More than eight years since Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell: Blacklist and after years of rumors and cameos, a remake of the original Splinter Cell is on the way. After such a long time in the dark, it’s an opportunity to reintroduce the franchise and revisit what made Splinter Cell a must-have title for the original Xbox back in 2002. Stealth gameplay based on dynamic shadows, cover, and sound, with elements of light platforming, thermal and night vision, lock picking, multiple gun attachments and gadgets, dropkicks, human shields, and rappel-line infiltration and shootouts – Splinter Cell combined a host of refined and new gameplay features in an attempt to offer a hyper-realist, gritty answer to stealth genre founders like Metal Gear Solid, Tenchu, and Thief: The Dark Project.

In this context, the use of the Tom Clancy license was a no-brainer. Besides the obvious commercial potential of the wildly popular license, Clancy’s fiction was known for its preoccupation with cutting-edge military technology, state espionage, and overly competent field agents – the ideal fit for a game about a deniable agent equipped with the latest technology to retrieve military information from behind enemy lines without being seen.

Nearly two decades later, a natural question is whether the old Tom Clancy setting is still relevant. The most obvious technological changes in the last two decades, of course, are the advent of broadband internet, smartphones, and social media. Around the time Splinter Cell released, only one in 10 households in the UK had access to broadband, for example. The first iPhone was five years away. And while there were a number of instant messaging services available for PC, Facebook would not come into being for another two years. In such a world, the idea that a man clad in military-grade spandex might rappel down the side of a building to steal a hard drive from foreign soil was not too difficult to imagine.

Today, state espionage and interference is just as likely to be conducted through social media manipulation, remote smartphone hacking, and drone flights. It’s something that later licensed Tom Clancy games, not least Splinter Cell: Blacklist, have worked into their fictions.

The other major change is the political climate. It would be impossible to capture 20 years of global politics here, but to put things in perspective, it might suffice to list some of the relevant milestones. In 2002 we were just one year into the George W. Bush administration, a year into the War on Terror, and a year before the Iraq War. It was also around 10 years since the collapse of the USSR, which led to widespread political, economic, and social instability in former Soviet regions, including regime changes, civil war, and military conflict in Georgia, that did not stabilize until the early 2000s. The positioning of the climate crisis as the most pressing problem of the modern age, the 2008 financial crisis, the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations, rapid economic growth in China, and two years in the grip of a pandemic were either unimagined or unimaginable.

And so I boot up the original Splinter Cell for the first time since it released, prepared to be greeted at every turn by an outdated setting and plot. Imagine my surprise then as I watch a fake news broadcast announcing the assassination of Georgia’s president by separatists, seizure of power by an industry oligarch, and problems for Georgia’s “hopes of integration into Western institutions.” A few missions later, another broadcast announces a Georgian invasion of Azerbaijan and a NATO retaliation led by the United States. Georgia responds by launching a wave of cyber terrorist and information warfare attacks on the US, supported in part by renegade Chinese military and a Russian ex-Spetsnaz operative.

The world of Splinter Cell might not know the horror of Zoom meetings or unboxing videos, but there are some surprisingly relevant and unnerving parallels to be drawn with the present day. Indeed, make a few adjustments for the names of countries and state figureheads, and the resemblance to the current political climate is uncanny. Similarly, the technological aspects are not as dated as they might first appear. Sure, the discussion of “bringing high-speed fiber optic connectivity to areas of Eastern Europe” in that first fake news broadcast is quaint, but several missions involve wetwork that presumably has no modern digital analogue. In the game’s first non-tutorial mission, for instance, protagonist Sam Fisher is assigned to locate two missing CIA operatives, who later turn up dead.

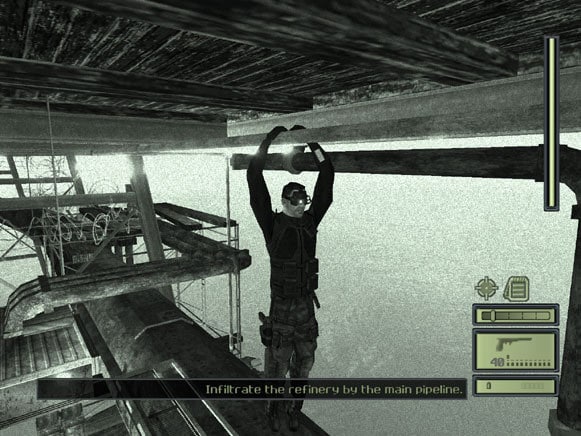

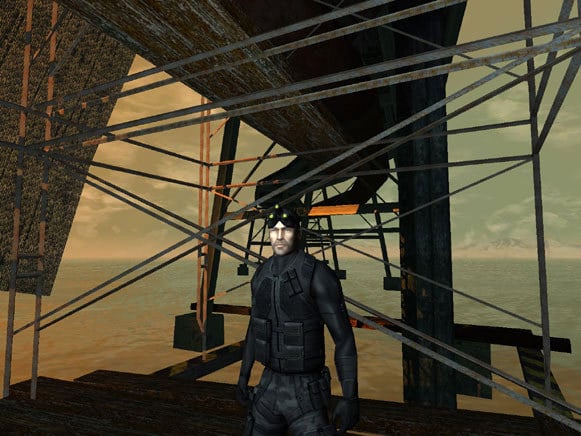

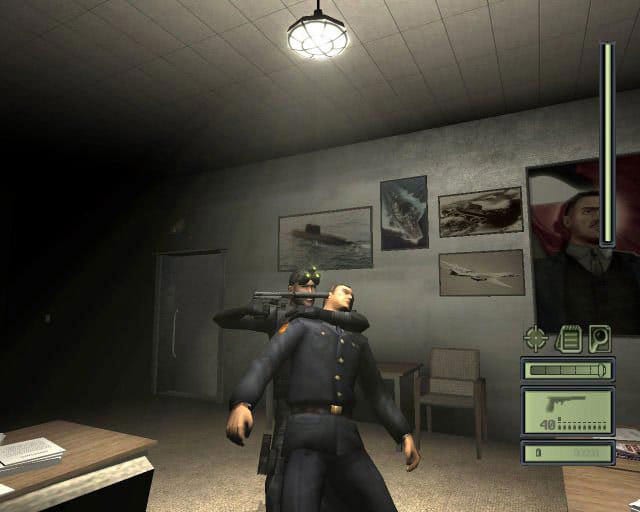

Likewise, the gameplay remains surprisingly fresh. Of course, that may be because, along with Metal Gear, Splinter Cell popularized a number of stealth and action staples still seen in games today. There is the ability to peek under doors to scout the area, to use shock, EMP, gas, and rubber ammunition to stun enemies and temporarily disable or destroy security cameras, the choice to knock enemies out or kill them and move their bodies, and to grab enemies and use them as human shields. There is also navigation enhanced by thermal and night vision goggles, plenty of hanging off pipes and ledges, and a robust lock-picking mini-game that involves working a tumbler to raise individual lock pins.

While Splinter Cell’s levels were much smaller and more linear than those on offer in stealth contemporaries like Thief or Deus Ex, they were elevated by heightened attention to detail that was unusual for the time. Each of Fisher’s actions, from his pull-up onto a ledge to his attaching a rappel line to his suit, is meticulously animated. Shadows respond realistically to light sources, cloth flaps in the wind, and offices are full of clutter, including several objects that were designed with an almost obscene eye for realism. There are more subtle touches too. Thermal vision goggles can be used to check which buttons were recently pressed on a keypad to figure out the code, for example, but wait too long and the heat signature will fade.

If anything, it might be Splinter Cell’s overall framing, rather than specific story beats or its gameplay, that dates it. There is an argument that the US has now moved beyond interventionism, i.e., the practice of direct interference in foreign affairs. In contrast, Splinter Cell is premised entirely on US interventionism – Sam Fisher exists to enable a US government agency to infiltrate, extract, and execute foreign (and on occasion domestic) policy with complete deniability. There are several missions in Splinter Cell for which Fisher’s handler does not have official authorization and are carried out extra-legally, if not outright illegally. The narrative implies that the ends justify the means and that often unnecessary bureaucracy stands in the way of necessary direct action.

That the Tom Clancy license would lean on conservative ideas should not come as a surprise – Clancy was a staunch Republican, after all. I imagine it may be possible to interpret Splinter Cell as a commentary on interventionism, a description of a certain approach to policy rather than as an endorsement of it. Admittedly, it’s difficult to see how this would be done. Fisher’s actions eventually avert a nuclear war, and the ticking bomb scenario is a notorious device for defending extreme measures to avoid an apparently greater disaster. However, even if it could be done, it would miss the point.

The interesting question here isn’t whether Splinter Cell is best seen as a commentary on or an endorsement of interventionism. The interesting question is whether that narrative is relevant at all. If the Splinter Cell remake can find a way to interrogate this while staying true to the original, it could become one of the most subtle takes on the Tom Clancy license in history – perhaps the only subtle take on the license, given the competition includes the likes of an allegedly Soviet submarine captain with a Scottish accent.