The most interesting thing about The Rings of Power is how simple it is.

This is not a surprise. It is an adaptation of the works of J.R.R. Tolkien. Tolkien adopted a straightforward moral outlook, with clearly defined boundaries between good and evil. There was little moral ambiguity in The Lord of the Rings, and this carries over to The Rings of Power. This is a world where the heroes wear flowing white robes and have long blonde hair, while the villains are monsters clad in black armor or caked in mud. There is good and there is evil, with little in-between.

The Rings of Power is positioned as the television event of the year. It is easily the most expensive television show ever produced. It is the rare Amazon streaming show where the company actually has something meaningful at stake. It is reportedly the result of former Amazon CEO (and occasional richest man alive) Jeff Bezos demanding a monoculture-shaping hit like Game of Thrones. Bezos has strong ideas about what a show needs to be successful and heavily noted The Rings of Power.

Of course, streaming metrics are inherently proprietary and opaque. It’s hard to know how a show like The Rings of Power is actually performing, let alone how it needs to perform. Nevertheless, reviews for the show have been strong, and Amazon has claimed that 25M people watched the premiere in its first 24 hours. (The company declined to specify what precisely constitutes a “watch” for that metric.) While it is early days, it seems safe to concede The Rings of Power is not a failure.

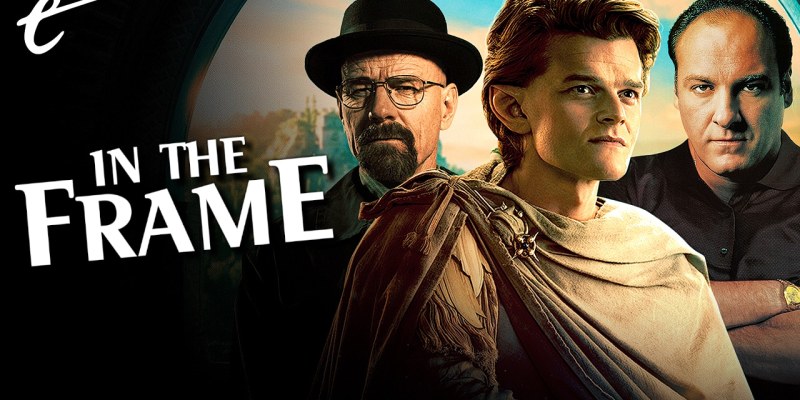

More to the point, The Rings of Power seems to signal a broader shift in popular culture in general and in high-profile television in particular. It feels diametrically opposed to what has been the default model of prestige television since the turn of the millennium. The show’s clear moral boundaries, and its stark delineation between good and evil, offer a very different approach to storytelling within the medium than the so-called “Golden Age of Television.”

The Golden Age of Television began around the turn of the millennium, neatly overlapping with the theatrical release of Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy. This era of television production was defined by a moral ambiguity and uncertainty, with shows built around characters that could charitably be described as “anti-heroes.” These series tested the limits of the audience’s capacity for empathy and often avoided easy answers in favor of a murkier moral worldview.

The Sopranos was built around Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini), who choked a man to death in the show’s fifth episode. In Breaking Bad, Walter White (Bryan Cranston) lasted three episodes before choking his first victim with a bike lock. The Shield made it to the end of the first episode before Victor Mackey (Michael Chiklis) murdered Terry Crowley (Reed Diamond). On Mad Men, Don Draper (Jon Hamm) was only indirectly responsible for deaths and only dreamed of killing ex-girlfriends.

There is a reason that Brett Martin’s history of this era of television was known as Difficult Men, although the term arguably applied just as much to television auteurs like David Chase or Matthew Weiner as to any of their subjects. However, this ambiguity extended beyond the protagonists of many of these era-defining shows. Many of the shows themselves were built around a sense of moral relativity, inviting the audience to question traditional delineations between right and wrong.

The Wire explored the Baltimore drug trade with an endearing humanism, allowing its criminals to be just as compelling and sympathetic as the police officers pursuing them. The Americans asked the audience to root for two Soviet spies (Keri Russell and Matthew Rhys) as they infiltrated Reagan’s America. Battlestar Galactica offered a pointed commentary on the War on Terror by often casting its protagonists as terrorist insurgents under enemy occupation.

The most obvious point of comparison for The Rings of Power is perhaps Game of Thrones, a fantasy epic that explicitly rejected the clear-cut worldview of something like The Lord of the Rings. Westeros was a world built around cynicism and ambiguity. At its core, Game of Thrones was a story about how there was no such thing as a good king or queen, however much the audience might want that to be the case.

This era of television drew heavily from the moral ambiguity of the 1970s “New Hollywood” movement in cinema. The characters on The Sopranos would frequently wax lyrical about The Godfather, even watching The Godfather Part II before their own trip to Italy. The opening episode of Better Call Saul quotes directly from Paddy Chayefsky’s Network and Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz. Even the concept of The Americans feels like a Cold War riff on something like The Eagle Has Landed, in which the audience follows a crack Nazi commando team trying to kidnap Winston Churchill.

This ambiguity extended beyond television. It was also evident in some of the bigger blockbusters of the era. Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy was built around the ambiguity over whether the power fantasy of Batman (Christian Bale) was inherently a good thing. Shane Black’s Iron Man 3 challenged its audience by arguing that simplistic comic book enemies like “the Mandarin” (Ben Kingsley) were just convenient distractions from more insidious issues closer to home.

Of course, the Golden Age of Television is over, even if critics might disagree about when exactly it ended. There were a lot of pieces from writers like Oliver Lyttelton and Andy Greenwald that argued for the overlapping endings of Breaking Bad and Mad Men as the logical endpoint of the era. In hindsight, Sonia Saraiya remarked that Mad Men was “the last show in the medium’s sudden transformation” that had begun with The Sopranos.

Assuming that the Golden Age of Television really is over, the question remains: what next? Indeed, for years following the end of Breaking Bad and Mad Men, it seemed like the echoes and shadows of that Golden Age lingered on, with an abundance of almost-but-not-quite-as-good gritty dramas like Ozark or Ray Donovan, shows that occasionally felt like an after-after-party as a new dawn approached. Even great shows like The Deuce or The Plot Against America failed to gain traction.

The more interesting shows in this interregnum actively engaged with the legacy of these morally ambiguous antiheroes. Terence Winter followed up his work on The Sopranos by crafting Boardwalk Empire, a show in which the central antihero was less seductive than Tony Soprano. The show Succession finds a way to make its protagonists’ absurd wealth and privilege look more unsettling than alluring. There is a sense that these moral boundaries are being redrawn.

Better Call Saul was a show that often seemed in direct conversation with Breaking Bad, to the point that Jimmy McGill (Bob Odenkirk) often felt like a eulogy for these sorts of antihero drama. This was particularly obvious in the show’s final stretch, in which the series adopted the stark black-and-white cinematography of classic “Crime Doesn’t Pay” Production Code-era Hollywood. The ending of Better Call Saul offers a much less ambiguous ending for Jimmy than Breaking Bad did for Walter.

The most popular show on cable is Yellowstone, which obviously shares a lot of the DNA with those earlier antihero dramas. It hybridizes the form with 1980s soap operas like Dynasty and Dallas, both of which had recent television revivals. Yellowstone accepts that John Dutton (Kevin Costner) is not a nice man and that those opposed to him usually have a legitimate grievance, but the show is never really interested in interrogating or challenging Dutton. He’s the least bad option.

Even House of the Dragon feels decidedly less ambiguous than Game of Thrones. Game of Thrones was ambivalent about the eponymous game, with Arya Stark (Maisie Williams) touring traveling among the so-called “small folk” who existed outside of the world of the ruling class. In contrast, House of Dragon feels more insulated within its world of royalty and a lot less cynical about Rhaenyra (Milly Alcock, Emma D’Arcy) than Game of Thrones was of Daenerys (Emilia Clarke).

The Rings of Power is much clearer in its delineation between good and evil than Succession, Better Call Saul, Yellowstone, or House of the Dragon. It opens with Galadriel’s (Morfydd Clark) assertion that “nothing is evil in the beginning.” A young Galadriel (Amelie Child-Villiers) discusses the nature of light and darkness with her brother Finrod (Will Fletcher). When she protests that her brother’s logic “seems so simple,” he replies, “The most important truths often are.”

The moral clarity of The Rings of Power resonates with broader pop culture. In recent years, the Marvel Cinematic Universe has largely embraced a simplistic and unambiguous sort of heroism, even when it probably shouldn’t have. Top Gun: Maverick is the biggest movie of the year, offering a dose of old-fashioned patriotic derring-do so clear-cut that the movie never bothers to place its aerial action in any geopolitical context, instead lifting its cues from Star Wars.

In some ways, this reflects the shift in American popular culture that took place at the end of the 1970s and into the 1980s, as the moral ambiguity of New Hollywood movies like The Godfather, Taxi Driver, and A Clockwork Orange gave way to less complicated blockbusters like Superman, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Return of the Jedi, and the original Top Gun. History doesn’t necessarily repeat, but it does rhyme.

It’s easy to understand why audiences might be drawn to more simplistic and less complicated narratives, with clearer delineations between good and evil. Much like the end of the 1970s, America is emerging from a period of political corruption and turbulence, so these wholesome stories resonate with an audience that wants to believe that “the most important truths” can be “so simple.”