This article contains early-to-mid-game spoilers for Pentiment in its discussion of time as a narrative device.

In Pentiment, the callousness of time, its disregard for the wants and whims of humanity, first struck me at the end of the first act. I had just played a key role in condemning a man to death for a crime that I was never convinced he was guilty of, all in the name of saving another man from the executioner’s axe. The game forced my hand, but at least Brother Piero was spared…

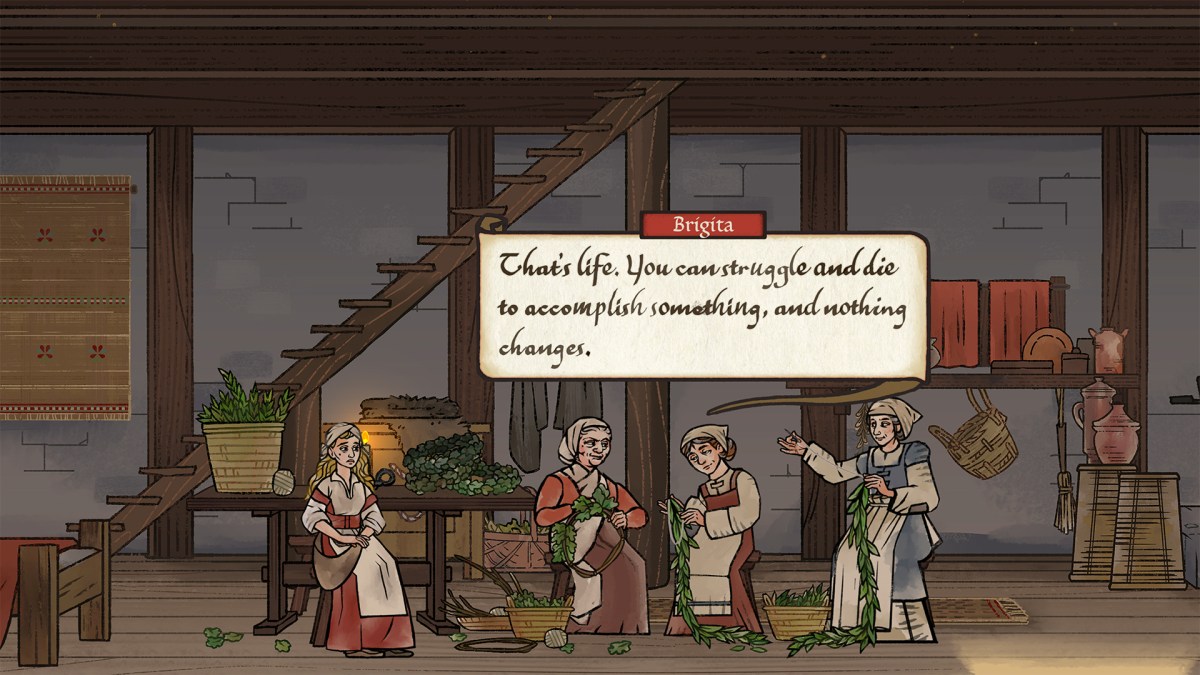

In many other stories, that would be the end. A brief denouement would follow; the accuracy of my pointed finger would be laid bare, and the twin communities of Tassing and Kiersau would find a new normal in the aftermath of chaos. Not so in Pentiment.

Instead, for us as players, seven years pass in the blink of an eye. It’s a classic example of juxtaposition. One second, our hero Andreas speaks with Brother Piero about the promise that the future holds. The next, he stands by a gravestone — clearly older — lamenting a friendship that withered like a plant in the darkness. The sudden shift is a gut punch. In a moment, we see the cruelty of time laid bare: Andreas as a hopeful (if uncertain) youth, Andreas as an embittered adult.

I knew it was coming. The decades-spanning story was a fixture of Pentiment’s pre-release marketing, but that didn’t make that juxtaposition any less of an emotional bludgeon. The focus on an unfulfilled friendship in that moment brings with it a considerable amount of baggage, none of which inspires happiness.

The transition between time periods isn’t just about making us feel bad, though. It’s also about inspiring reflection. It emphasizes how the very concept of time is one of the main themes of Pentiment.

The first impression is that time is tyrannical.

It’s not only robbed Andreas of his joie de vivre, but it’s also already robbed the player of the truth. You can find what may be incriminating evidence as you work to solve the first murder, but the potentialities pull you in different directions. It could just as easily be a monk, a peasant, or the widow who lives on the outskirts of town. You’re challenged to chase several threads, but talking to people takes time. Everything is an exchange: your effort for their information. There are only so many tasks you can fit into one day, and the imminent arrival of the archdeacon makes it impossible to uncover every clue.

And even if you could, there’s a sense of misdirection. In classic mystery story fashion, Pentiment takes pleasure in misleading the player. The breadcrumbs are spattered about, but there’s no smoking gun — and at a higher level, there’s the mysterious figure who Andreas comes to call the Thread-Puller. With everyone baying for what passes for justice in this unfair world, you simply don’t have time to explore the larger mystery.

In the moment of judgment, this narrative design breeds tension. How much do you say about each suspect? Do you mention your belief in a greater conspiracy? But above all, which resident will you commit to death?

We recognize that manipulation as we play, but it’s only after the time skip, only after we see how Andreas has been jostled by the rigors of time, that we realize all of it was a trap. Why did we make the decision? Why did we fight to condemn someone else who (as far as we can tell) was innocent if death and pain was all that waited?

Yeah, time is a tyrant. And yet…

The second impression is that time is tender.

With its time skips that span decades, Pentiment taps into the tradition of stories like Ken Follett’s The Pillars of the Earth and Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. As in those books, the passage of time proves to be illuminating. It explores how fortunes and attitudes change across generations. It shows off the butterfly effect of how small decisions can shape and reshape life itself.

It’s a narrative tool that can show off life at a macro scale — and Les Misérables does so beautifully in the way it follows Jean Valjean from desperate thief to upright citizen to adoptive father to hero. Even more potent is its ability to focus on the little things, which is the approach Pentiment takes.

The first Tassing resident you meet in the game is Ursula, who starts off as an adorable little dumpling. She’s a toddler at the time of Andreas’ first visit, so your interactions with her are barely interactions at all. She can’t speak, so her speech bubbles are filled with strings of letters that vaguely resemble her intentions. Seven years later, she’s a young girl, curious about the world, and you have the chance to shape a little bit of how she sees things. Many years later, she’s a young woman embarking on the next phase of her life.

In that, Pentiment reminds me of watching from afar as my niece and nephew grow up. I see them only rarely — sometimes with years between our catch-ups — and it never ceases to amaze me how much they change over time. I remember them in snapshots: as toddlers, as kids, as rebellious adolescents. I see their lives as slideshows.

The gaps in Pentiment are much larger of course, and the compression of time is far more intense. That turns it into a treat. There’s a lot more than just seeing kids grow up. A disreputable youth reforms and becomes a sensible community member. A peasant rises to have a central voice on the local council. Technology moves on, and secularism rises as a counterpoint to religion. You see how the changes affect the lives of the people in this small, tight-knit community — for the worse, yes, but also ultimately for the better.

The final impression is that time is total.

Thanks to its unique scope — a small world with a large time span — Pentiment makes you feel less like Andreas and more like an unseen member of Tassing’s community. You sympathize with those who suffer under the yoke of heavy taxes. You feel for the young people with their crushes and the weight they carry from the choices of their parents. You see joy and pain, love and sorrow, fear and fury. You see life.

As I write that, I’m reminded inexorably of 2018’s God of War, which also aimed to showcase a broad array of emotions. I’m thinking particularly of Atreus’ arc, wherein his godhood inspired arrogance before he eventually came to terms with what Kratos was trying to teach him. It feels coherent until you realize that the absence of cuts means everything is happening in real time. Everything that happens happens in mere hours, which undercuts the emotional resonance it carries.

That’s not meant as a complaint. Instead, it’s a statement about how texts can communicate. Just as Dark Souls and Elden Ring have shown the potential for a different path in video game storytelling, so too does Pentiment. It’s not necessarily as bold, but any willingness to do things differently offers new ways of thinking.

In Pentiment, that takes the form of viewing time as a character. By influencing how players feel, being an object of curiosity for the characters, and enabling changes to the setting, time has a profound influence over the game. It’s not much of a revelation, but it’s certainly more refreshing than having time as nothing more than a metric.