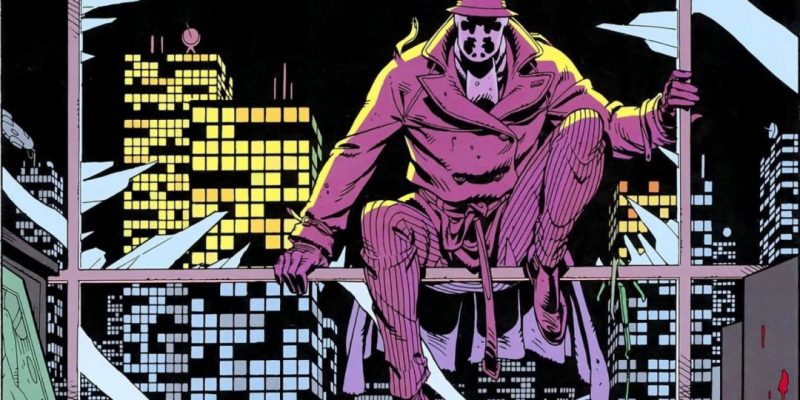

The trailer for HBO’s upcoming Watchmen TV series shows a bunch of vigilante’s with Rorschach-inspired masks chanting ominously. The teaser doesn’t provide much information, but giving Rorschach and his legacy an important place in a new version of Watchmen seems like a good choice. The character was, after all, the moral center of Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ original 1986-87 graphic novel.

Calling Rorschach the moral center of the book may sound dubious. Rorschach in the original comic is a mentally ill, ultraviolent right wing vigilante thug. In one memorable scene he tortures a bystander just because he happened to speak out of turn. Moore has explained in no uncertain terms that Rorschach is not a model to emulate.

“So, I thought, ‘Alright, if there was a Batman in the real world, he probably would be a bit mental,’” the writer said. “He wouldn’t have time for a girlfriend, friends, a social life, because he’d just be driven by getting revenge against criminals… dressed up as a bat for some reason. He probably wouldn’t be very careful about his personal hygiene. He’d probably smell.”

Rorschach is violent, gross, and obviously disturbed. But that hasn’t stopped him from gaining a large fandom. His mask shows black and white blobs, which shift and move but never mix. That supposed moral clarity, in which good is good and evil is evil and there is no grey area between them, has appealed to many readers including Texas Republican senator Ted Cruz. In the comic, Rorschach kills people in inventive and imaginative ways, which makes him seem cool and exciting. He uses household products to fight police like some sort of twisted MacGyver, and expressionlessly drowns a crime boss in the toilet. Moore said he’s disturbed by how many people have identified with the character.

“I had forgotten that actually to a lot of comic fans smelling, not having a girlfriend — these are actually kind of heroic,” Moore said. “So actually, sort of, Rorschach became the most popular character in Watchmen. I meant him to be a bad example, but I have people come up to me in the street saying, ‘I am Rorschach! That is my story!’ And I’ll be thinking, ‘Yeah, great, can you just keep away from me and never come anywhere near me again for as long as I live?’”

The thing that Moore doesn’t say, though, is that Rorschach himself shares many of his creator’s reservations. Rorschach ends up rejecting Rorschach — which is why he ends up being at least a partially sympathetic figure, and a moral one.

At the beginning of the comic, Rorschach writes a passage in his diary which sums up his hatred of moral compromise and his unflinching judgment of basically everyone.

“This city is afraid of me… I have seen its true face. The streets are extended gutters and the gutters are full of blood and when the drains finally scab over, all the vermin will drown. The accumulated filth of all their sex and murder will foam up about their waists and all the whores and politicians will look up and shout ‘Save us!’… and I’ll look down and whisper ‘No.’”

Sometimes Rorschach does behave in accordance with this abhorrent code. He kills and tortures people he thinks are in the wrong with impunity. But there are also moments when he wavers. He decides not to kill his landlady, who badmouthed him to the police after his incarceration, because her frightened child reminds him of his own impoverished, abusive childhood. At the end of the series, when the city does look up and shout, “Save us!” his reaction is not the indifference he promised.

Watchmen famously concludes with superhero Ozymandias aka Adrian Veidt faking an alien invasion by teleporting a monstrous artificial corpse into New York, resulting in the death of millions. He does this because he believes that an alien threat will united the world and prevent a nuclear conflict between the U.S. and Russia. Ozymandias’ plan seems to work; there’s international sympathy for American victims, and world leaders pull back from the brink of war.

Only a few other heroes know that Ozymandias is behind the plot, and they agree not to reveal the truth in order to preserve the fragile peace. But Rorschach refuses to go along with the whitewash. He insists on trying to bring Ozymandias to justice by telling the world what he did. “Not even in the face of Armageddon,” he says. “Never compromise.”

This is consistent with Rorschach’s black and white morality. Ozymandias has done wrong, and Rorschach must punish him. But Rorschach’s reaction is also a rejection of his own apocalyptic fantasies. He claims he longs for the moment when New York is judged and found wanting and the sewers run with blood. But when the sewers actually run with blood, he’s horrified. He weeps. He tries to help.

Rorschach intends to tramp back to civilization to expose Ozymandias’ culpability, but the nuclear-powered Dr. Manhattan confronts him before he gets that far. Knowing he’s about to die, Rorshach takes off the he often refers to as his face.

This is a significant statement about identity for Rorschach. The hero had a mental break following a brutal kidnapping case where the perpetrator fed a kidnapped child to his dogs. He decided that his true identity was Rorschach, not his original self, Walter Kovacs. By removing his mask at the end, Rorschach stops being a vigilante and becomes just a guy.

Kovacs, like Watchmen‘s readers, decided that Rorschach was his favorite character; he too thought “I am Rorschach!” But in the end he rejects that identity the same way Moore does. He dies as Kovacs — an everyday schmo whose bones will build the foundation of some vaunted superhero’s utopia.

Rorschach says he wants a genocide, but he balks at genocide denial. He says he’s a superhero, but when he’s forced to choose between standing with the powerful or dying with victims, he chooses to be with the victims he claims to hate. Rorschach is Watchmen‘s most sympathetic character because he finally decides that he is just as tired of stories about the powerful and their super violence as Moore was.