I have a bad track record with plants. Amongst my shameful history of minor negligence is the slow and unintentionally torturous manslaughter of a cactus. So it’s not clear why I find the core premise of Strange Horticulture so appealing: You inherit and run a plant shop in a 19th century fictionalized, dark fantasy England – the Lake District as described by Jeff VanderMeer, if you will.

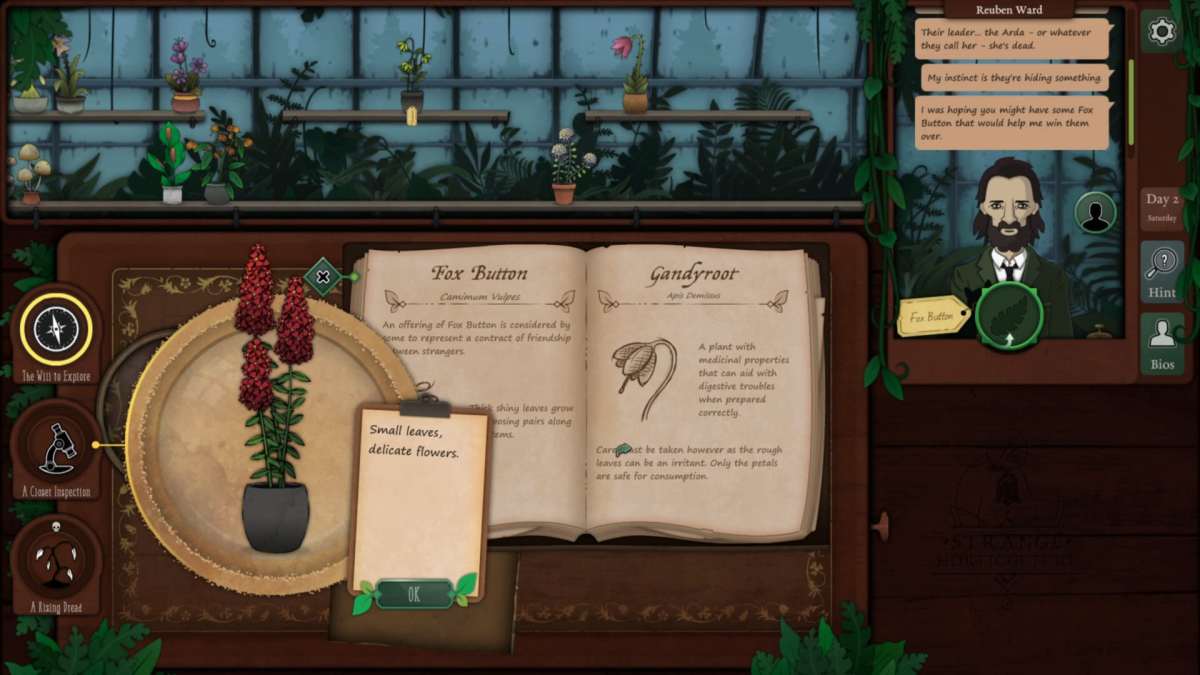

It’s also not clear if I’ll ever get used to the awkward UI and controls. Your greenhouse is squashed into a small, narrow bar at the top of the screen, looking increasingly busy and difficult to navigate as it gets filled with the game’s 70+ plants. On the right is the representation of the shop counter – you can ring the bell to bring in a new or returning customer. And your desk fills the rest of the screen, approximately two-thirds of it.

Everything is represented in 2D, and as the game progresses and items are acquired, it becomes more cramped and fiddly. When you want to click on your growing plant encyclopedia, you may very well accidentally open the large folded game world map or pick up the labels from the drawer instead.

Indeed, Strange Horticulture feels something like a genteel Papers, Please. In that title, the cramped conditions of your 2D border guard’s booth and work desk conspired with the game’s relentless time pressure and sparse pixel art to create a sense of stress, overwork, harsh uniformity, and ultimately oppression. It put you in an environment where you might make a mistake or be forced into a snap decision, which in turn opened up different plot points.

In contrast, Strange Horticulture’s lack of space merely comes from an academic obsession with collecting, cataloguing, and hoarding. Indeed, even though Strange Horticulture is rigidly divided into roughly two-and-a-half weeks, each day plays fast and loose with its sense of time.

Customers can be left waiting indefinitely as you take long excursions to the surrounding landmarks to find the plants they are after. The specimens in your greenhouse can be watered with about as much care as I afforded my poor cactus, but doing so will still yield more opportunities for countryside ambles to follow up a particularly difficult or obscure clue.

Even madness seems to wait on the game’s horticultural protagonist. If you make too many errors when identifying plans or mixing elixirs, your mind will quite literally shatter into pieces or become locked behind increasingly elaborate doors. However, you can take as much time as you like to put these pieces back together again or find the right key before being revived back to the start of a day.

These idiosyncrasies ultimately accommodate the game’s strengths. And the first of those strengths is the wonderful prose. It isn’t verbose or rich with branching dialogue options, but it isn’t overly minimal either. There is an eye for a deftly placed figure of speech as much as there is for carefully doled out world-building.

Strange Horticulture is light on explicit lore, but it manages a lot through suggestion, implication, and descriptions. They point to just the right elements of the action to keep the pace moving without losing sight of the smaller details that gradually build a sense of supernatural dread. Likewise, the characters don’t say an awful lot but feel richly drawn nonetheless – from the gossip-loving postman who brings you many of your clues, leads, and puzzles, to the snooty barrister who is at the mercy of your plant-dispensing knowledge.

That deep knowledge is Strange Horticulture’s second major draw and the main reason it feels so moreish. Following the game’s cryptic clues in search of new plants to add to your greenhouse, using them in response to customer requests or plot developments, cataloguing them in the game’s encyclopedia – it all has a Pokémon-like compulsion to it.

Granted, it requires suspension of disbelief that goes beyond the usual territory that comes with speculative fiction. It’s not clear, for example, why so many of the game’s possible antagonists are repeatedly willing to visit your shop, especially towards the conclusion of the story, when seemingly the entire world is looking for them. And perhaps it would have been better if the game tested your knowledge of previously collected plants more often, rather than being quite so eager to dispense new ones.

Nonetheless, Strange Horticulture is surprisingly satisfying as a horticulturist power fantasy. The game’s plants might be fictional, but there is a very real sense of achievement to remembering a previously identified specimen and its properties and to applying these correctly in response to an obscure request or an especially stubborn puzzle. In many ways, it is similar to 2007’s The Witcher.

CD Projekt Red’s first game may have been rough around the edges, but it indulged a singular commitment to role-playing as the witcher Geralt. It was possible to recognize plants on sight from their menu icons and to combine them based on in-game information or guesswork, rather than explicitly from potion recipes. And it was necessary to prepare for difficult fights by brewing and drinking the right potions beforehand.

Just as in the novels the game is based on, Geralt could be role-played as a keen and knowledgeable herbalist. It was a deep and at times frustratingly dense alchemy system that was greatly simplified by the time of The Witcher 3 – understandably so, given the broader commercial success the third installment was clearly aiming for, but it also lost a layer of role-playing satisfaction in the process.

In that sense, Strange Horticulture is more than just a well-written, addictively paced detective game with a unique premise. It’s a reminder that sometimes the effective application of knowledge and analysis can be just as satisfying as a well-animated sword swing.