching an archive, something I only learned after extensive trial since The Sinking City’s tutorial isn’t especially helpful. The side quests should provide a way to stay entertained when you’re stuck trying to figure out the next place to go on the main plot, but I found most of them to be chores rather than entertaining distractions.

There’s a portion of The Sinking City where Reed must don an old timey diving suit to follow in the footsteps of an ill-fated deep sea expedition. While walking across the ocean floor I witnessed a massive cephalopod drifting by. Reed’s declining sanity bar let me know that it was hurting him to look at the creature, but it was too beautiful to look away. I had the same response in general to playing The Sinking City. There’s so much wonderful potential in this game that its flaws are all the more maddening. I wished that it had followed Call of Cthulhu in abandoning combat altogether and just used its larger space and considerably more nuanced investigation system to tell a great story. But it seems I’ll have to keep waiting for the perfect Lovecraft game.

This game was played on PC using a code provided by the publisher. The Sinking City is also available on Playstation 4 and Xbox One.