There is a general sense that good voiceovers can elevate a game. We praise strong voice acting and note when the re-release or an update to a game adds new voiceovers. They can make games more accessible, immersive, and easier to engage with.

I share the sentiment, and yet I wish games offered the option to turn voiceovers off. Not turn down the voice volume, which can affect environmental and ambient sounds, but offer the choice to toggle voiced dialogue in the same way that most games have the option to toggle cutscene subtitles.

I don’t imagine this would have much use in action blockbusters. I don’t want to read Nathan Drake’s one-liners while dangling from a cliff, nor Scorpion’s “Get over here!” while spearing a guy across the screen. But I think there are instances where having to listen to voiced game dialogue, however well done, can undermine enjoyment.

In a lot of games, especially RPGs, dialogue and narration are presented in text boxes. Often these are out of sync with the voiceover: The text box pops up, and then a voice delivers the dialogue and in some cases the narration. For example, in Fallout 3 and its sequels, several lines of dialogue are presented in full while a character speaks them.

The average rate of speech in English is about 150 words per minute. The average reading speed is somewhere between 230-300 words per minute. That means many of us will read a text box faster than a voice actor will deliver it, and therefore many of us will either wait for the voiceover to catch up or skip parts of the voiceover altogether. Both outcomes are jarring and break up pacing and immersion.

One solution is to turn off text rather than voice. I do this in my replays of games like The Witcher III and Mass Effect, but on the first playthrough I worry that I might miss or mishear important information. And it’s not always possible anyway.

Another solution is to sync the text and the voice, so that text is printed on the screen at the speed a voice actor delivers it. The problem is there would still be dissonance between how fast the words are displayed and how fast we could read them. Think about how frustrating it is when you set the text speed too low in a Pokémon game and have to slow down your reading to match the text speed.

The simpler solution is to have the option to toggle voiceovers on and off. Granted, it would remove the enjoyment that comes from well-voiced dialogue, but it would also remove the dissonance that comes from reading speeds outpacing voiceovers.

Unvoiced game text also brings its own kinds of enjoyment, distinct from a well-done voiceover. The argument here is similar to the discussion about audiobooks versus printed books and e-books.

While there is substantial overlap between reading and listening in terms of the brain processes that are engaged and the comprehension outcomes, there are also many differences. The most obvious one is that written and voiced text cannot be interacted with in the same ways. A well-written piece of prose may cause me to pause reading to savor it or to re-read it to figure out how it’s structured and paced. Likewise, dense prose will prompt me to re-read it or read it slowly to ensure that I’ve understood it. This is markedly different from audio, which cannot be rewound or slowed down in games and often cannot be paused without skipping a chunk of dialogue.

A related point is interpretation. When we read something, we engage in a different kind of interpretative exercise than when we listen to it. We have paragraphs, punctuation, and other cues to aid us that are absent from audio files, but we have to imagine what the characters sound like and how they speak in a particular situation. As a result, just as we build up an impression of a character when we read a novel, so we do the same with an unvoiced game character.

In contrast, a voiced character forces us to share the developers’ and the voice actor’s interpretation of that character, and the two don’t always overlap. I am still disappointed by The Elder Scrolls Online’s portrayal of Vivec, for example. (In my head, after years of playing Morrowind, he is similar to the detached megalomania of Niander Wallace in Blade Runner 2049. In The Elder Scrolls Online he is voiced like a stuck-up, spoiled noble.)

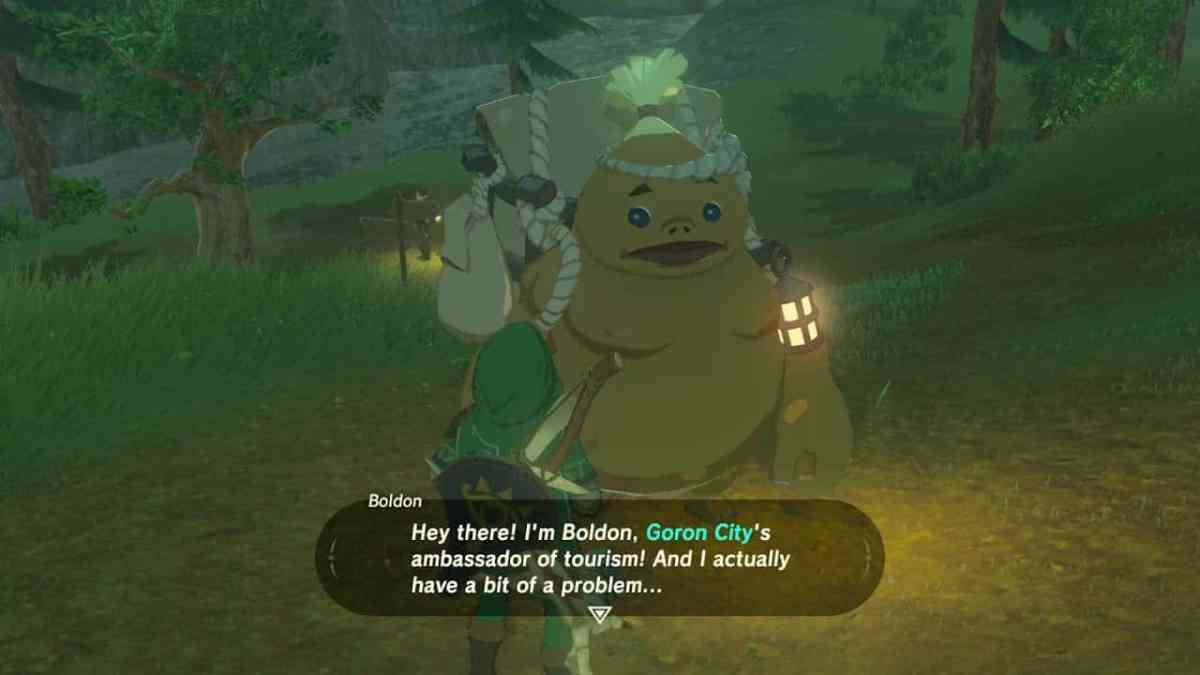

Likewise, unvoiced game text provides more opportunities for interaction. Paper Mario and Zelda games are great platforms to act out silly voices when playing them with children, similar to the way we might read books to children.

Indeed, The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild is a fine example of how much can be conveyed with minimal audio cues and text. The vast majority of its characters are unvoiced, but the combination of excellent art direction and a few basic but expressive sounds is enough to enable us to project a personality onto each bit of text.

In this way, Breath of the Wild is similar to indie and older titles, where the amount of voiceovers is limited by budget or storage medium. It’s the reason I’m ambivalent about the “Final Cut” of Disco Elysium, for instance. Thanks to the superb writing, I have formed strong impressions of many of its characters. A fully voiced update of the game is unlikely to match all of my impressions, whether that’s for better or worse.

The argument here isn’t that we need fewer games with voiceovers or to disparage the work of excellent voice actors. It’s just that sometimes unvoiced game text can work better than voiceovers, and it would be nice to have the option to switch these off as easily as we can switch off subtitles.