Kinji Fukasaku’s adaptation of Koushun Takami’s novel Battle Royale was perfectly timed. It coincided with the wave of international success for Japanese genre cinema following the breakout of Ringu. The film’s story of a bunch of teenagers trapped on an island and forced to murder one another became a cult classic, as well as a point of reference for a wave of young adult books and films over the next decade or so: The Hunger Games, The Maze Runner, Divergent.

Of course, the premise of Battle Royale was not necessarily original. Hunger Games author Suzanne Collins claims that the premise of her books was an update of the classic story of how Athens would sacrifice groups of children to the Minotaur on the island of Crete, positioning her heroine Katniss Everdeen as “a futuristic Theseus.” It’s also possible to draw a line connecting Battle Royale to William Golding’s classic novel Lord of the Flies.

In the 1980s, movies like Red Dawn and War Games found teens playing war. These stories of teen warfare evoked the memory of Vietnam, a conflict associated with the loss of a generation of young men. The 1982 documentary Vietnam Requiem claimed the average age of a soldier in Vietnam was 19, inspiring Paul Hardcastle’s 1985 hit. Other sources claim the average age was actually 22, but that is still four years younger than the average age of a soldier during the Second World War.

In the years since the release of Battle Royale, the imagery of children thrown into Darwinian struggle has only become more ubiquitous. Even beyond the young adult film franchise boom, the film’s premise was evoked by the “controversial and groundbreaking” reality show of “questionable legality,” Kid Nation, and the CW show The 100. The comic series Avengers Arena doesn’t hide its influences, with the villain boasting of stealing the idea from “a couple of kids’ books.”

However, 20 years after its original release, Battle Royale towers over much of the media that seems to have been constructed in its own image. This is perhaps most obvious with The Hunger Games, the young adult book series that became a young adult film series, sparking a revolution in book-to-screen adaptations following the success of the Harry Potter franchise. The Hunger Games is one of the cultural touchstones of the new millennium, but it cannot escape Battle Royale.

Again, writer Suzanne Collins has stated repeatedly and clearly that The Hunger Games was not directly inspired by Battle Royale. “I had never heard of that book or that author until my book was turned in,” Collins has stressed. This remains a matter of heated debate, but there’s no reason Collins cannot be taken at her word that her novel originated in the juxtaposition of “reality television programs and actual footage of the Iraq War.”

Parallel evolution can happen, even in pop culture; compare Volcano and Dante’s Peak in 1997, Armageddon and Deep Impact in 1998, even The Prestige and The Illusionist in 2006. Sometimes, these overlaps are subject to conspiracy theories and speculation that can set fandoms against one another, as with the parallel evolutions of The X-Men and Doom Patrol or Babylon 5 and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. However, they may also just speak to similar ideas drifting in the zeitgeist.

Still, even if the influence was not direct, it’s hard to separate Battle Royale and The Hunger Games. (Indeed, Battle Royale’s American Blu-ray release was scheduled to coincide with the theatrical release of The Hunger Games.) Given the influence of The Hunger Games on the wave of young adult film franchises that followed – including The Maze Runner and Divergent – that draws a large swath of popular culture into conversation with Battle Royale. The comparisons favor Battle Royale.

There are a couple of key differences between Battle Royale and the subsequent boom in stories of children murdering children. The most obvious is the level of brutality. Battle Royale is a staggeringly brutal film, one that is never afraid to show the actual physical violence that its characters inflict on one another. Not only that, the film emphasizes this brutality in contrast to the perceived innocence of its child and teenage characters.

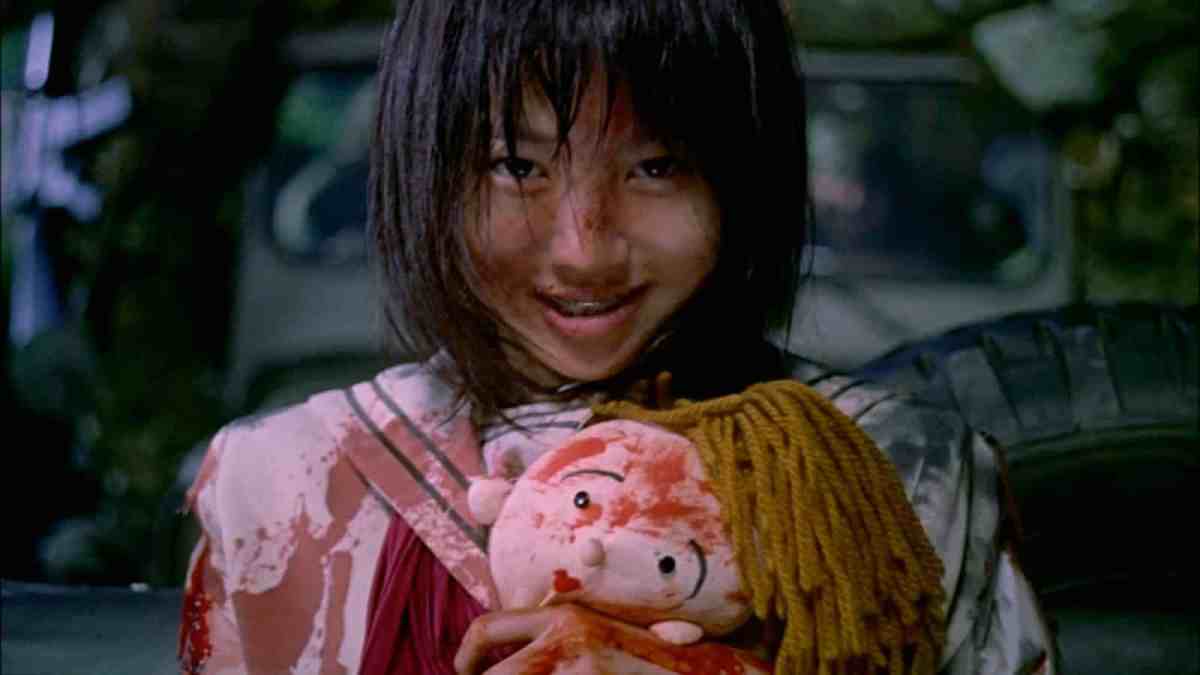

Most of the characters remained dressed in their school uniforms, a constant reminder to audiences that they are children. Blood flows freely, often from arterial wounds opened by their explosive collars. Overseer Kitano (Takeshi Kitano) graphically executes a couple of students during the briefing before the event starts. The film’s opening scene depicts the winner of the previous game, a young girl holding a teddy bear and covered in blood. “She’s smiling!” gasps a reporter.

It is refreshingly and horrifyingly unsanitized, especially when contrasted with the films that would follow. The home media edition of Battle Royale opens with a narration that reminds viewers of the age restriction and advising discretion. Battle Royale refused to make cuts to ensure a lower age rating, even as Fukasaku famously advised teenagers that “you can sneak in. And I encourage you to do so.” Battle Royale refused to condescend to teenagers, to temper the horror of its premise.

In contrast, The Hunger Games is a shockingly sanitized depiction of child murder. Acknowledging that the concept of “kids killing kids” is “a potential perception problem in marketing,” the film toned down its violence. It cut seven seconds to get a 12A rating in the United Kingdom. The result was a film that offered “sexless romance, pain-free violence.” Critic Joshua Rothman noted that “a key to the film’s success is that it only flirts with real violence, pain, and outrage.”

The Hunger Games exists in a market where horrible acts of violence are sanitized to make them palatable to ratings bodies, to ensure maximum marketability. As Kyle Buchanan observed, the system was often arbitrary: “Two to three uses of the F-word would ensure that a film received an R-rating, while a PG-13 movie could contain ten times as many murders.” The year after The Hunger Games, World War Z earned a PG-13 rating by keeping its zombie-apocalypse relatively bloodless.

“What people want now is violence that is clean and quick, provoking no questions,” lamented James Orbesen, discussing the PG-13 remakes of RoboCop and Total Recall. The murder of children in The Hunger Games is a neat affair, most obvious in the delicate passing of the film’s youngest child combatant, Rue (Amandla Stenberg). This carries through into other franchises like The Maze Runner. Characters can use firearms and trucks as weapons, so long as they do not draw blood.

The violence in Battle Royale is horrifying, as it should be. It is unsettling and uncomfortable, particularly as the film confronts audience members with the truly horrific choices that many characters make in the heat of the moment. It is traumatic. It inspires revulsion at a culture that would do this. In contrast, the action of films like The Hunger Games is thrilling and exciting, often asking the audience to get as swept up in the carnage as the viewing public in the film itself.

This gets at another interesting distinction between Battle Royale and the young adult dystopian fiction boom that followed. Stories like The Hunger Games, The Maze Runner, and Divergent are explicitly post-apocalyptic. They exist in a world clearly removed from the present, often by cataclysm and collapse. In contrast, the world of Battle Royale feels much more anchored in contemporary realities.

Battle Royale was obviously inspired by contemporary anxieties in Japan, particularly around youth violence. Even outside of high-profile cases like the Kobe child murders in 1997, there was a clear fear about the next generation. By October 1999, The New York Times reported that “youth crime (was) one of the fastest-growing criminal categories in the country.” Those fears simmer through Battle Royale, in characters like Kiriyama (Masanobu Ando) and Mitsuko (Kou Shibasaki).

However, the decaying culture of Battle Royale is not comparable to that of The Hunger Games. The film’s closing scenes and flashbacks suggest a recognizable Japan. The social collapse is driven by high unemployment and social disengagement. Indeed, Battle Royale repeatedly emphasizes that the horrors of the island are only an escalation of the norm, from Noriko’s (Aki Maeda) memories of bullying to Niida’s (Hirohito Honda) creepy obsession with Takako (Chiaki Kuriyama).

Battle Royale spoke to a Japan that was emerging from a “lost decade,” with the 1997/1998 recession seeing a spike in suicide rates among young people. It is about a generation “deprived of the means of survival in the new economy.” The island is a metaphor for what society expects from these kids. As Kitano summarizes, “Life is a game. So fight for survival – and find out if you’re worth it.” Mitsuko acknowledges, “No one is going to save you. That’s just life.”

Battle Royale is a film that understands that teenagers are often thrown into a brutal and bloody world that denies them the comforts afforded their parents while offering impossible odds against success. Indeed, what little the audience learns of Kitano suggests that he is a bad parent, while Noriko regretfully concedes that she will never get the life her mother had. Unlike many of the films that followed, Battle Royale doesn’t pull its punches in its exploration of adolescent horror.