Terminator Genisys is one of the worst blockbusters of the past decade. It is also one of the most revealing.

Genisys is the third (of four) attempts to produce a sequel to Terminator 2: Judgment Day, an exercise that seems doomed by the requirement that any follow-up would have to reverse or undo that hard-earned happy ending. Genisys follows on from Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines and Terminator Salvation, the fifth in a six-film franchise that has yet to produce Terminator 4.

Genisys was a notoriously troubled production. Veteran Game of Thrones director Alan Taylor arrived on Genisys from the ill-fated Thor: The Dark World, reunited with actor Emilia Clarke. According to Clarke, Taylor was “eaten and chewed up on Terminator. He was not the director I remembered. He didn’t have a good time. No one had a good time.”

The set of Genisys was reportedly so unpleasant that the crew on the neighboring set of the famously troubled Fantastic Four reboot had jackets made that read, “AT LEAST WE’RE NOT ON TERMINATOR.” That chaos is evident on screen.

Genisys is a spectacular misfire, burdened with mountains of exposition and characters who appear and disappear almost at random. It has no internal coherence, no lofty ambitions, no artistic allusions. Rather, it exists as the purest distillation of a certain approach to the management of established intellectual property. Genisys accidentally reveals a lot about the decisions that drive these movies and the forces at play in them.

Genisys is very much an example of brand management. It is a studio taking a product with brand recognition and trying to break it down into its constituent elements so that those elements might be repackaged and reworked into a vaguely new shape that can be sold back to a presumably eager fan base. It is an assembly line picture for the franchise age, the scars tracing a map on celluloid.

Like so much of modern pop culture, Genisys is rooted in nostalgia. It doesn’t matter that there hasn’t been a consensus-good Terminator movie since Judgment Day. It only matters that the name carries some weight that might make it easier to market. Accordingly, Genisys appeals to nostalgia for the first two films.

On a set visit, Taylor assured reporters that the “first two films are our compass, inspiration and our guide.” Those assembled journalists were told that Genisys would “preserve” the events of the first two films while “entirely wiping away” everything else, acknowledging that the later films and the spin-off had not accrued enough pop culture cachet to justify retention.

Genisys treats the original Terminator and Judgment Day as a source of religious awe. The film slavishly reproduces several sequences from Terminator, such as the arrival of the T-800 (Arnold Schwarzenegger) at Griffith Park and Kyle Reese’s (Jai Courtney) procuring of a set of Nike runners themselves slavishly recreated for the film.

Early in the film, the T-800 climbs into the time machine to make his journey back to Los Angeles in May 1984. He kneels, reflecting how he was introduced in Terminator. Taylor shoots the sequence to convey a sense of wonder, as if this is an act of devotion. Later, when Reese uses the device, he levitates amid a swirl of lights as the music swells. It is almost a rapture.

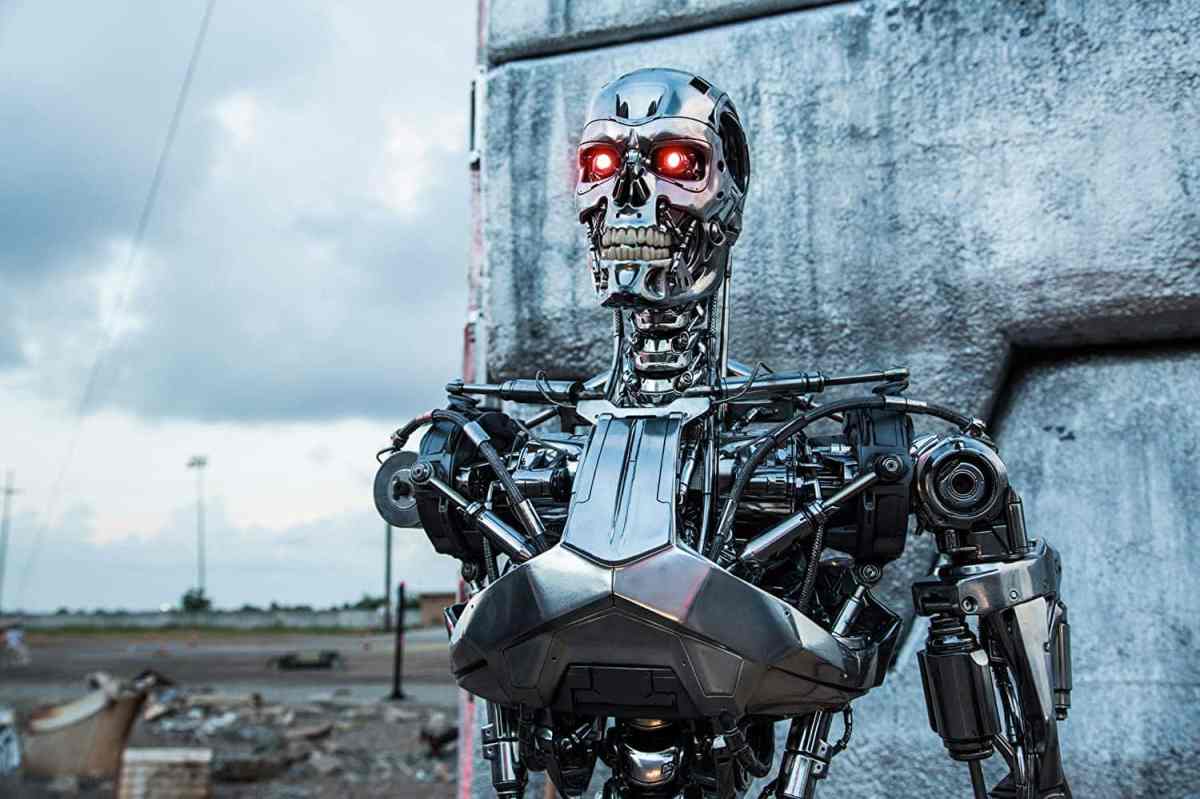

The opening moments of Genisys are committed to slavish recreation, using a blockbuster budget and modern technology to realize the futuristic conflict only hinted at in Terminator and Judgment Day while offering a computer-generated simulation of Schwarzenegger as he appeared in 1984.

However, something interesting happens when Kyle Reese is sent back in time. The first is that the past becomes undone. The narrative coherence of Terminator and Judgment Day unravels as the film becomes an excuse to simply wallow in the iconography of the past completely divorced from any meaningful context.

Genisys offers a series of disconnected references to those two films. Like in Judgment Day, there is a shape-changing liquid metal T-1000 Terminator that disguises itself as a Los Angeles police officer. However, he is played by Lee Byung-hun rather than Robert Patrick and appears in 1984 rather than 1991. This is how Genisys operates, conflating the two first films.

When Reese encounters Sarah Connor (Clarke) in 1984, he doesn’t meet the waitress from Terminator, but the hardened anti-social survivor from Judgment Day. He also discovers that she has her own companion T-800 model named “Pops” (Schwarzenegger), recalling the surrogate father figure that the cyborg became in Judgment Day rather than the killer machine in The Terminator.

The result of these choices is effectively to remove these elements from anything resembling a specific time or place and to instead render them as archetypes, a jumble of simulacra that look familiar enough to stoke nostalgia.

This is how multimedia companies approach intellectual property. Disney, for example, has a history of repurposing characters and imagery outside their original context. There are reasons to want to divorce the iconography of the first two beloved Terminator films from the films themselves too.

The Terminator and Judgment Day are the work of director James Cameron. Cameron is a storyteller with a strong voice and sensibility. It is easier to draw a line from Aliens to Judgment Day to Avatar than it is to connect Judgment Day to any of its four sequels. Genisys plays like an attempt to boil down elements of Cameron’s films so they might be reconstituted into another shape.

This is quite similar to Hollywood’s efforts to remake both Total Recall and RoboCop in the years leading up to the release of Genisys. These remakes treated both cult sci-fi films as intellectual property to be harvested, stripping out director Paul Verhoeven’s unique sensibility. The goal was to take a property that was beloved because of its distinctive aesthetic and recycle it as a modern blockbuster that was both recognizable and generic.

Taylor had done something similar on Thor: The Dark World, where he had replaced original director Patty Jenkins. Jenkins had parted ways with Marvel, feeling unable to realize her vision of the Thor sequel. Taylor offered something safer.

Taylor is not a director who is defined by a distinctive vision. When he was in talks to direct Genisys, he cited Christopher Nolan’s Batman films as an inspiration. He borrows imagery out of context. John’s (Jason Clarke) introduction, dangling from the ceiling to save a young Reese (Bryant Prince), mirrors the introduction of Thomas Wayne (Linus Roache) in Batman Begins. A helicopter chase evokes The Dark Knight. It’s just imagery reiterated and regurgitated.

With characters reduced to static archetypal action figures, Genisys substitutes continuity for characterization. By the time the film introduces Sarah Connor and Pops, both are recognizable as iterations of the characters they were at the end of Judgment Day. Their journeys are complete. There is no meaningful way to develop them beyond that.

Instead, what little drama exists is derived from the faded memory of earlier films. Sarah is wary of the fact that she will fall in love with Reese and that he will die, as happened in The Terminator. She summarizes, “You die. That’s what happens. We fall in love, you father John. And then – in less than 48 hours – you die protecting me.” That’s not character drama; that’s a Wikipedia plot summary.

Yet, for all that the past remains a trap in Genisys, it is still better than the future. In The Terminator and Judgment Day, John Connor always represented hope for a future beyond the apocalyptic hellscape created by Skynet. John Connor would unite humanity. This was the kernel of hope in the series’s dark future, the belief that something better lay beyond.

Genisys is unable to conceive of that hopeful future. The moment that Reese is sent back in time, Clarke is attacked by a personification of Skynet (Matthew Smith). “You didn’t think it would be that easy, did you?” the villain taunts. In a twist revealed ahead of time by the trailers, perhaps to head off potential fan criticism, John Connor is turned into a new breed of Terminator.

It is a breathtakingly cynical move, a firm rejection of any closure for the Terminator franchise. After all, John Connor’s victory over the machines had always been presented as the ultimate ending of the Terminator franchise, the point at which the story was finally over. However, reflecting the idea that modern franchises must continue in perpetuity, that ending must be destroyed.

Genisys is the only Terminator movie to offer Skynet any characterization. It chooses to treat Skynet as a metaphor for evolution or growth. “Primates evolve over millions of years,” Skynet taunts. “I evolve in seconds.” If development and change are weapons of Skynet, of course John Connor becomes its avatar. “John is not humanity’s last hope anymore,” Sarah warns Reese. “He’s Skynet’s.”

Genisys ends with an embrace of the status quo. Despite Sarah’s insistence that she can choose and Reese’s observation that the future is not certain, Genisys closes with the familiar Terminator tropes: Schwarzenegger as a friendly cyborg, Sarah and Reese as a couple, a closing voice over asserting the importance of free will. Reese even creates a stable time loop with his younger self.

Genisys is a terrible film, but one that openly and nakedly speaks to so much of how Hollywood approaches modern film franchises. It fetishizes the past without understanding it, inherently suspicious and wary of anything new or different from what came before. It boils down beloved older films into images divorced from meaning or context, numbingly reiterated over and over.

Perhaps the true dark future predicted by the Terminator franchise is not a boot stamping on a human face or even a robot foot crushing a human skull. Perhaps it is simply a snake eating its own tail – forever.