This discussion and review contains spoilers for The Last of Us episode 9, “Look to the Light,” the season 1 finale.

One of the big arguments about the video game version of The Last of Us concerns the importance of player agency within the narrative, specifically the ability of players to make choices that can affect the outcome of the game. This is particularly true of the ending, which “Look to the Light” adapts reasonably faithfully.

“The game doesn’t give you a choice,” noted Paul Tassi. Carol Pinchefsky docked the game’s review score in protest to the climax, which forces the player to kill a doctor who was armed only with a scalpel. “It rubbed some people the wrong way, that they didn’t have a choice, because — especially at the end of games — they’re so used to having this moral choice,” admitted the game’s co-director Neil Druckmann. It remains somewhat of a point of controversy among gamers.

While it frustrated gamers who were used to particular conventions within the medium, it served an important thematic purpose. It potentially forces a wedge between the player and the character, with Joel’s (Troy Baker) motivation potentially at odds with that of the person holding the controller. There is a dissonance there, one that plays with the particular strengths of video games as a medium, particularly in the way that they can make players culpable and complicit.

“It’s the contrast of the conflicts between what the player is thinking versus what Joel is thinking that allows you to explore what we’re doing with that character,” explained co-director Bruce Straley of the choice. “It’s because you’re not him that you get to see him.” As critic Danielle Riendeau observed, it’s a choice that puts the audience at a remove from Joel’s internal life, “You’re a participant in the story, but it is not your story to tell.”

It’s an approach that aligns with passive media like film and television. Indeed, consider how much outrage over the past few years has been generated by fans complaining that beloved characters like Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill) are “out of character” because they make decisions with which the viewer does not agree. Even then the audience doesn’t have any real agency with film or television, beyond the capacity to turn off or walk out.

So it is interesting to see that narrative translated to a television show and how well it plays in that format. Part of what is so impressive about “Look to the Light” is how intimate it feels, how measured and how personal. The first season of The Last of Us has a very interesting structure, with its biggest set piece playing out at the midpoint, with the assault on Kansas in “Endure and Survive.” Even the confrontation with David (Scott Shepherd) in “When We Are in Need” feels more “epic” than “Look to the Light.”

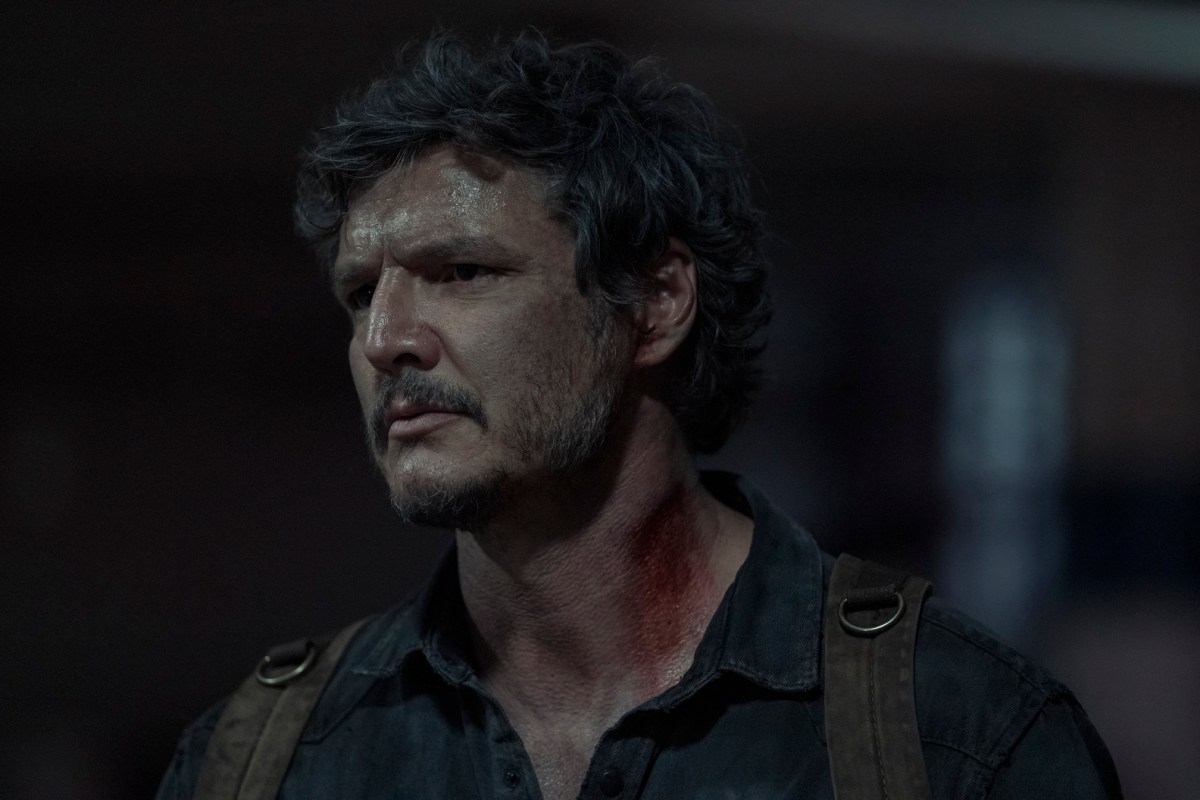

“Look to the Light” is the shortest episode of the season. It is two minutes shorter than “Please Hold to My Hand,” the only other episode to clock in with a runtime under 50 minutes, and that was an episode that was largely devoted to setup for “Endure and Survive.” It is just over half the length of “When You’re Lost in the Darkness.” It begins with a sizable time jump following the events of “When We Are in Need.” Joel (Pedro Pascal) is fully recovered. The seasons have changed. Ellie (Bella Ramsey) has almost finished her journey.

The first half of “Look to the Light” is disarmingly and decidedly low-stakes. The episode opens with a 10-minute flashback to Ellie’s birth and to the death of her mother, Anna (Ashley Johnson). When the episode does rejoin Joel and Ellie, Joel is thrilled to find some canned beefaroni and a copy of the board game Boggle. There is no real sense of dread or doom. Instead, something else hangs over the pair — the understanding that their time together may be coming to an end.

As ever, there’s a lyrical and poetic quality to the storytelling in The Last of Us, as Ellie finds and feeds a giraffe. It’s a moment of tenderness and innocence. As with the trip to the mall in “Left Behind,” it is a reminder that Ellie is still a kid, even if she’s been born into a world that won’t let her be one. At the end, the giraffe runs off. It gets to be with its family. The subtext isn’t especially subtle. Even Joel and Ellie ruminate on the looming end that awaits them.

Ellie is committed to seeing their journey through to its end, doing what she can to help find a cure or a vaccine for cordyceps. “It can’t be for nothing,” she tells Joel. “I know you mean well. I know you want to protect me — you have. And when we’re done, we’ll go wherever you want. Tommy’s, sheep ranch, the moon. I’ll follow you anywhere you go. But there’s no halfway with this. We finish what we started.” This makes sense. This is what Ellie wants. Of course, there’s a tension with what Joel wants.

When Ellie and Joel are captured by the Fireflies, Marlene (Merle Dandridge) explains to Joel that her doctor believes the key is the cordyceps that Ellie carries within her, which creates “messengers” that fight off infection. “He’s going to remove it from her, multiply the cells in a lab, produce those chemical messengers — and then we can give it to everyone,” Marlene explains. “He thinks it could be a cure, Joel. A cure.” There’s just one catch, as Joel points out: “Cordyceps grows inside the brain.”

Joel is naturally horrified by this. Marlene has not told Ellie that they are going to lobotomize or kill her. She will just go under anaesthetic and never wake up. Marlene orders for Joel to be removed from the hospital. Joel instead embarks on a killing spree through the hospital to rescue Ellie. He kills soldiers, he kills doctors, and he ultimately kills Marlene. He carries the unconscious Ellie out of the hospital. When she wakes up, he lies to her. “They’ve stopped looking for a cure,” he explains.

As shot by director Ali Abbasi, Joel’s attack on the hospital is brutal. It isn’t exhilarating or thrilling. It isn’t even cathartic. It is Hobbesian in a sense, “nasty, brutish, and short.” Gustavo Santaolalla scores the sequence to a version of the show’s theme that sounds like a mournful dirge. For most of the sequence, Abbasi shoots the violence in a way consistent with how The Last of Us has approached such brutality. The camera is largely focused on Joel. The audience is watching him.

It’s an effective and unsettling choice, because it firmly anchors the audience’s perspective on Joel, if not with Joel. The camera focuses on Joel’s face, on the gun that he holds in his arms, and on the bullet casings that hit the ground after each discharge. The first time the camera focuses on a dead body, it’s as Joel swaps his firearm. It’s haunting and harrowing, particularly given how Pascal plays Joel’s passive efficiency. Joel has made a choice and is acting on it. There’s nothing more to it.

Late in the sequence, Abbasi breaks with the visual conventions of the larger show. Towards the end of the firefight, “Look to the Light” finally allows the victims to come into focus. The audience sees the faces of these dead soldiers. They see the blood and the brain matter pooling on the ground near the doctor (Darren Dolynski). “Look to the Light” is asking the audience to sit in what Joel has done and to really confront and contemplate it. This is our hero. Why did he do this?

At the most basic, the answer is obvious. Joel did this to protect Ellie. When Marlene asks whether Joel is really willing to doom this “broken world,” he replies, “Maybe, but it isn’t for you to decide.” He’s technically correct. Ellie didn’t consent to the procedure. Marlene made that choice for her. Indeed, even if Ellie wanted to make that choice, there’s a question about whether she is old enough to make it. After all, many medical decisions involving children are ultimately made by guardians.

Joel’s decision is understandable, especially as Ellie’s surrogate father. The episode opens with a similar depiction of parental sacrifice. Anna is bitten while she’s giving birth to Ellie. Marlene finds her holding a knife to her own neck. She would rather kill herself than risk her baby. “How long have we known each other?” she asks Marlene. Marlene replies, “Our whole lives.” Anna responds, “So you pick her up right now, and then you kill me.” Anna gave her life for Ellie. Maybe Joel gave his soul.

Discussing the ending of the game, Druckmann has stated, “I haven’t heard a single parent say(,) ‘I disagree with Joel’s decision.’” There is perhaps something poetic in a parent placing the safety of their child ahead of the entire world. Given the Christian imagery in “When We Are in Need,” it’s revealing that Joel makes the exact opposite choice that the Christian God made with Jesus, refusing to sacrifice his child to redeem the world.

The beauty of “Look to the Light” lies in the lingering ambiguity. It is entirely possible that Joel didn’t make the choice for Ellie, but for himself. Tying back to that debate about player agency within a video game narrative, Joel didn’t just overrule the player. He overruled Ellie, removing her ability to choose. When Joel warns Marlene that it’s not her choice, Marlene replies, “So what would she decide, huh? Because I think she’d want to do what’s right, and you know it.”

Early in “Look to the Light,” it is made clear that Joel has embraced life thanks to Ellie. He confesses that he attempted suicide after the death of his daughter, Sarah (Nico Parker). “There’s no story,” he admits. “Sarah died, and I couldn’t see the point anymore. Simple as that.” He recalls, “I went to pull the trigger; I flinched, still don’t know why.” The implication is that Ellie had provided the “why” and the “point.” She muses, “So, time heals all wounds, I guess.” Joel replies, “It wasn’t time that did it.”

In the season’s final scene, Ellie admits frustration at how many people who died to get her to this moment. “That’s not on you,” Joel assures her. “Look, sometimes things don’t work out the way we hope. You can feel like… like you’ve come to an end and you don’t know what to do next. But if you just keep going, you find something new to fight for…” He’s not trying to convince her, but trying to convince himself. He talks eagerly about Sarah, making it clear he sees that connection, even as he awkwardly assures her they are “definitely different kids.”

There is a selfishness to Joel’s choice, his decision to hold on to Ellie for as long as possible. Marlene states the obvious. “You can’t keep her safe forever,” she warns him. “No matter how hard you try, no matter how many people you kill, she’s going to grow up, Joel. And then you’ll die or she’ll leave. Then what?” The Last of Us is a show about codependency, about the need to be needed. Did Joel make the choice for Ellie’s benefit or his own? Does that matter? Does Ellie know? Does he know that she knows?

“Look to the Light” ends with layers of ambiguity, its characters inscrutable to the audience and each other. It’s masterful storytelling.

If you enjoyed Darren’s The Last of Us reviews for the past couple months, then you’ll be thrilled to hear that he writes insightful commentary like this several times a week at The Escapist! Stick around and check it out!

Related: How Old is Ellie in HBO’s The Last of Us on We Got This Covered