This review and discussion contains spoilers for Star Trek: Picard season 3, episode 1, “The Next Generation.”

The issue with the current nostalgia boom isn’t what it remembers. It’s what it forgets.

In its third season premiere, “The Next Generation,” Star Trek: Picard is saturated with throwbacks and references to things that the audience already knows and recognizes. Before any character appears on screen, the audience hears the playback of (then) Captain Jean-Luc Picard’s (Patrick Stewart) log entry from “The Best of Both Worlds.” Before Picard himself appears on screen, the camera lovingly takes in a version of the famous portrait from the Ready Room on the Enterprise-D.

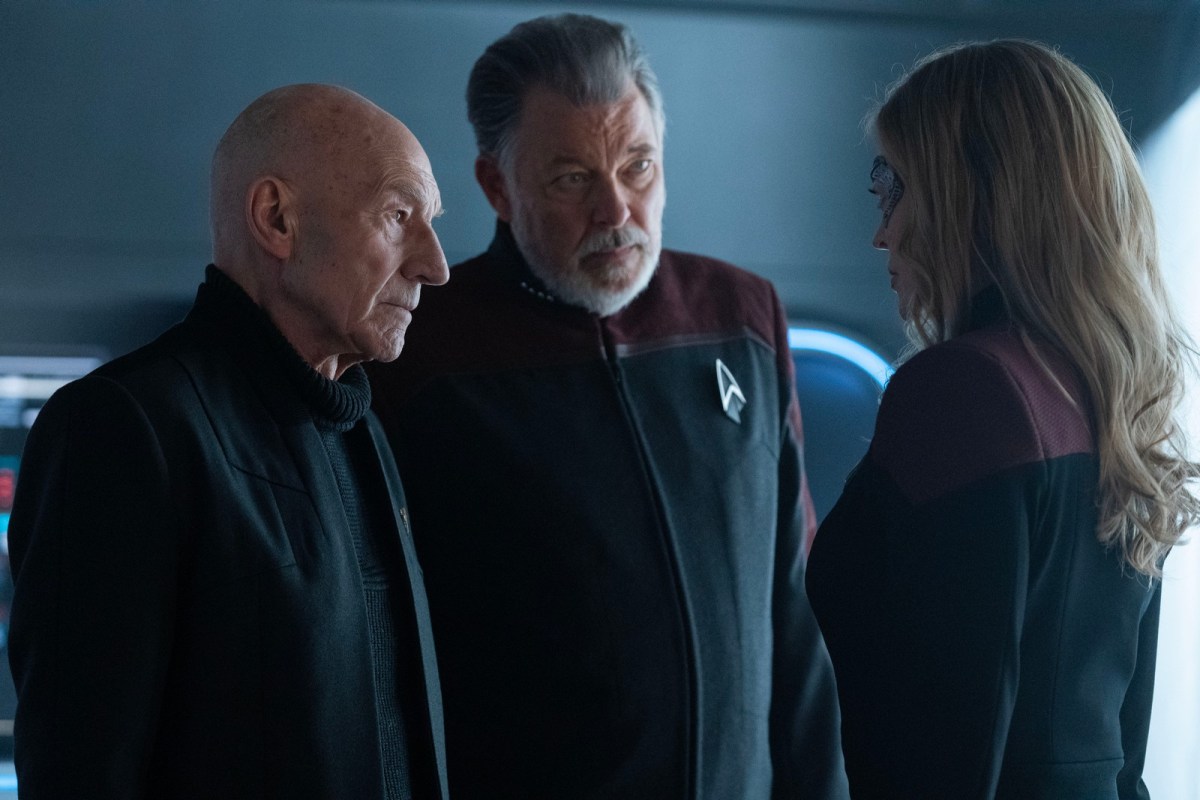

When Picard accompanies Captain William T. Riker (Jonathan Frakes) to inspect the Titan, the sequence is framed as a loving homage to one of the most recognizable sequences from Star Trek: The Motion Picture. It is a nostalgic reference so obvious that Lower Decks affectionately spoofed it in its first season episode “Crisis Point.” When Picard receives a coded message from Beverly Crusher (Gates McFadden), it’s with his comm badge from The Next Generation, not the version from any of the feature films.

“The Next Generation” is saturated with these references. Picard and Riker arrive on the Titan to find the daughter of their colleague Geordi La Forge (LeVar Burton), Sidney (Ashlei Sharpe Chestnut), is serving as navigator. It recalls Generations, where Kirk (William Shatner) and McCoy (DeForest Kelley) arrive on the Enterprise-B to find the daughter of their colleague Hikaru Sulu (George Takei), Demora (Jacqueline Kim), is serving as helmsman.

Even the iconography feels overly familiar. The design of the alien ship menacing the Helios at the end of the episode, and the way that sequence is shot, plays as a less expensive rendering of the confrontation between the Enterprise and the Narada in J.J. Abrams’ Star Trek. There are plenty of Easter eggs, with “the Red Lady” revealed to be a statue of the captain of the Enterprise-C, Rachel Garrett (Tricia O’Neil), from “Yesterday’s Enterprise.”

It all seems calculated to stoke the nostalgia receptors of the audience, to reassure them that they are watching Star Trek, because this is a show populated with items from Star Trek. It looks like Star Trek. It constantly references Star Trek. Closing with Jerry Goldsmith’s end titles theme from First Contact, and liberally peppering familiar Star Trek music into the soundtrack, it even sounds like Star Trek. It must be Star Trek. The show makes a hard sell.

In some ways, it is just as tacky as the branded memorabilia that Guinan (Whoopi Goldberg) is peddling through her bar. “Guinan’s hawking souvenirs now?” Riker asks a bartender (Jeni Wang) in disbelief. It’s a candid moment from the show, one every bit as honest as opening the season to “I Don’t Want to Set the World on Fire” by the Ink Spots, a song boasting about how the narrator has “lost all ambition for worldly acclaim” in favor of wanting to be loved.

The first two seasons of Picard had their problems, but it was to their credit that they were at least trying to be their own thing. There was perhaps a little bit too much nostalgia with the return of characters like Data (Brent Spiner) and Q (John de Lancie), not to mention the second season retreading both The Voyage Home and First Contact, but it had its own distinct voice and vibe. It wasn’t well written, but it was trying to say something unique.

Indeed, early publicity for Picard made a point of stressing that it was not going to be a hollow attempt to resurrect The Next Generation. Co-creator Alex Kurtzman noted Stewart was “uninterested in repeating himself.” By his own admission, Stewart only agreed to the revival when he “was eventually convinced that (he) would not be stepping back into Next Generation.” Picard was obviously a nostalgia play from the outset, but at least the show tried to be different.

Allowing for the myriad problems with the first two seasons of Picard, there is something disheartening in how eagerly the show shed its own distinct identity in a rush to recapture some faint echo of The Next Generation. By the start of its third season, Picard has jettisoned most of its original characters to make room for returning players: Agnes Jurati (Alison Pill), Soji (Isa Briones), Elnor (Evan Evagora), Narek (Harry Treadaway), and Chris Rios (Santiago Cabrera).

With the exception of former Voyager regular Seven of Nine (Jeri Ryan), the only remaining member of the original Picard ensemble is Raffi (Michelle Hurd), and that seems like a choice driven by plot necessity rather than any affection for the character. Recurring guest character Laris (Orla Brady) does pop up in an early scene in “The Next Generation,” but the purpose of that scene is largely to write her out of the show to make room for returning Next Generation cast members.

“The Next Generation” is shameless in this embrace of nostalgia, to the point that one early scene transition occurs by fading from a painting of the Enterprise-D to a collectable souvenir model of the Enterprise-D, a ship that doesn’t exist anymore and was destroyed at the climax of Generations. “First love is always the sweetest, isn’t it?” Laris asks. Picard replies, “Well, she wasn’t the first. But she was certainly my favorite.” If nothing else, “The Next Generation” communicates that clearly.

There are two strange details in all of this nostalgia. The first is how hard “The Next Generation” works to justify this fetishization of the past. The episode is weirdly defensive about its invocation of the past, as if embarrassed at how shameless it is trying to conjure the ghosts of a television show from three decades ago. A surprising amount of “The Next Generation” is dedicated to arguing that this is really a brave and daring creative choice, if one stops to think about it.

“The Next Generation” tries to present its nostalgic fetish objects as underdogs in need of validation and celebration, as if anybody is likely to forget The Next Generation. At the bar, Riker notices that there is a surplus of one particular model. “Why do you have so many Enterprise-Ds?” he asks. The bartender replies, “Oh, the fat ones? No one wants those.” It’s a joke that tries to position The Next Generation, arguably the most successful Star Trek series, as something underappreciated.

It is, to put it bluntly, a very strange choice. The Next Generation was a pop culture phenomenon. It was nominated for Outstanding Drama Series at the Emmy Awards. It cast a long shadow, and the Star Trek shows that followed were defined by their relationship to it. Deep Space Nine rebelled against it. Voyager got trapped emulating it. When it came time to end Enterprise, the final episode was a holodeck simulation that played during the Next Generation episode “The Pegasus.”

“The Next Generation” works hard to justify the nostalgia that drives it, to the point that the early conversation between Picard and Laris feels like it could have been an argument between Stewart and the producers about the need to return to The Next Generation. Pointedly, Picard himself is introduced in “The Next Generation” attempting to declutter, to get rid of the memorabilia that decorates Château Picard, while it’s Laris — a new character — who tries to preserve these elements.

“Jean-Luc, you don’t need to prove to me how ready you are for this, how in the present you are,” Laris tells Picard. “The past matters, and that’s okay.” Picard responds, “Laris, these things from my past. They are so dear to me. They are mementos of dear friends — old and new — but they’re memories.” He makes a valid point. Laris grimly counters, “A point comes in a man’s life when he looks to the past to define himself. Not just his future.” Picard protests, “I want a new adventure.”

There’s something inherently grim in the fact that Laris wins an argument that essentially writes her out of the show and that Picard then ends up with an adventure that is anything but “new.” It’s ultimately just familiar Star Trek iconography stitched together. The degree to which “The Next Generation” attempts to justify these choices suggests it knows how cynical and hollow all of this is. This is the first irony of the nostalgia that drives Star Trek: Picard season 3.

The second irony is that all of this invocation of the past feels weirdly fuzzy and inaccurate. It’s not an actual memory, but a conjured illusion. It’s a simulacrum of The Next Generation, but one blurred at the edges. For example, a key plot point involves Picard and Riker decoding a transmission by reference to the Borg virus that “scrambled (their) navigation” during “The Best of Both Worlds.” Except there was no Borg virus in “The Best of Both Worlds.” Nothing like that was in the episode, despite Riker’s insistence.

It is not quite right. More than that, it is not quite right in a way that is deeply unsettling given how eagerly the show embraces nostalgia. Crusher fires a phaser rifle from the Next Generation movies, but it has ammunition like a shotgun. This is not how those weapons have worked. Then on incapacitating her opponent, she closes in for a kill shot to vaporize the body. This is Beverly Crusher, perhaps the moral conscience of The Next Generation. It feels wrong — a feeling that builds given how insistent it is that this must be The Next Generation.

There is also the fact that none of this captures the actual storytelling of shows like The Next Generation or Deep Space Nine. Late in the episode, Raffi discovers a terrorist plot and arrives in time to witness the destruction of the Starfleet Recruitment Building. However, it doesn’t mean anything. It has no weight. Raffi’s plot hasn’t built properly to the moment, the location isn’t established, and the sequence isn’t treated as the culmination of anything. There’s no humanity to it. The consequences don’t feel tangible. It’s just something that happens.

That attack should be a game changer. It should establish stakes, like the bombing of the Starfleet Embassy on Vulcan at the start of “The Forge” in Enterprise, which killed Admiral Forrest (Vaughn Armstrong), or the bombing of the peace conference at the start of “Homefront” in Deep Space Nine, which hinges on something as simple as Avery Brooks’ delivery. But “The Next Generation” isn’t interested in this sort of storytelling, even if it’s what made those shows compelling, because it’s not a physical object from The Next Generation.

This is the problem with this sort of nostalgia-driven storytelling, which can often feel like a narrative cargo cult. It chases the recognizable artifacts and the iconography of beloved properties, without ever engaging with the storytelling mechanics that made them so compelling in the first place.