I sit down to dive back into Season: A Letter to the Future, and a profound sense of calm washes over me. It’s like the meditation that comes at the end of a yoga session. I am present. I am here. Except “here” is a digital space. Video games are a media of oppositions, and the split sense of the player-character is one of the most potent. As critics, we use words like “immersive” to describe the feeling of crossing that divide — of becoming less player and more character. I’ve used that word myself to describe experiences like Gone Home and Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice, but it’s rarely felt quite as true, quite as accurate as it does for Season.

A significant part of the reason for that is that Season: A Letter to the Future has a different relationship to the senses than many other games.

It’s all about tactility.

As students delving into creative writing for school assessments, one of the first things we’re taught is to stimulate the senses; readers should feel a part of the story. We’re challenged to describe not just what is seen and heard but also what is felt, tasted, and smelled. Though among the most basic advice to budding writers, it’s a wellspring to unlock the richness of a story.

I recently read a short story, “First Man” by Mjke Wood, that uses touch to great effect. From the initial description of the landing (“a kiss and a roll”) to the way touch becomes necessary for guidance, it’s an excellent example of how the senses beyond sight and sound can help to ground the reader in the experience.

Likewise, in The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, Gimli’s reaction on first trying the baked good lembas in Lórien makes clear the taste. “Gimli took up one of the cakes and looked at it with a doubtful eye.” Then “he broke off a crisp corner and nibbled at it. His expression quickly changed, and he ate all the rest of the cake with relish.” Soon after, he describes it as “better than the honey-cakes of the Beornings, and that is great praise, for the Beornings are the best bakers that I know of.”

Books are littered with such small observations.

Increasingly, games are too.

In A Plague Tale: Requiem, Amicia will gag when coming across fly-blown corpses. In Death Stranding, the balance mechanic makes sure you’re aware of undulations and variations in the ground in a very tactile way.

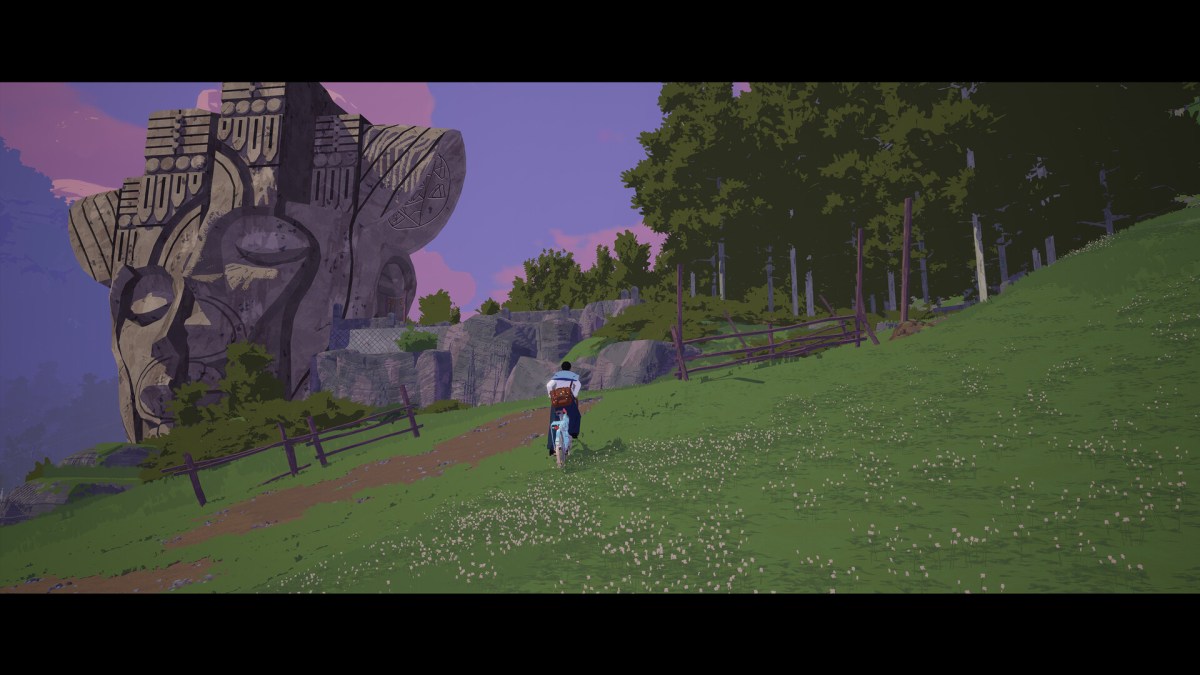

In Season: A Letter to the Future, you’re a documentarian. You’re on a mission to record — and hopefully understand — how and why the current season of the world is ending and what it will mean. Your methods of doing so are relatively familiar: photos, audio recordings, sketches, and the collection of artifacts.

Functionally, then, Season isn’t doing anything new. Games from Umurangi Generation to Draugen to Sherlock Holmes Chapter One and far beyond have used variations on these core ideas. What sets Season apart is the purpose of these mechanics. You’re not solving a crime or completing photo bounties; you are simply observing the world around you to sate your own curiosity. This approach means your attentiveness is entirely at your own discretion.

This focus on being aware of the world positions Season as a fascinating contrast to the recently released Hi-Fi Rush. Tango Gameworks’ rhythm-action throwback likewise rewards the player for paying attention to the world around them, but in a different way. The mise en scène pulses with a persistent musical beat, and timing button presses with that deals more damage. It brings your touch in line with the visuals and audio of the game world. In theory, it should have a very similar effect to Season. Except it doesn’t.

The difference lies in how the two games approach that unification of the senses. Hi-Fi Rush centers you. The rhythmic movements of the world support your play. Paradoxically, this reduces everything to either a metronome or something to hit. It prioritizes pleasure over experience. That’s fine, but Season is much more interesting in its dedication to do exactly the opposite. It decenters you.

And it’s like diving into a pool of sensations.

The evocation of the senses comes before the beginning of your journey, during the story’s exposition. Before you set off, your mother insists on creating a protective pendant. Doing so requires the sacrifice of objects that connect to the character’s senses. You rifle through the small house for suitable items, and the descriptions follow: words like “cold” and “bitter” and “smooth” alongside hints of memory. Once you find the thing you think best reflects the sensation — perhaps a candle for smell or an old sketch of your father for sight — you hand it to your mother. In surrendering the item to the burner, she also gives up a memory that’s attached to that thing.

This commingling of sense, memory, self, and experience paves the way for the remainder of the game to weave its magic. It prepares you to be aware of your surroundings, to feel that you exist as an embodied, embedded piece of this world.

And then it casts you free.

The journey begins in a winding street of Caro Village, high in the mountains. Music plays somewhere nearby. A minimalist UI lets you know you have a camera and a recorder and that’s about it. There is space, and there is silence.

As you follow the path, you unlock the world. A music player. A fountain. A vast, sprawling tree. Murals. The remnants of a party. It’s up to you if you want to record these vestiges of a particular time and place. If you do so, the player character will describe a piece of lore or an observation or maybe raise a question. Before that can happen, you have to make the conscious effort to document the world around you.

Season: A Letter to the Future asks you not just to look, but to see. Not just to hear, but to listen. Not just to touch the controller in your hands, but to feel the things you tuck away in the scrapbook. The game stimulates the senses by simulating what it can and allowing you the time and freedom to fill in the gaps left behind.

Game developers are getting extremely good at creating stunning worlds, but they’re rarely as good at making those worlds feel tangible. That may be because, like in Hi-Fi Rush, they’re about giving the player a rollicking good time. Or it may be because, like in Forspoken, the fun is in moving through the world at speed. Or it may be because, like in Elden Ring, you’re constantly attuned to the presence of danger.

By stripping things back like the walking sims of yore, Season does away with all of that noise. It fills the gap with things. A lot of those things don’t matter. Except maybe because you can document them anyway, they actually do. This world isn’t a playground and it’s not a plaything. It’s something that seems to exist whether you’re present or not. And that makes it a sheer delight to visit.