This is a charged moment. There are legitimate questions being asked about the state of democratic and social structures. Critics have tried to render those questions through pop culture, as if hoping to garner some understanding of the collective unconscious by parsing the stories that we tell one another. Naturally, given their prominence as a cultural force, there has been a lot of discussion of contemporary film and television’s obsession with superheroes and what that means today.

As one of the most popular superheroes on the planet, Batman is inevitably drawn into these discussions. At a time of increasing income inequality and where the historically unpopular president of the United States has built his brand identity as a billionaire, what does it mean to tell stories about a wealthy man who uses his fortune to act as an unchecked vigilante? It has become cliché to argue Bruce Wayne should pay more tax or donate his fortune if he really wants to help Gotham.

There are two obvious responses to these criticisms. The first is to accept that Batman stories operate with a basic suspension of disbelief. The audience must accept the starting premise of a billionaire crime-fighter who dresses up as a bat to punch clowns in the face. After all, if Bruce donated all his money to charity instead of being Batman, it would not make for a particularly satisfying Batman story.

The second response is to fold these criticisms into the character’s stories. Over the years, the comics have engaged with the idea of Bruce’s relationship to Gotham as a billionaire. In the late ‘60s, the Wayne Foundation was introduced as a charitable foundation that helped Bruce use his tremendous resources to fight poverty in the city. Characters like Leslie Thompkins and Jason Todd offered a glimpse of Gotham’s disadvantaged.

No Batman story has gone as far as Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight Rises in deconstructing the character’s wealth and privilege. It has been argued that billionaires should be “abolished,” and The Dark Knight Rises almost agrees. By the end of the film, Bruce Wayne has been declared bankrupt and then dead, his property has been redistributed to “the city’s at-risk and orphaned children,” and a new working-class Batman has been established. This is radical.

Nolan tends to be a relatively private person, and so his own politics are a frequent subject of debate. However, he has expressed concern about income inequality and cult of personality. “Whether you’re talking about Silicon Valley billionaires or politicians, I think we’re living in an era that over-prizes individuality at the expense of community,” he argued in 2018. “The idea that benevolent capitalists will just take care of us and the people on top will magically distribute wealth and happiness and security to us little people … no. It’s time we wised up.”

The Dark Knight Rises was one of the first major Hollywood blockbusters to engage with the 2007-2009 Great Recession. Income inequality arguably wouldn’t be foregrounded in high-profile mainstream cinema until last year with the release of movies like Knives Out, Parasite, Hustlers, and Joker. Contemporary blockbusters were either still working through the War on Terror like Iron Man 3 or Star Trek Into Darkness or broaching broad environmental themes like Noah.

Of course, The Dark Knight Rises has been read as a reactionary parable, its story of revolution interpreted as a right-wing fable about the dangers of the Occupy Wall Street movement. (“Occupy Gotham“ was a common refrain from those making the connection.) The timeline does not support such a reading. Occupy Wall Street only began on Sept. 17, 2011, while The Dark Knight Rises wrapped production on Nov. 14, 2011. Despite fevered speculation, it did not film the protests.

Still, this critique of The Dark Knight Rises argues that the film is the story of a failed revolution by the lower classes, suppressed by a billionaire with the assistance of Gotham’s police force. This reading of the film is particularly charged in the context of a broader discussion about the role of police officers in popular culture and the glorification of police violence. In truth, The Dark Knight Rises is a much more complex piece of work than this summary suggests.

Bane (Tom Hardy) is not a socialist revolutionary. While he promises to give power back to “the people,” he entrusts Talia (Marion Cotillard) with the trigger of a nuclear bomb as leverage. He enforces his rule with an army of mercenaries in military fatigues, also freeing and arming organized criminals. The military and police prevent an exodus. He patrols Gotham with tanks in desert camouflage, recalling the occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan. John Blake (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) likens him to “a warlord” of “some failed state.”

Bane is ultimately revealed as a fraud — his escape from the Pit is nothing but a lie. Even members of the Occupy New York movement recognized this was not a portrayal of their protests — it was “about revenge more than revolution.” It might even be classed as resentment. Bane has been co-opted not as an icon of the radical left, but as a meme associated with the alt-right. Bane’s rhetoric has not been echoed in the appeals of figures like Bernie Sanders, but instead by President Donald Trump.

When released in 2012, The Dark Knight Rises stood in contrast to the Obama-era optimism of films like Joss Whedon’s The Avengers. Indeed, the film’s first act makes a point of having its characters enjoy decadent celebration. Jim Gordon (Gary Oldman) is dismissed as “a war hero,” redundant in “peace time.” Mayor Garcia (Nestor Carbonell) gives a speech about how Gotham is a “city without organized crime.” This is a false dawn. The Dark Knight Rises cannot embrace this optimism.

Outside the grounds of Wayne Manor, the people of Gotham are suffering. Bodies are washing up in storm drains as the city struggles to provide shelter for the children aging out of its modest social services. Nobody cares apart from John Blake. A working-class orphan who grew up in a boys home rather than a fancy manor, Blake serves as half of the social conscience of The Dark Knight Rises, balanced by the cat burglar Selina Kyle (Anne Hathaway).

Selina is the film’s moral compass. Infiltrating a fundraiser, the camera shares her disdain for the rich idiots in tuxedos fighting over lobster. She sighs, “You’re all gonna wonder how you ever thought you could live so large and leave so little for the rest of us.” Billionaires are dangerous. John Daggett (Ben Mendelsohn) brings Bane to Gotham and provides the “money and infrastructure” that empowers Bane’s coup, believing he can “control this necessary evil” for his own ends.

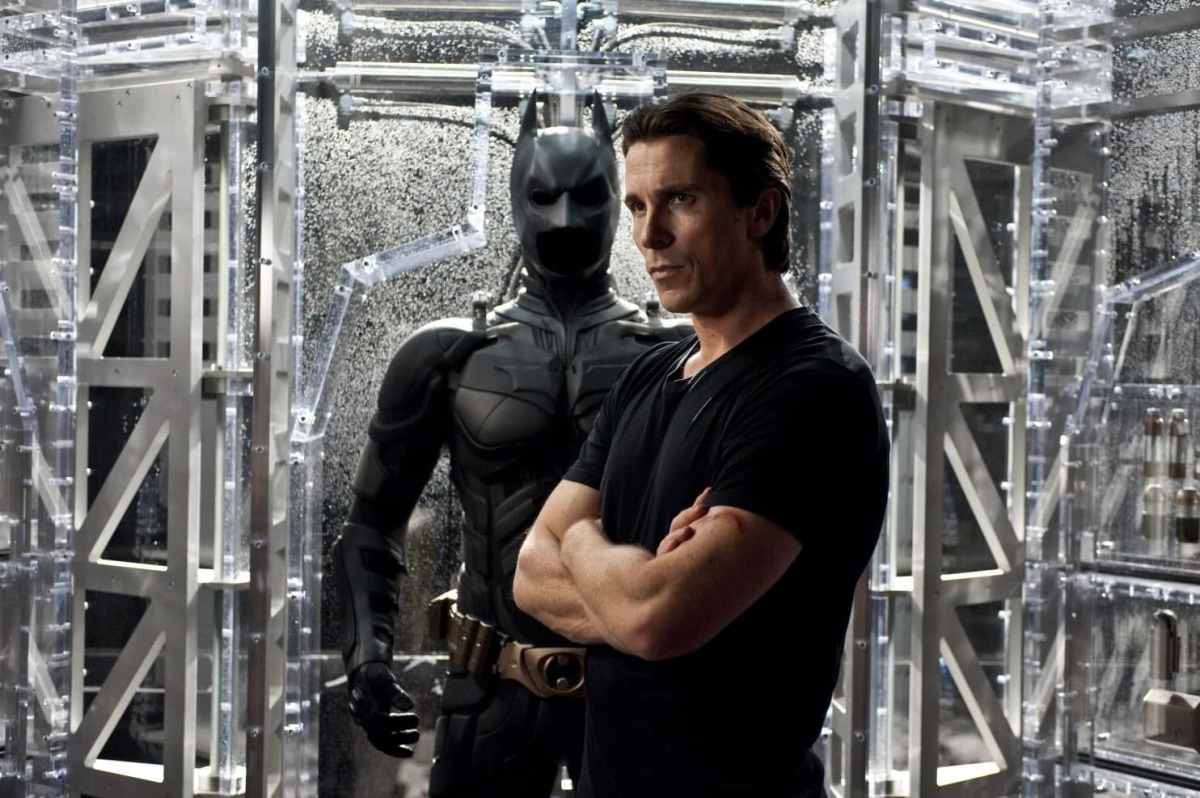

Bruce Wayne (Christian Bale) may only be a slight improvement. The decline of Gotham is at least partially down to Bruce’s neglect of his civic responsibility, allowing the charitable Wayne Foundation to go broke. Blake asks him to “start paying attention to the details.” Alfred (Michael Caine) insists that Gotham doesn’t need Batman. “The city needs Bruce Wayne. Your resources, your knowledge.” It is Bruce’s selfish decision to “consolidate” his power and wealth under one roof that allows Bane to take control of his resources and use them to seize the city.

Critics point to the army of police officers fighting to retake the city as evidence of the film’s reactionary politics. However, The Dark Knight Rises is hardly flattering in its portrayal of Gotham’s “bloated police force,” swapping the corruption of Batman Begins and The Dark Knight for ineptitude. Jim Gordon is exposed as “plenty dirty,” a liar and a hypocrite who failed his city. At the climax, Blake tries (and fails) to talk a police officer (Desmond Harrington) out of shooting at him for trying to help a bus full of orphans escape the city. The film is wary of established power structures.

Repeatedly in The Dark Knight Rises, Bruce argues that the idea of Batman is bigger than the billionaire himself. “Batman could be anybody,” he tells Blake. “That was the point.” Does Batman have to be “Bruce Wayne, billionaire orphan”? Are there flaws baked into that conception of the character? When Bruce tries to escape the Pit, he is told that he is being held back by his status as “a man from privilege.” He needs to shed and share that privilege to become a true hero.

There is a sense of symmetry to this. Bruce had to cast off his privilege to become Batman in Batman Begins, traveling the world anonymously and in poverty to understand a world beyond his sheltered experience. Nitpickers criticize the idea that Bruce could get from the Pit to Gotham in the 22-day window that the film provides, but that’s the point. Bruce took that journey to become Batman in Batman Begins, and he takes a similar journey to bid farewell to Batman in The Dark Knight Rises.

Ultimately The Dark Knight Rises offers something rare in superhero fiction: an actual ending. After all, even the other big “last Batman story,” The Dark Knight Returns, has spawned several sequels. The Dark Knight Rises gets to choose its ending, arguing that it is possible to build a different kind of Batman. So many superhero stories are built around power fantasies and privilege — it is fascinating to see The Dark Knight Rises take the character archetype apart and put it back together.

Much attention has been paid to Bruce’s appearance in the closing montage of The Dark Knight Rises, debating whether it is a dream. However, the final shot of the film is not given to Bruce. Guided by a GPS, Blake wanders into the cave. As he moves towards the center of the cavern, the ground begins to rise beneath him. The sequence cuts to black as he is pushed out of view. A title card: The Dark Knight Rises.

In the wake of an economic crisis that Ben Bernanke, the former head of the Federal Reserve, described as “the worst financial crisis in global history,” The Dark Knight Rises asks what it means to build a superhero movie around a billionaire. More “a child born in hell” than “a man from privilege,” Blake teases a new kind of Batman. Blake offers a Batman not insulated by class and wealth, one more in touch with the times. The Dark Knight Rises dared to build a better Batman.