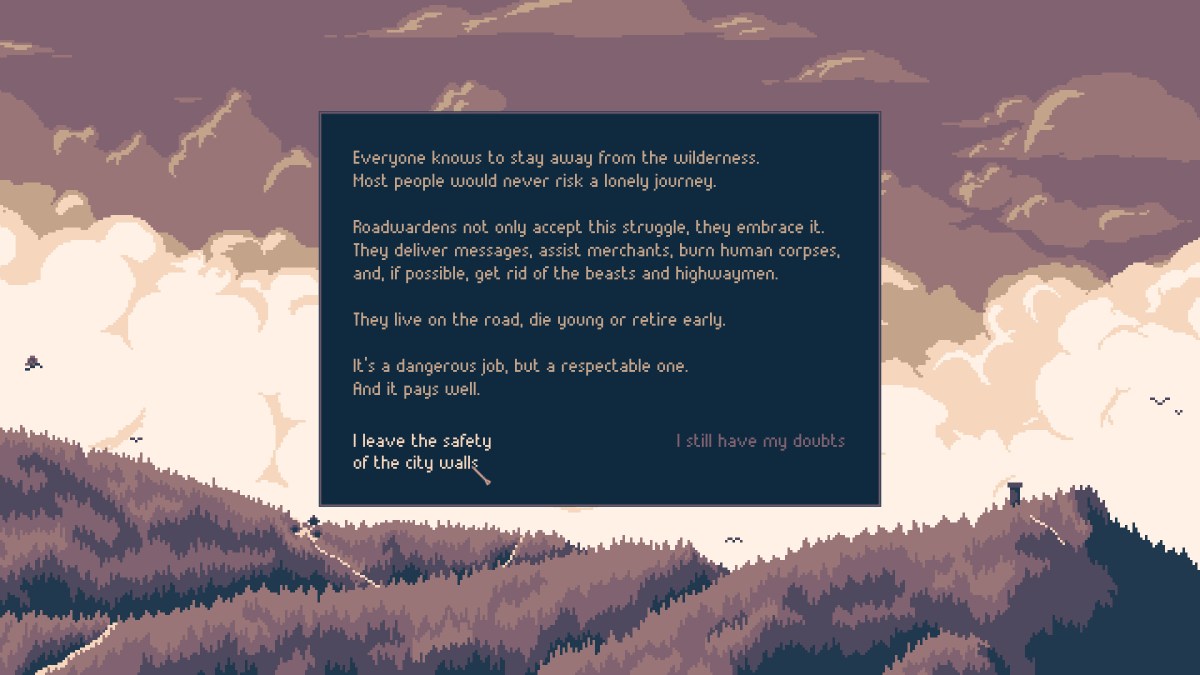

Roadwarden is a bleak game. You arrive on a harsh and hostile peninsula at the behest of your paymasters, the merchant’s guild of a large city, and have just 40 days (more or less, depending on the difficulty level you opt for) to assess the extent to which it may benefit their investment. You follow in the footsteps of the previous roadwarden, Asterion, who the clues suggest may have gone native.

So far, so Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness — a persistent source of inspiration for everything from Apocalypse Now to Far Cry 2. And with good reason: Conrad had a masterful command of prose to paint scenes of captivating beauty and unsettling horror. The parallels are arguably strongest in Roadwarden, given it is essentially an interactive novel enhanced by some evocative pixel art, music, and sound effects.

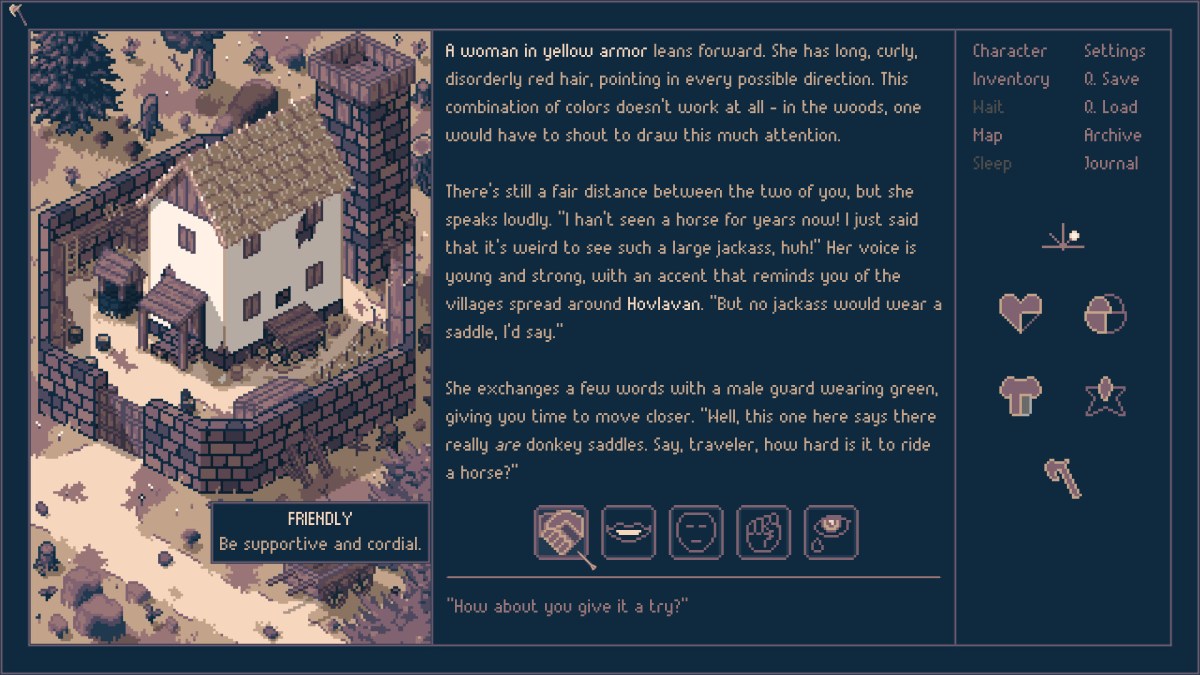

Indeed, the quality of Roadwarden’s prose is its most immediately arresting feature. The world, at least at first blush, doesn’t stretch itself much beyond traditional fantasy tropes. Goblins, harpies, griffons, dragonlings, and many other quintessential mythical beasts roam the wilds. Disheveled villagers and austere druids espouse local knowledge and tenets of their faiths. The undead roam through the fogs, and bandits ply their nefarious trade in the woods. But these tropes are elevated by an elegant prose style that carries an eye for detail, characterization, and world-building without feeling verbose or overly labored.

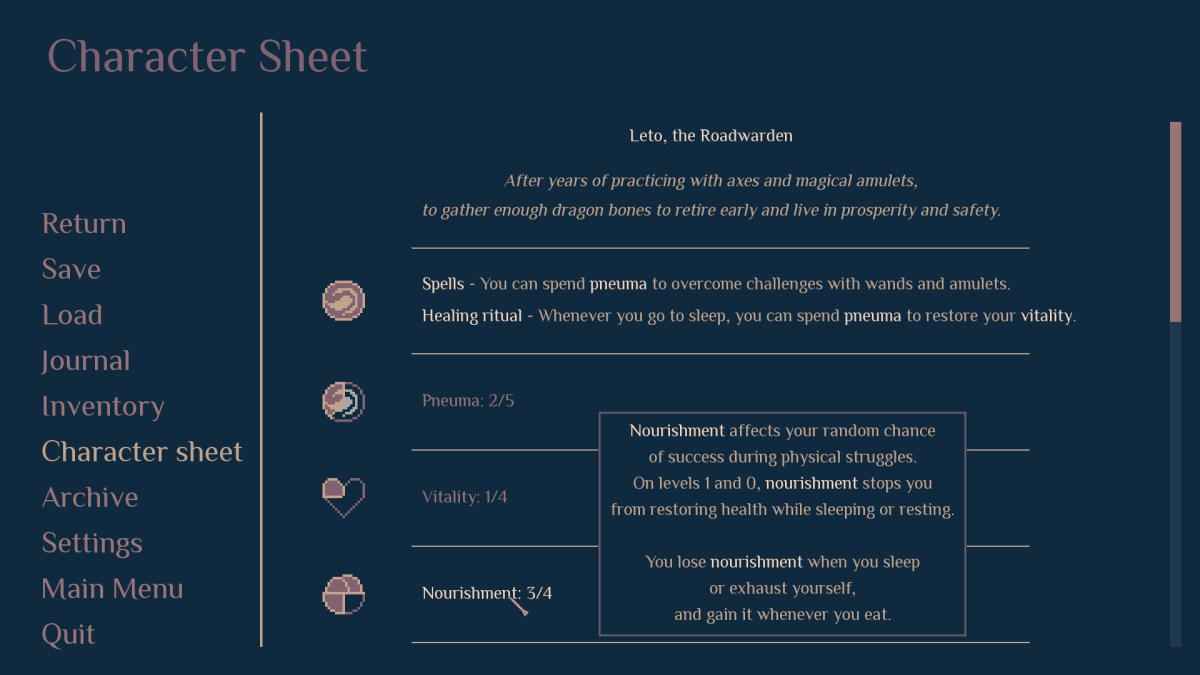

It is only later, as you get to know the peninsula, that you realize things are a little more complex than initial impressions suggest. Many dialogue choices, portrayed as your memories of the past, allow you to define vastly different backgrounds for the city you came from — a kind of retrospective RPG character sheet creation through recollection.

Elsewhere, through lack of means, or the desire to preserve the meager means you earn, you sleep on floors, wash in rivers, eat leftovers, and repair and launder clothes only when absolutely necessary. You take on risky work for low pay; wardening the roads is the perfect opportunity to courier messages and goods, as well as to explore, particularly when your paymasters haven’t provided enough resources for your expedition.

Your austere living arrangements and difficult contracts may bring you closer to the region’s denizens, revealing nuances of local politics, traditions, and geography. One distant village, for instance, is known to most locals but rarely talked about, so it requires an accumulation of local knowledge to ask the right questions, which reveal its existence and location.

If all of that sounds familiar, it may be due to more than just the parallels with Heart of Darkness. Often, Roadwarden feels like a particularly harsh, especially purist take on the The Witcher series of novels. In the books, as in the games and the TV series, Witcher Geralt has friends, lovers, and politicians that he can rely on, but beyond that he finds himself routinely abused, underpaid, injured, tired, dirty, and ultimately alone and ostracized from most communities. Look no further than the series’s ending in The Lady of the Lake, which I won’t spoil here, but which underscores the novels’ theme of the indiscriminate and unceremonious cruelty brought about by xenophobia.

These elements are present in CD Projekt Red’s and Netflix’s interpretations, but they are downplayed compared to in the books. By the end of The Witcher 3’s expansion Blood and Wine, it is possible to settle down to a quiet and relatively prosperous life in a temperate and fertile country. (This ending does echo some of the things Ciri says at the end of The Lady of the Lake, but it’s an uncharacteristically upbeat epilogue to a thoroughly cynical series.)

In contrast, Roadwarden never shies away from its consistently ambiguous choices and grim outcomes. On my playthrough, for instance, I saved a town from a deadly plague and made the Eastern trade routes safer to travel, but I still managed to end my days alone, unloved, and without the influence in the merchant’s guild that I had elected to be my life’s goal at the start of the game. In fact, some poor intriguing within the guild led to my untimely demise.

If Roadwarden manages to feel more like The Witcher than The Witcher games or television, then it’s the roadwarden’s mediocre skill set that most clearly sets the game apart in tone. Geralt may be a loner, but he is a genetically modified superhuman exceptionally skilled at slaying monsters. The roadwarden, by contrast, is nothing special. My fish traps frequently failed, my combat checks often rolled against me, my attempts to persuade got me beaten near to death, and even my alleged education didn’t help me to understand the Old Speech of a secluded tribe.

An amusing piece of optional dialogue with a local child tries to unpack the meaning of “roadwarden” but never manages anything like a precise analysis. Which is just as well, since the roadwarden is not especially good at any one thing — a glorified auditor who is often distinguished only by his horse, a rare sight in the peninsula.

And yet, for all its unflinching bleakness, there is an unlikely coziness to Roadwarden. As you explore the peninsula, the map takes the shape of a closed loop that you grow very familiar with over your 40 game days. Your job means that you traverse it over and over again, and so it becomes second nature to choose where to safely forage and fish, where to stay the night, and how far to push it before needing to find shelter before the deadly dusk. However, as you grow to know and understand the region, that loop also takes on new meanings. Landmarks gain significance, mysterious locations give up their secrets, shortcuts appear, and ultimately new routes grow like offshoots from that core loop.

It’s a pattern of gradual and incremental exploration that I think many of us are familiar with from our childhoods, from visiting and revisiting parks, family homes, recurring holiday destinations, or whatever else. When I was little, for instance, my grandparents had a dacha (a type of land allotment) outside the city. I used to spend my summers there, often cycling a loop that took me through the small village where the dacha was based, across a field towards a forest, over a major road into another village, past a lake, and back towards the dacha. I remember when that route seemed threatening — impassable without an adult or at least a friend to share the adventure.

As I grew up, the route seemed to shrink, to become comfortable and familiar. I started to go out into the forest, deeper into the neighboring village, or along the main road; the route grew and spawned offshoots. But at the end of each summer, before the autumn cold and rain, I returned to the city.

In this sense, Roadwarden also subtly taps into some of our primordial instincts and earliest memories. Its grim sense of place is anchored to a map and a gameplay mechanic that evokes a nostalgic sense of warmth — a subtle and strangely addicting counterbalance to its difficult choices.