Prequels are not a new phenomenon. There are plenty of historical examples, including The Good, the Bad and the Ugly from 1966 and Butch and Sundance: The Early Days from 1979. However, these projects were rare enough that critics were arguing about the proper term for them into the new millennium. In May 1984, Vincent Canby described Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom as a “pre-sequel.” In June 2003, Dave Kehr optimistically dismissed the word “prequel” as “an already antique neologism.”

Prequels are tough. They present a unique set of challenges for storytellers, in that they are built around stories where the audience already knows the end. There are logistical challenges that come from trying to line up a story with preexisting constraints. There is also often a sense that the audience has already seen the most important story featuring these characters. To quote Vince Gilligan, the co-creator of Breaking Bad prequel Better Call Saul, “prequels are really damned hard to write.”

Of course, there are a handful of good prequels. The recent Planet of the Apes trilogy occupies a strange space between prequel and reboot for the science fiction franchise, but it crafted an epic story that offered an insightful commentary on the world around it. Although it was dismissed on its premiere at Cannes, David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me has been reclaimed as a cinematic masterpiece. Still, most cinematic prequels tend to be forgettable, at best.

So it is interesting that this year’s slate of high-profile television has been dominated by prequels. Better Call Saul wrapped up an incredible final season. House of the Dragon took viewers almost two centuries back into the history of Game of Thrones. Amazon decided that the most expensive television show ever made should be a (very) distant prequel to The Lord of the Rings. Andor will be a prequel to Rogue One, itself a prequel to the original Star Wars.

Of course, these are parts of a larger trend. The Star Trek franchise has been preoccupied with prequels since the end of Voyager, with shows like Enterprise, Discovery, and Strange New Worlds all launching as prequels to the original Star Trek. Both Gotham and Alfred are stories set within the Batman mythos before Bruce Wayne becomes Batman. All the Star Wars shows are prequels of some sort or another, sitting in the negative space between the three trilogies.

As such, this obsession with television prequels didn’t emerge from nowhere. It is arguably an acceleration of a larger cultural movement, the culmination of this preoccupation with stories about the “before” times for audiences’ favorite stories. In some ways, it’s just another face of the nostalgic hydra that has nestled close to the heart of contemporary culture, a companion to those overly reverential sequels or those superheroes endlessly recycling familiar brands.

Still, there is something uniquely challenging about television prequels. These are not simply two-hour-long unseen adventures built around recognizable characters. These are extended multi-year narratives building to a setup that has already been well explored. J.D. Payne and Patrick McKay have boasted of a five-year plan for The Rings of Power. HBO reportedly plans to run House of the Dragon for “about three or four seasons.” Andor was planned for five seasons, then three, then two.

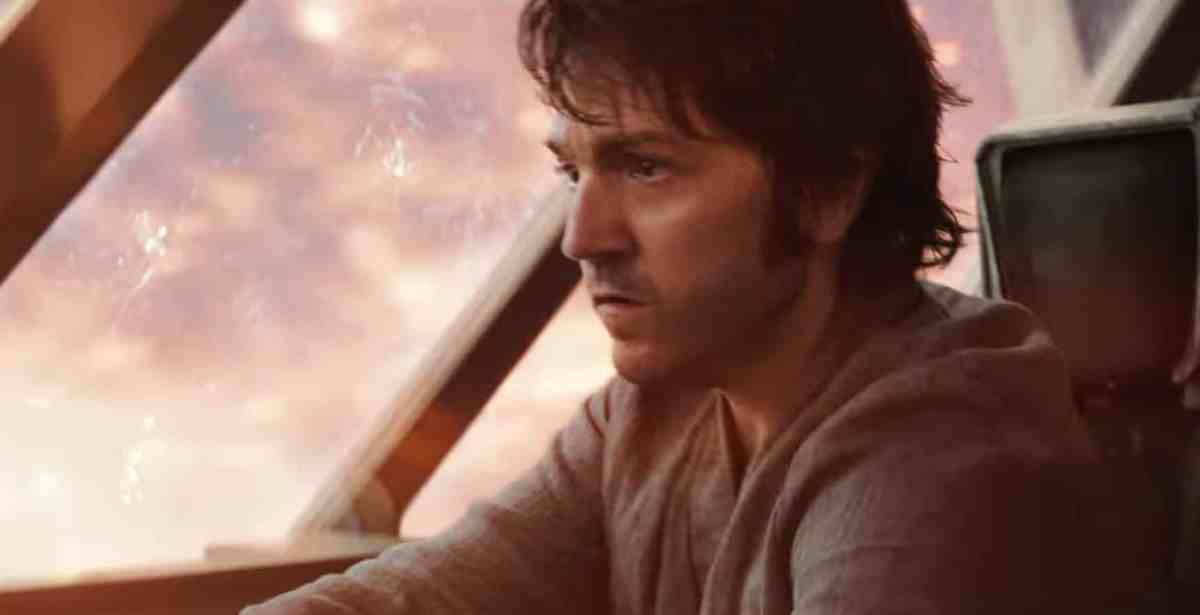

These shows are effectively asking audiences to invest hours upon hours of their time over years of their lives into stories to which they already know the ending. Cassian Andor (Diego Luna) dies in Rogue One. House Targaryen is toppled more than a decade before Game of Thrones, its heirs sent into exile. Galadriel (Morfydd Clark) cannot defeat Sauron in The Rings of Power because the Dark Lord will only be properly vanquished at the end of The Lord of the Rings.

However, audiences and critics don’t seem particularly bothered by any of this. House of the Dragon has continued to grow its audience across its first season, and HBO was satisfied enough to commission a second season immediately after the figures came in for the premiere. Amazon reports that 25 million people watched the Rings of Power premiere. Critics have argued that Better Call Saul is better than the show from which it was launched. Early reactions to Andor border on ecstatic.

There are a number of interesting things to parse about all this. Most obviously, it seems to put to bed any serious debate about the importance of spoilers as a driving force of audience engagement. Audiences know how these stories will end, and that knowledge does not ruin the experience for them. There has been plenty of evidence supporting this observation in the past, but it is baked into the popularity of these shows. However, it may also be something more fundamental.

These shows can generate tension and suspense in their specifics. Better Call Saul was phenomenal at escalating the stakes in seemingly small-scale situations, even if viewers knew where the story was going. The Rings of Power is a show obsessed with mystery boxes, designed with the intention of keeping viewers hooked. Audience members who haven’t read Fire & Blood have no idea how Rhaenyra’s (Milly Alcock, Emma D’Arcy) battle for the throne will play out in House of the Dragon.

However, underpinning these small-scale mysteries is an appealing certainty. There is a consistency to these prequels. Audiences know what they are getting. The production design on all of the live-action Star Wars shows is similar to the aesthetic of the original Star Wars films. Part of the appeal of Better Call Saul is getting to check on familiar faces in the Albuquerque underworld from Gus Fring (Giancarlo Esposito) to Hector Salamanca (Mark Margolis) to Krazy-8 (Maximino Arciniega).

This is true even of those prequels separated by centuries or millennia from their source material. The production design on House of the Dragon is remarkably close to that of Game of Thrones, even though the two shows take place more than a century apart under two different dynasties. The Rings of Power looks and sounds a lot like Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, even though it is set several millennia earlier in the history of Middle-earth. These prequels are built on familiarity.

There is an interesting conservatism at play in the returns to these imaginary worlds through the lens of these prequels. Given that the audience already knows the endpoints of these stories, these prequels offer reassurance that these imaginary worlds will never truly change. Sure, the White Walkers might threaten Westeros in Game of Thrones and Sauron might lay siege to Middle-earth in The Lord of the Rings, but in the centuries and millennia between, those places remain fixed.

In the millennia between The Rings of Power and The Lord of the Rings, Middle-earth will look just like it did during the Peter Jackson movies. In the centuries between House of the Dragon and Game of Thrones, Westeros will be unchanged. The universe depicted before the original Star Wars in Obi-Wan Kenobi and Andor is not so different from that explored after Return of the Jedi in The Mandalorian and The Book of Boba Fett. These spaces aren’t just preserved; they are maintained.

It is easy to understand the appeal of this to audiences. These are deeply uncertain times. The future is ominous, with threats to democracy, the erosion of basic human rights, ongoing financial chaos, and even the looming threat of a climate apocalypse. Parents are pessimistic about the future facing their children. It is easy to understand the appeal of these prequels in that context — extended multi-season shows built around the comforting certainty of a familiar status quo.

Of course, many of these original sagas are about change. These epic stories often end with the destruction of the status quo. To quote Yeats, many of these worlds are “changed, changed utterly” in the telling of these original stories. Game of Thrones is ultimately a story about the folly of the fantasy feudal setting the show depicts. The Lord of the Rings is a nostalgic text, but built into that nostalgia is an understanding that its magical world is already fading into myth and memory.

These sorts of prequels allow audiences to avoid dealing with the uncertainty that might follow such universe-shattering conclusions. If the ending of a prequel series is already written, and if it is knowable, then it offers an alternative to the turbulence of the real world. The first-season finale of Strange New Worlds is built around the idea that the existing timeline must be preserved at all costs, including the tragic ending of Captain Christopher Pike (Anson Mount).

This gets at a noteworthy detail: Most of these stories end in tragedy. In Better Call Saul, Jimmy McGill (Bob Odenkirk) will end up hiding from the law in Nebraska. Cassian Andor will lead a suicide mission to infiltrate Scarif, where he will be consumed by a blast from the Death Star. Sauron will survive the events of The Rings of Power and wage a destructive war. The Targaryen Dynasty will end with Daenerys Targaryen (Emilia Clarke) turning King’s Landing to cinders.

There is a grim implication to all of this. Over the multiple seasons of these shows, do audiences prefer a grim certainty to ambiguous uncertainty? Is knowing always better than not knowing? This is perhaps what separates Better Call Saul from the other television prequels. In the show’s final stretch, it pushes past the events of Breaking Bad into uncharted narrative territory. Interestingly, it finds some measure of redemption there, as happy an ending as possible.

It is striking that so much modern pop culture is built around multi-year journeys to predetermined destinations, extended television shows that — by their nature — must end in failure for their protagonists. Sometimes it feels like a world without a future.