There are franchises and then there are phenomena, and the difference is the latter can be a lot harder to explain. To properly articulate why the Kickstarter for a tabletop roleplaying game set in the adorable woodland world of the board game Root is so exciting is to be reminded that not everybody you know is as invested in the genre of high-medieval fiction that stars anthropomorphic rodentia.

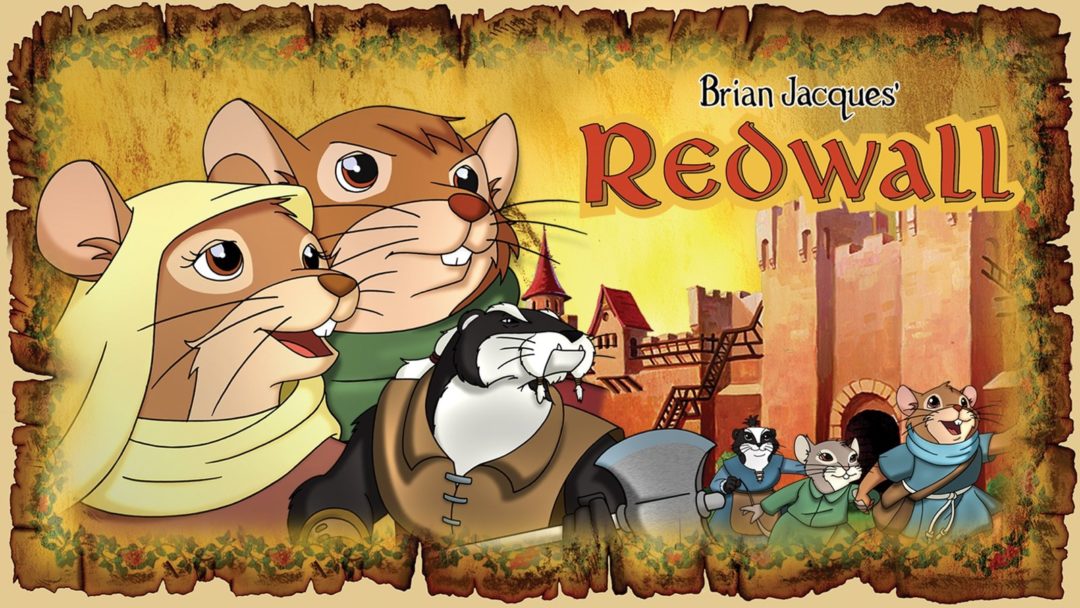

Already fully funded and rocketing past stretch goals, Root: The Tabletop Roleplaying Game is based on the deviously asymmetrical board game Root: A Game of Woodland Might & Right. It’s set in the woods and features various factions of anthropomorphized animals engaged in a medieval power struggle. The roleplaying game brings the narrative down to the ground level, giving players the means to create heroic characters in the style of a Dungeons & Dragons adventuring party. It is proudly and obviously inspired by the Redwall novels by Brian Jacques, without which it is hard to imagine anybody anywhere would be talking about mice, badgers, rabbits, and stoats running around with swords.

Yet those conversations are happening everywhere in the world of gaming. Ghost of a Tale is a stealth and puzzle-solving fantasy video game starring a mouse pitted against brutish rats. The RPG Mouse Guard, based on David Petersen’s comic series, is a medieval adventure starring “guardsmice” who valiantly patrol the borders and fight the dangers of the wilderness. Tabletop roleplayers are also looking forward to the forthcoming Humblewood, a setting for 5th Edition Dungeons & Dragons that gives players the ability to roll up anthropomorphic birds. It has raised more than $1 million on Kickstarter after initially asking for $20,000. Cute woodland critters embarking on epic adventure is a broader niche than it’s ever been.

That was when our Order found its true vocation. All the mice took a solemn vow never to harm another living creature, unless it was an enemy that sought to harm our Order by violence. They vowed to heal the sick, care for the injured, and give aid to the wretched and impoverished. So was it written, and so has it been through all the ages of mousekind since. – Redwall

The world of Redwall is one of mice, rats, stoats, foxes, rabbits, and every other conceivable sort of woodland critter who dresses, walks, talks, and acts like humans in a medieval society. Much of the series is set in and around Redwall Abbey. Though there are the occasional signifiers of humanity around, Jacques was adamant that humans would never figure into the stories. This can lead you down quite a (figurative) rabbit hole if you think about the stories too hard. Are the inhabitants of Redwall Abbey Christians? If so, how?!

Ignore that dull line of thinking, though, and the series is a straightforward fantasy adventure starring determined young heroes who wield magic swords and embark on perilous quests to the wilderness beyond the light of civilization and comfort. It’s a world where badger warlords defend their strongholds from invading armies, mercenary squirrels in tartans fight wolverines, and otters swear vengeance against their family’s killers. During the 25 years Jacques wrote the series, the world’s borders widened and the details of its history deepened until it stuffed to bursting. Jacques took roughly equal time penning descriptions of mouth-watering homemade food and badass fantasy violence.

The natural question somebody unfamiliar with the concept might ask is, “Why animals?” which is really to ask, “Why not humans?” The creatures don’t particularly act like real mice and rabbits, though the moles are really good at digging and somewhat nearsighted. I think the answer is very similar to why Samurai Jack usually fights robots that spew oil that is totally not blood when they’re bisected by his magic sword: The danger and gore are happening to characters that aren’t human. Redwall featured tales about armies of “Corpsemakers” and regular gruesome endings for bad guys that include beheadings and being flash-boiled to death. Jacques likely knew that when writing for kids he had a choice between actual, harrowing stakes or storytelling that pulled its punches to avoid imperiling young (human) characters.

Shorting those stakes would’ve been talking down to his audience. Kids responded to his more mature fare, and the ones who were wee tykes when the series debuted in 1986 have since grown up into a generation hungry to relive adventures in the same vein.

“I wrote it as a story to read to the children at the school. A mouse is the child, and the child is trying to resolve something, to be better, to be a warrior, to be a hero. If the little mouse can, well why can’t the child?” – Brian Jacques

If the Beatles are Liverpool’s most famous sons, Brian Jacques was probably its most dutiful. While he did leave at 15 to join the Merchant Navy, the author of Redwall returned before long and worked almost every job imaginable. He was a policeman, a dock worker, a member of a folk music band, and a milkman. That breadth of experience, and the holistic view Jacques had of workaday life, shines through in his books, with their sprawling casts of characters. While working as a milk deliveryman, Jacques also spent time reading to kids at the Royal School for the Blind in Liverpool and became dissatisfied with the book options.

“Some of the stuff, especially for the older kids, I didn’t like the stuff I was reading,” Jacques said of YA literature he encountered at the time in an interview with the BBC. “It was about the now, about the here, today: Divorce, problems with the family, teenage angst. What happened to the magic?”

Jacques took matters into his own hands and wrote what would become Redwall. He read his work to the children at the school, taking care to be as descriptive as possible considering his audience. A friend got his hands on the work and insisted Jacques submit it to publishers, who then asked him for five more books. Jacques wrote 23 books in the series between the publication of Redwall in 1986 and his death in 2011.

The Abbot’s old face broke into a weak smile.

“My old friend, I am not like the seasons. I cannot go on forever. It has to finish sometime.” – Redwall

Readers might be drawn into the series by the tales of brave mice who use bemusing words like “everybeast” for “everybody.” But the comforting sense of place and time are what keep readers committed, and what I think inspire so many creators to try to carry Redwall’s torch. The original novel feels like it should be read out loud. Each character’s voice is distinct. By casting animals as his heroes and villains instead of humans, Jacques gives his intended readers a kind of safe remove from things. He assured them that even amidst attacks by venomous snakes who code as dark gods or sieges by cruel rat hordes, things will all work out for the plucky heroes.

Jacques gave the novels the same rough, plainspoken warmth that he projected in interviews. An animated series adapting Redwall featured a live-action Q&A with Jacques at the end of episodes, and in one segment he was asked whether he’d ever stop writing Redwall novels. He assured viewers that as long as they kept reading them, he would keep writing them. They did, and he did. After 20 million books translated into 28 languages, his last Redwall novel, The Rogue Crew, was released posthumously in 2011.