This article contains major spoilers for Somerville, including for the ending.

While I agree with KC Nwosu’s review that Somerville misses with its big swing into epic sci-fi, the game fares much better with its portrayal of loss. It follows a man’s attempt to reconnect with his family after they are separated during the initial phase of an alien invasion. Where other games or films might fill that space with vivid displays of grief or determination, Somerville takes a pared-back approach.

A large part of what helps Somerville to succeed is the importance placed on the exposition phase of the narrative. The exposition is the part of a story that sets out what is normal. It’s Harry Potter’s abusive living conditions with the Dursleys, the Stranger Things gang’s D&D session, and the introduction to Dolores, Teddy, and the park in Westworld.

It doesn’t take much, yet games often undervalue the long-term impact of that initial scene-setting. That makes sense given the medium’s interactivity, but the exceptions — the likes of Red Dead Redemption 2 and A Plague Tale: Requiem — show that it can be done effectively. Somerville is another stellar example.

Here, though, in the absence of words, director Chris Olsen’s experience in character animation takes center stage. Somerville begins with a domestic scene: a family asleep on the couch in front of a TV showing white noise. The child, a toddler, wakes and sets about getting up to mischief. Eventually you stumble into trouble you can’t get yourself out of. The parents — let’s call them Orpheus and Eurydice — stir and come to your rescue. It’s everyday stuff: comforting the child, tidying up the mess left behind, closing the windows, taking care of the dog. We can connect with the situation because it’s so mundane. It could be your own family.

It’s only once that sense of normal and that sense of connection is established that all hell breaks loose. A mistake in the midst of the chaos leaves Orpheus unconscious. When he wakes, his family is gone. Only the faithful hound remains. That, too, taps into a long-standing trope of storytelling. From I Am Legend to Fallout, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz to Love and Monsters, dogs as companions often stand in as links to the world left behind. So too is that the case here. We don’t know what happened to Eurydice and the child. We don’t even know where Orpheus thinks he’s going. He’s pushing forward but towards what?

Before long, even that connection is lost. To continue on, Orpheus has to drop down a gap too high for the dog to follow. And again, the game doesn’t play up the severance. There’s no fanfare, no pomp or ceremony. The dog simply sits at the edge of the projection and barks as you fade into the distance. The moment reinforces the quiet, desperate grief that underpins the entire journey.

Eventually, Somerville reaches an emotional crescendo. After descending into an underground mine, our hero overcomes a series of challenges and stumbles into a haven. It’s a quiet space where the survivors gather, heal, and pray. For our Orpheus, it’s the beginning of the next phase of his quest.

This is where the retelling of the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice becomes most clear: Orpheus passing through Hades and, in return, earning a chance to reunite with his wife. The condition is that he must lead her out of the underworld without looking back.

Similarly, the hero of Somerville reunites with his family, and together they set forth again. They try to traverse a ruined, overrun city. It is a quest doomed to fail.

Throughout a tense escape sequence, Somerville inverts the myth. Eurydice leads the way as they travel upwards, first along an inclined street, then into the belltower of an old church. Then with a deus ex machina salvation at hand, our Orpheus makes the same error of judgment as the one of legend: He puts himself first.

In the myth, Orpheus looks back just as he crosses the threshold, forgetting that both of them had to be in the land of the living for the deal to hold. Here, he steps first into safety. In both, Eurydice pays the price.

This moment hits all the harder because you don’t expect it. The reunion is a symbol of hope. If Orpheus can find his family miles across the countryside when things are so dangerous, then maybe they really will be able to find a sanctuary elsewhere. Plus, dei ex machina usually serve to fix things. The alien warrior who fights for your safety and the spacecraft that descends from the heavens are promises that everything will be alright — a promise that’s broken almost as soon as it’s made.

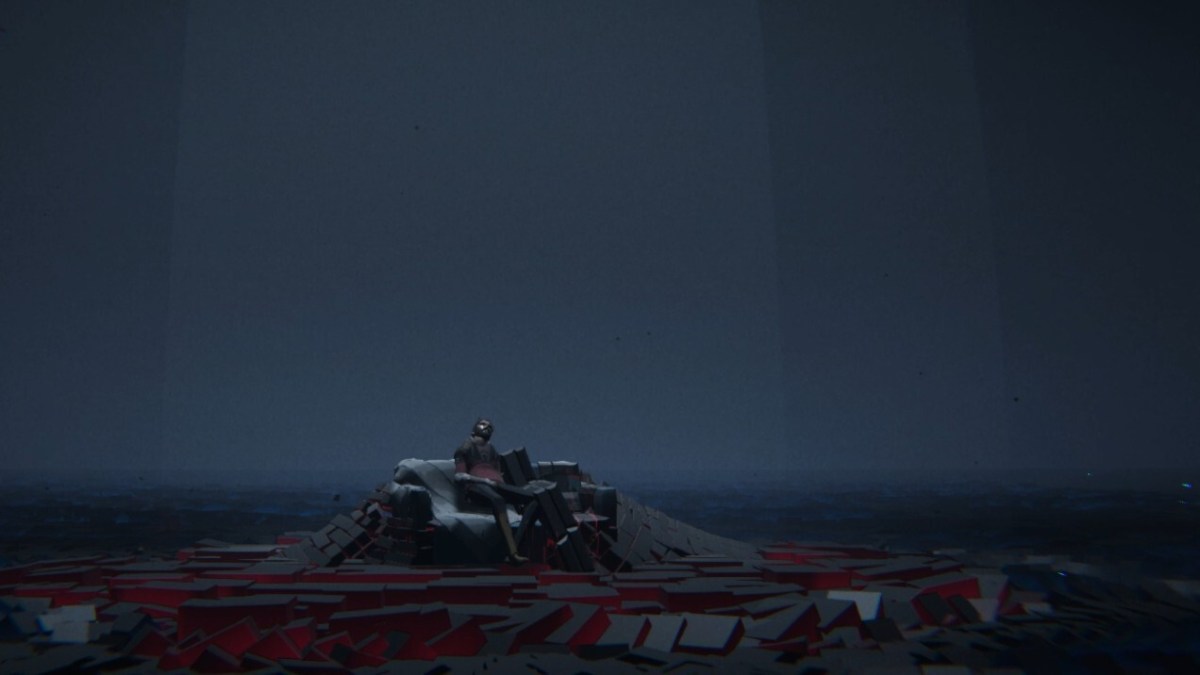

From there, Somerville embarks on a final act of sci-fi psychedelia that, nevertheless, never forgets what drives Orpheus. He relives the highlights of the journey already taken. In doing so, he comes across several instances of Eurydice and the child sitting on the couch from the beginning. There are no words or actions needed. The image speaks for itself. In the wake of the losses already, it’s a tempting proposal to sit down, even for a moment, and try to hold on to the past. You can choose to give up.

If you do so, the game taunts you with a fade to black and Orpheus alone in an empty world. You can’t hold on to Eurydice. Instead, if you want to see how the story ends, you have to activate your powers and melt the idol of her. It’s an act of betrayal that sets up the conclusion.

Past those memories, you finally confront the invaders. But they are not done playing with you. There’s a form of communication, and then Orpheus’ house rises from the ground. If you move towards it, light spills out as the front door swings open, and Eurydice emerges.

You know it’s not real. You know it’s a trick. But you have the choice between being a hero and being a human. That conflict sits at the heart of Somerville, and the game makes you feel that it’s a genuine conflict. The world has fallen apart, but so has everything Orpheus cares about. His hope and his purpose have been stripped away — and stripped away all the more forcefully because he was so close to holding on to them. The question you’re left with is whether or not that suffering is enough to make you give up on everything.

The success of Somerville lies within its simplicity. With gestures taking the place of dialogue, there’s no danger of players missing the point because of haphazard voice acting or writing. The callbacks to other stories are guideposts for our emotions because of how cozy and familiar they make it feel. Underpinning all of that is the dedication to a straightforward goal. Through the puzzles and the sci-fi and the horror, Somerville doesn’t for a single moment forget that it wants you to feel something.