This discussion contains slight spoilers for The Creator.

Apocalypse Now is obviously a huge influence on Gareth Edwards, the director and co-writer of The Creator.

Edwards included Apocalypse Now on his ballot for the 2012 Sight & Sound poll, alongside Baraka. In interviews, Edwards has talked about how – “stylistically,” at least – Apocalypse Now is “one of the greatest films ever made.” He has been very candid about how Apocalypse Now informs his own filmmaking, conceding, “I’m always trying to get a bit of Apocalypse Now into anything I do.” Indeed, that influence is very obvious just looking at the films themselves.

Edwards’ first feature, Monsters, opens with night vision footage of American soldiers psyching themselves up by chanting “Ride of the Valkyries,” an allusion to one of the most famous and iconic scenes from Apocalypse Now. While Monsters is a science fiction film set largely in Mexico, it owes a lot to Apocalypse Now, most obviously with its depictions of decaying American ordinance and a trip up river by boat. Roger Ebert even likened Monsters to Apocalypse Now in his review.

While Edwards would follow Monsters with two big franchise films, Godzilla and Rogue One, that influence would return on The Creator, his most recent project and his first since Monsters not to be based on existing intellectual property. The bulk of the film was shot on location in Thailand, and takes place in the fictional futuristic “Republic of New Asia”, a geopolitical entity that is harboring rogue artificial intelligence from the American government.

The idea for The Creator came to Edwards while visiting the production of Jordan Vogt-Roberts’ Kong: Skull Island in Vietnam. He looked at the landscapes, imagining science fiction layered over it. “So I just go over, just for a day, and I end up staying a week and traveling all up and down Vietnam with him and seeing imagery that I associate with, obviously, the Vietnam War and stuff, but through a sort of science fiction lens, because I had this movie in my head,” ” he explained. “And I’d picture that imagery, and after a while, it was like watching Apocalypse Now, but set in the Blade Runner universe.”

The Creator is saturated with imagery pulled directly from the Vietnam War. The movie is set between 2065 and 2070. Those dates mark the centenary of the arrival of the first American combat troops in Vietnam and the spread of the war to Cambodia. Much of the plot focuses on N.O.M.A.D., an orbital platform allowing the American military to bomb artificial intelligence strongholds in other nations, recalling America’s bombing of Cambodia as part of the Vietnam War.

The film also draws heavily from Vietnam War movies. After all, this is how Edwards would have experienced the conflict. Not only was he born in 1975, two years after the Paris Peace Accords, he is also British. As such, the cinematic language of The Creator evokes movies like Apocalypse Now and Platoon. A raid on a peaceful village recalls that “Ride of the Valkyries” sequence, and Allison Janney’s Colonel Howell suggests Tom Berenger’s Staff Sergeant Barnes, down to the facial scars.

Much has been made of the perceived timeliness of The Creator, a movie about the threat of artificial intelligence that is releasing in the midst of a very public debate about the development of that technology. Edwards acknowledges that the film is timelier than he could have anticipated. “When I started writing this in 2018,” he stated, “AI was up there with flying on the moon. Something you would see in your lifetime? Probably not.”

As such, The Creator isn’t really about artificial intelligence. It is using artificial intelligence as a metaphor. “It was used as a device, as people who are different to us, like ‘the other,’ and exploring that idea a little bit,” Edwards remarked of his vision of the film. “In terms of where AI is going, the problem … you [read this interview] in a year or even six months, you’re going to look an idiot for trying to predict AI.”

As such, The Creator is not just an allegory for the Vietnam War, it explores how the West talks about the Vietnam War. In particular, how the American gaze tends to dehumanize the Vietnamese. “The idea was that the Vietnamese, they weren’t really people,” explains historian Nick Turse, recounting how soldiers were encouraged to use racial slurs. “Anything to take away their humanity, to dehumanize them and make it easy to see any Vietnamese — all Vietnamese — as the enemy.”

This has been a strong criticism of Vietnam War movies. Even those movies that criticized the conflict or the actions of American soldiers still tended to at best ignore and at worst caricature the Vietnamese experience. “It was an antiwar movie about the war in Vietnam, but the movie was about Americans,” noted author Viet Thanh Nguyen of Apocalypse Now. “The Vietnamese were silent and erased.” It is still a point of contention over movies like Da 5 Bloods.

To his credit, Edwards has consistently engaged with this subtext of the movies that he loves. Even in Monsters, there is a sense that the film is critiquing its two American tourists, Andrew (Scoot McNairy) and Samantha (Whitney Able), who wander through a disaster zone. Andrew snaps photos of dead children that he can sell to the American press. Samantha is a socialite looking to escape her upcoming engagement. They are both privileged tourists in the aftermath of a catastrophe.

Indeed, some aspects of Monsters feel even more pointed today, such as the discovery that the United States has built a giant wall on its southern border to keep the “monsters” out. “Yeah, it’s like we’re imprisoning ourselves,” Samantha muses at one point. Staring out at the wall from the top of some ruins, Andrew observes, “You know, it’s different looking at America from the outside.” It is a little clumsy and naïve, but Monsters is a film about Western narcissism.

That carries over to The Creator. Throughout the film, there’s an emphasis on how human beings refuse to think of their enemies as living creatures. “They’re not people!” Joshua (John David Washington) insists. “They’re not real!” When he shoots one through the chest, he insists that he didn’t kill it. “It’s off,” he explains. “It turned it off. Like the TV.” Even as the robots scream and beg, Joshua refuses to see them as anything other than monsters. “They don’t feel shit,” he explains of their agony. “It’s just programming.”

The Creator makes the point that the artificial intelligences pose no threat to humanity. The nuclear bomb that destroyed Los Angeles, sparking the war, was “a coding error” by humans, recalling the Gulf of Tonkin Incident. “Do you know what will happen to the West if the AI win this war?” asks Harun (Ken Watanabe). He answers his own rhetorical question, “Nothing. We just want to live in peace.” The war is one of Western expansion, the artificial intelligences a convenient target. There is no “domino theory.”

Indeed, one of the central recurring themes of The Creator is the question of what happens if these human characters start to see these entities as people. Joshua is introduced working undercover, having seduced machine sympathizer Maya (Gemma Chan), itself a version of the familiar story of the American soldier who falls in love with a Vietnamese woman. “Do not go native on me,” advises Joshua’s supervisor, Drew (Sturgill Simpson), rendering the imperialist subtext as text.

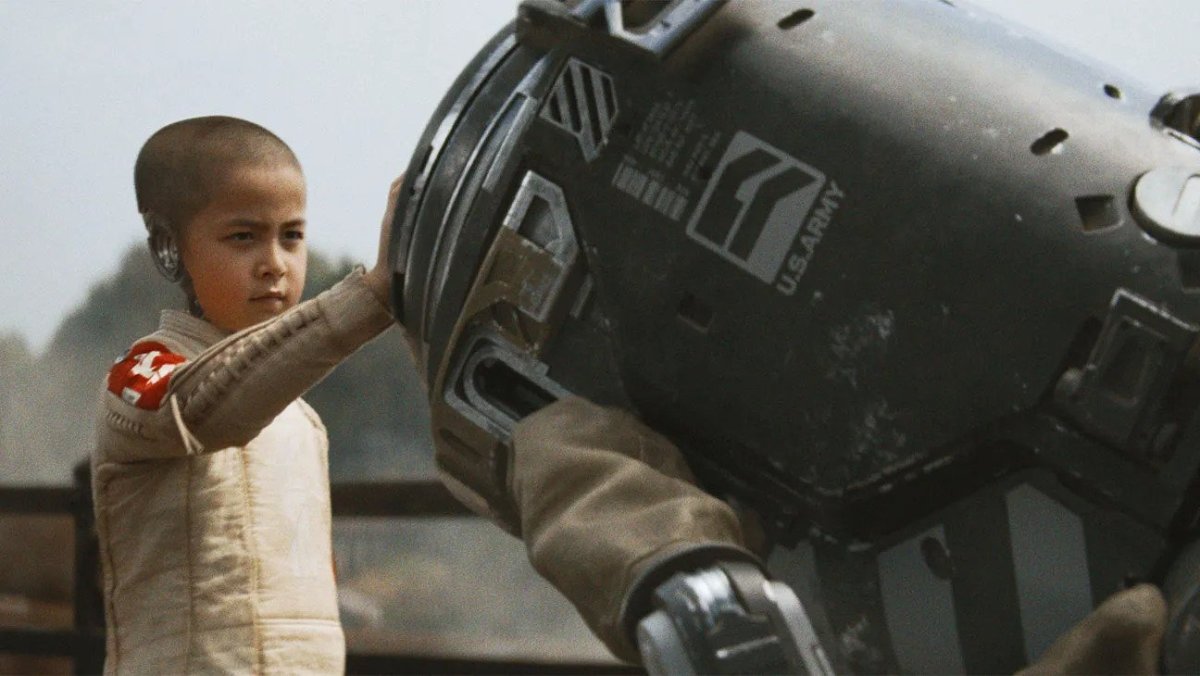

Throughout the movie, there’s an emphasis on human beings “donating [their] likeness,” effectively allowing robots to wear copies of their faces. This makes it harder to see them as objects. When Joshua is assigned to track down an advanced artificial intelligence that he comes to call “Alfie” (Madeleine Yuna Voyles), General Andrews (Ralph Ineson) pointedly insists on calling it “the Weapon.” Joshua cannot see Alfie that way. “It’s a kid,” he insists. He sees Alfie as a person.

Throughout the movie, there’s an emphasis on human beings “donating [their] likeness,” effectively allowing robots to wear copies of their faces. This makes it harder to see them as objects. When Joshua is assigned to track down an advanced artificial intelligence that he comes to call “Alfie” (Madeleine Yuna Voyles), General Andrews (Ralph Ineson) pointedly insists on calling it “the Weapon.” Joshua cannot see Alfie that way. “It’s a kid,” he insists. He sees Alfie as a person.

Of course, this is a classic science fiction trope, one that informs movies as diverse as District 9 or Starship Troopers. It informs episodes of television like “Men Against Fire” from Black Mirror or “The Devil in the Dark” from Star Trek. This theme of othering and oppression has been a key metaphor in stories about robots going back to R.U.R.. However, The Creator stands out for taking this metaphor and applying it directly to not only the Vietnam War, but also cinematic depictions of that conflict.

To be fair, as with Monsters, there is a certain clumsiness to The Creator. As much as these are films about how myopic Western perspectives can be in how they view the outside world, there is a sense that both films are still trapped within that worldview. Monsters is aware of how self-centered Samantha is and how predatory Andrew is, but it is still ultimately their story. The pair come together through their shared experience. Their journey is still something that enriches them.

As much as The Creator feels like a commentary on the way that decades of Vietnam War movies have dehumanized the Vietnamese, it also marginalizes the perspective of its South East Asian characters. The film doesn’t give any focus to the politics or the inhabitants of “the Republic of New Asia.” Outside of a few brief snippets of interactions that suggest a bond forged in humanism, there is no exploration of what this alliance means in cultural or political terms.

Although the robots appear to practice a sort of Buddhism, there is no exploration of or connection to the culture from which Buddhism emerged. It feels like an aesthetic that the film applies to these creatures, without any real consideration of how it might meaningfully apply to them. The Creator is an ambitious film about the dehumanizing effect of the Western gaze, specifically as applied to South East Asia. However, even while critiquing it, the film cannot break free of it.