I have an odd love of putting away the dishes in my kitchen. I don’t mind scrubbing down the shower and will pick up a vacuum every once in while, but there’s an extra sense of satisfaction I get while listening to the sound of softly clinking glass while sorting mugs and plates into my organized cabinets. I’m a similar geek for productivity when I’m bartending and knocking out drink orders, prepping for a family gathering in the kitchen, or crossing off small tasks and emails at work. So you can imagine my delight as indie games have been capitalizing more and more on the mechanic of productivity and task-based activities.

Task-based indie games have become a hit genre, asking players to organize, build business plans, and multitask. For every Celeste or Hades, there’s a title like Unpacking and Overcooked that focuses on project management or completing a job. Granted, one could extend this idea to argue that all games are task-based, in that games like Celeste have the added task of collecting strawberries to bake a pie. But that doesn’t quite count, as a task-based game in itself is about the merits of productivity.

Video games have always had objectives and sidequests, so what makes a task-based game unique? To get a full understanding of what the genre is, maybe it’s best to take a look at its evolutionary ancestor: SimCity.

In SimCity players manage their city’s day-to-day wellness, handling design, planning, and other tasks to keep the town afloat. But even if working over these tasks was engaging for an hour or more, talk to any gamer who’s played it and they will tell you they eventually became bored. SimCity itself probably understood it hadn’t gotten the formula quite right, as it installed the game’s most infamous mechanic: a disaster button to let players summon a tornado, alien attack, or, in later iterations, nuclear holocaust to wreak havoc on the city they were tasked with growing.

Gamers needed a reason to focus on the task at hand, and it would be the Tycoon series that offered a new model of how to make completing tasks actually fun. RollerCoaster Tycoon 2 may not be the first entry in the series, but it’s arguably the game that truly popularized objective task gaming as something that could be fun. Your job in RTC2? Build rides to increase a park’s value, manage a budget, and socially experiment with how much you could gouge park goers to maximize your park’s profits and growth.

There are indie games that came out this year that follow this same model nearly verbatim, with Bear and Breakfast, Two Point Campus, and even more Tycoon sequels with the questionably ethical recent version of Prison Tycoon. Other titles also found ways to take the model and turn it into a vehicle for some really terrific in-game storytelling.

The tear-jerking indie hit Spiritfarer has players managing properties and building living arrangements on their boat, but it uses these mechanics to offer a heartwarming and heartbreaking look at death and grief. Games like My Time at Portia, Garden Story, and of course the iconic Stardew Valley similarly emphasize managing daily tasks to grow your farm or community, but they offer similar insights into human connection and environmental themes.

Indie survival games like Don’t Starve, Subnautica, and Minecraft follow this same formula of completing this task, only instead of progression of an objective, it’s prevention of the character’s death. The player’s only chance at life is mining, farming, and resourcing the world around them through task-based mechanics. And while, sure, you might go hunting or fight a boss every now and then, the core gameplay is gathering and combining the materials you need.

Task-based indie games have also done more than just steal the concepts of their project management predecessors. A lot of the management titles mentioned above do owe their identity to bigger studio games that came before them, like a Tycoon game or Harvest Moon. But the indie gaming community has also given us new offshoots of what productivity can mean when it’s at the core of a game. Overcooked particularly comes to mind.

In Overcooked, one-to-four players are assigned with running a kitchen and preparing dishes for an ever-growing list of customers. The kitchens themselves are chaotic, sometimes in a haunted house with floating tables, others miles above the earth in an actively on-fire hot air balloon. But despite the circumstances under which your team is cooking, your goal is simply to get that burger with lettuce and ketchup to the service counter.

Despite the heart-pounding anxiety of a ticking clock and having to remember to wash dishes, Overcooked will also create an intense zen in players as they focus on each task that needs to happen to get the job done with a team. And this teamwork often requires not just immaculate communication, but to get three stars on the hardest levels, you and your team will need impressive unspoken understanding as well.

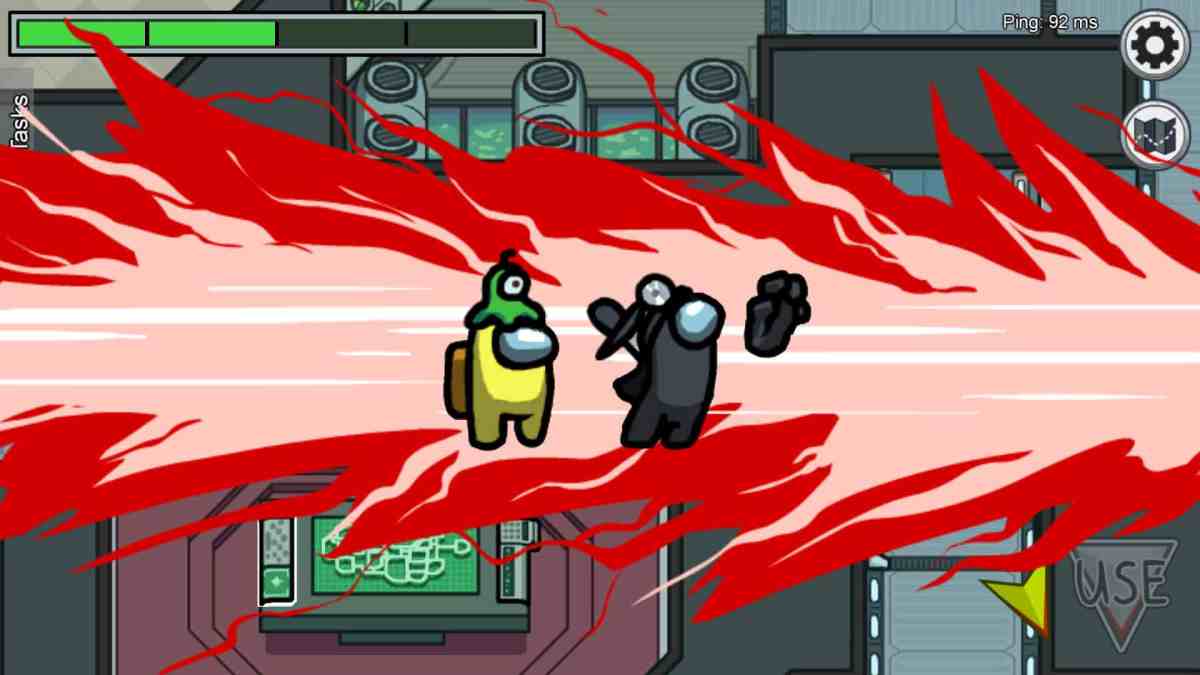

Overcooked of course is only the most popular example of indie games’ ability to innovate what tasks can accomplish in their game. Last year’s Unpacking offered a sweet coming-of-age tale all through the mechanic of placing household items in new spaces. Papers, Please weaves an eerie narrative of political uncertainty while the player is simply handling the bureaucratic tasks of checking paperwork at a checkpoint in Eastern Europe. Even the gigantic success of something like Among Us puts completing simple tasks around the ship at the forefront of gameplay, its horror elements only elevated by the literal need to fix a navigation system or take out the trash in order to survive.

And while the context for all these games is radically different, the simple mechanics make them not only addictively productive to engage with, but easier for the average person to engage with in the first place. They all use task-based mechanics to connect with that little part of our brain that releases endorphins when we can check one more thing off our to-do list. But while they’re gratifying to our simple lizard brains that scream to “do the thing,” they still stimulate our emotions and empathy as well.

When I put my dishes away, in reality, I’m not just putting my dishes away. I’m also thinking about a million other small things I haven’t had time to process while working. As I place the pots and pans back into the cabinet, I’m sorting my own emotional baggage in my head. It’s in this zen focus that I can see the big picture of thoughts I need to table, put away, or circle back to later. No wonder the most successful indie games offer a similar chance for your brain to process their art and meaning, while you tackle the simple task of just digging up some turnips or placing a virtual college degree on a virtual wall.