Venom feels like a superhero movie displaced in time, arguably more of a piece with the superhero cinema of the 2000s than with the modern comic book movie landscape.

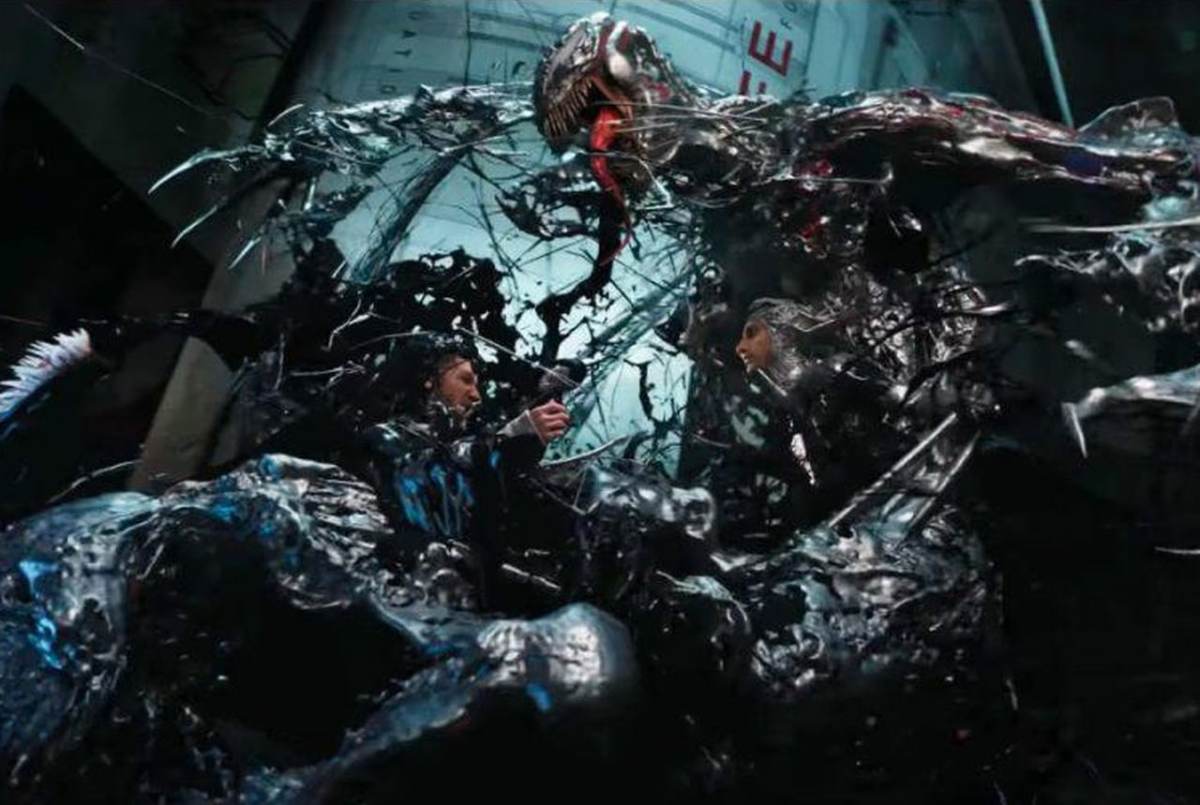

Venom is not a good movie. Ruben Fleischer’s action sequences are chaotic to the point of feeling disjointed. Jeff Pinkner, Scott Rosenberg, and Kelly Marcel’s screenplay would struggle to reach the basic level of “competent.” The plot is a collection of generic clichés. The characters are thinly drawn. The editing borders on incoherent. The climax devolves into a sequence that could charitably be described as a scene of two Cadbury Creme Eggs doing unmentionable things to one another.

However, there is something strangely compelling about watching Venom in an era where so many blockbusters rigidly adhere to the same template. Venom is particularly interesting as a blockbuster built around an established Marvel Comics character, produced by a studio other than Disney. Venom was produced by Sony, as part of the studio’s continued efforts to build an expanded universe around its licensing of the Spider-Man brand.

Sony released Venom eight months before 20th Century Fox released Dark Phoenix. In that gap, Disney announced that it was acquiring Fox — a business decision that would inevitably return control of the X-Men license to Marvel Studios. In ways that felt weirdly prophetic for a movie written and produced before the merger was announced, Dark Phoenix played out as a metaphor for that transition. It felt like the X-Men were trapped in a generic modern superhero movie.

In contrast, Venom is something altogether odder. It feels like a throwback to the kind of superhero blockbusters that were being produced at the turn of the millennium, when the success of movies like Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man or Bryan Singer’s X-Men had demonstrated that these movies could be viable, but the genre had yet to solidify around a single template. It led to an explosion of weird and unusual superhero movies that were frequently awful but occasionally fascinating.

Venom feels like a product of this millennial superhero boom in a number of ways. Many of these are entirely superficial. Notably, Venom featured a rap theme song from Eminem. While movie soundtracks may be making something of a minor comeback, it’s still relatively rare for a modern live-action blockbuster to have a theme song. While Eminem is still among the bestselling artists of the past decade, he was the best-selling artist of the first decade of the 21st century.

While modern superhero movies like Black Panther, Guardians of the Galaxy, and Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings do have tie-in soundtrack albums, Eminem’s theme song recalls the use of Nickelback’s “Hero” in Spider-Man or Evanescence’s “Bring Me to Life” in Daredevil. On an even more superficial level, Venom runs a tight 92 minutes from the company logos to the start of the closing credits, a sharp contrast to modern bloated blockbusters.

The film’s action sequences feel similarly old-fashioned. They are cut together in a choppy manner that is much closer to the rhythms of 2000s action movies than modern blockbusters. Venom basks in slow motion, whether during the movie’s central car chase or its climactic showdown. There’s something impressively low-tech about a chase sequence that finds Eddie on a motorbike being chased by explosive drones that could have been ordered from Amazon.

There are other markers of the era. Eddie Brock (Tom Hardy) would hardly be convincing as an investigative journalist at any point in American history, but the free-wheeling motorbike-riding host of “The Brock Report” certainly feels like an artifact of pre-recession depictions of the industry. Similarly, Eddie’s initial difficulty convincing an obnoxious neighbor to control their noise level, only to swiftly deal with it after he becomes a superhero, recalls a similar plot beat in Catwoman.

The villain of Venom also feels like something of a throwback. Riz Ahmed plays Carlton Drake, a billionaire industrialist who is up to no good. He spends most of the movie skulking around atmospherically lit office sets while delivering exposition to his minions until it’s time to throw down with the hero, recalling a specifically retro movie supervillain archetype, like the Kingpin (Michael Clarke Duncan) from Daredevil or Laurel Hedare (Sharon Stone) from Catwoman.

However, the clearest point of connection between Venom and turn-of-the-millennium superhero movies is a willingness — perhaps even an enthusiasm — to play fast and loose with comic book lore. After all, many of the early entries in the comic book movie boom took certain dramatic liberties with their source material, from small changes like Spider-Man’s organic web-shooters to larger changes like whatever was happening with the mythology in Catwoman.

Venom has to take considerable liberties with the source material. In the comics, Venom is inexorably tied to the character of Spider-Man, with the symbiote bonding with Peter Parker before finding its way to Eddie Brock. The broad strokes of this origin are covered in Sam Raimi’s misguided-yet-fascinating Spider-Man 3. Oddly enough, Venom decides to bypass the character of Spider-Man altogether, perhaps because the film was initially conceived as an R-rated release.

This is a big deal. The entire concept of Venom derived from the visual of Spider-Man in a cool black suit. This isn’t equivalent to imagining the Joker without Batman or Wolverine without the X-Men. It’s more like trying to imagine Reverse-Flash without the Flash or Bizarro without Superman. It is a fundamental reworking of the character — the kind of radical outside-the-box thinking that would do something like removing the mouth from a character known as the Merc with a Mouth.

There are times when Venom feels like it was a film pitched by an executive who had only seen a single illustration of the character mere minutes before the meeting. It’s an approach that doesn’t really fly these days, and that is probably for the best. Still, while the film never really coheres into anything particularly satisfying, there are individual elements of Venom that hearken back to what made so many of the early modern wave of superhero movies so fascinating.

Most obviously, Venom is a star-driven movie in a way that few modern superhero blockbusters allow themselves to be. Modern comic book movies don’t really tend to be built around movie stars. Actors like Chris Hemsworth and even Robert Downey Jr. have struggled to open movies outside their franchises. Tom Hardy’s performance is the best reason to watch Venom. Forget the lackluster action; the film’s best scene is Tom Hardy unleashed (and improvising) in a fancy restaurant.

This feels like a nostalgic throwback to the era when Oscar winners like Nicolas Cage and Halle Berry were headlining movies like Ghost Rider or Catwoman. It recalls how so much of the buzz around Daredevil focused on its leads, whether Colin Farrell’s infamous sex tape or Ben Affleck and Jennifer Garner’s onset romance sparking Bennifer: The Sequel. (As is the way of things, it appears that Affleck and Lopez have reunited for the inevitable Bennifer: The Nostalgic Reboot).

Building from that, Venom foregrounds its central romantic relationship in a way that few modern superhero movies do. The film is actually and earnestly invested in the relationship between Eddie and his former fiancée Anne (Michelle Williams). Eddie’s big moral transgression is a betrayal of Anne’s trust, breaking up their relationship. His big moment of emotional catharsis is an earnest apology to Anne for that betrayal. (“Aw,” Venom sighs, “that’s nice.” It is nice).

Superhero movies used to place a similar emphasis on interpersonal romances, but they are largely absent from modern iterations of the genre. Perhaps the best example is the relationship between Peter (Tobey Maguire) and Mary Jane (Kirsten Dunst) in Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man, which hinges on similar dynamics. Mary Jane spends much of Spider-Man 2 trying to trust Peter, and Peter spends much of the movie caught between his own sense of obligation and his love for Mary Jane.

Much has been made of how the modern superhero genre is weirdly sexless, particularly given how aggressively it fetishizes perfect physical bodies. This wasn’t always the case, and so Venom’s willingness to get weird is something of a throwback. At one point, Eddie and Anne pass the symbiote through an intense physical embrace that has fairly explicit undertones. (The subtitles helpfully articulate the subtext: “Eddie moaning,” “Anne grunts,” “gasps softly.”)

Venom is a bad movie. However, it’s also an interesting one. It offers a strange and dysfunctional throwback to the early wave of modern superhero films, standing in stark contrast to contemporary examples of the genre. In some ways, it shows how far the genre has come in the past decade or so. In others, it suggests what has been lost. Watched today, it feels like an alien from a completely different world.