A version of this review for Virtual Boy Works was originally published at Nintendo Enthusiast, now defunct.

Virtual Boy is the worst hardware disaster that Nintendo has ever had, and the average video game enthusiast doesn’t know much more about the console than that. And although it’s an accurate assessment, it also glosses over so many things that were remarkable and genuinely laudable about the console and its games. Fortunately, Jeremy Parish goes on a heroic crusade to set the record straight in the book Virtual Boy Works, which has entered its second edition at Limited Run Games and Press Run. This retrospective book details the origins of Virtual Boy, provides in-depth insights for all 22 games ever released (plus some that weren’t) for the platform, and even provides a snapshot of the homebrew and aftermarket scenes keeping the platform alive. All in all, Virtual Boy Works is definitive one-stop shopping for an education in Nintendo’s greatest failed experiment.

Virtually Perfect

The book begins with a seven-page overview of where the technology for Virtual Boy originated and how Nintendo decided to adopt it, and it provides a timeline of events up to and including the console’s discontinuation. The console launched in Japan in July 1995 and was discontinued by December, surviving only a few months longer in North America — an extraordinarily brief life span. Parish outlines how a gradual series of business decisions caused Virtual Boy to change from a wearable portable device to the bulky, barely portable device that landed on shelves, which contributed to its abysmal sales.

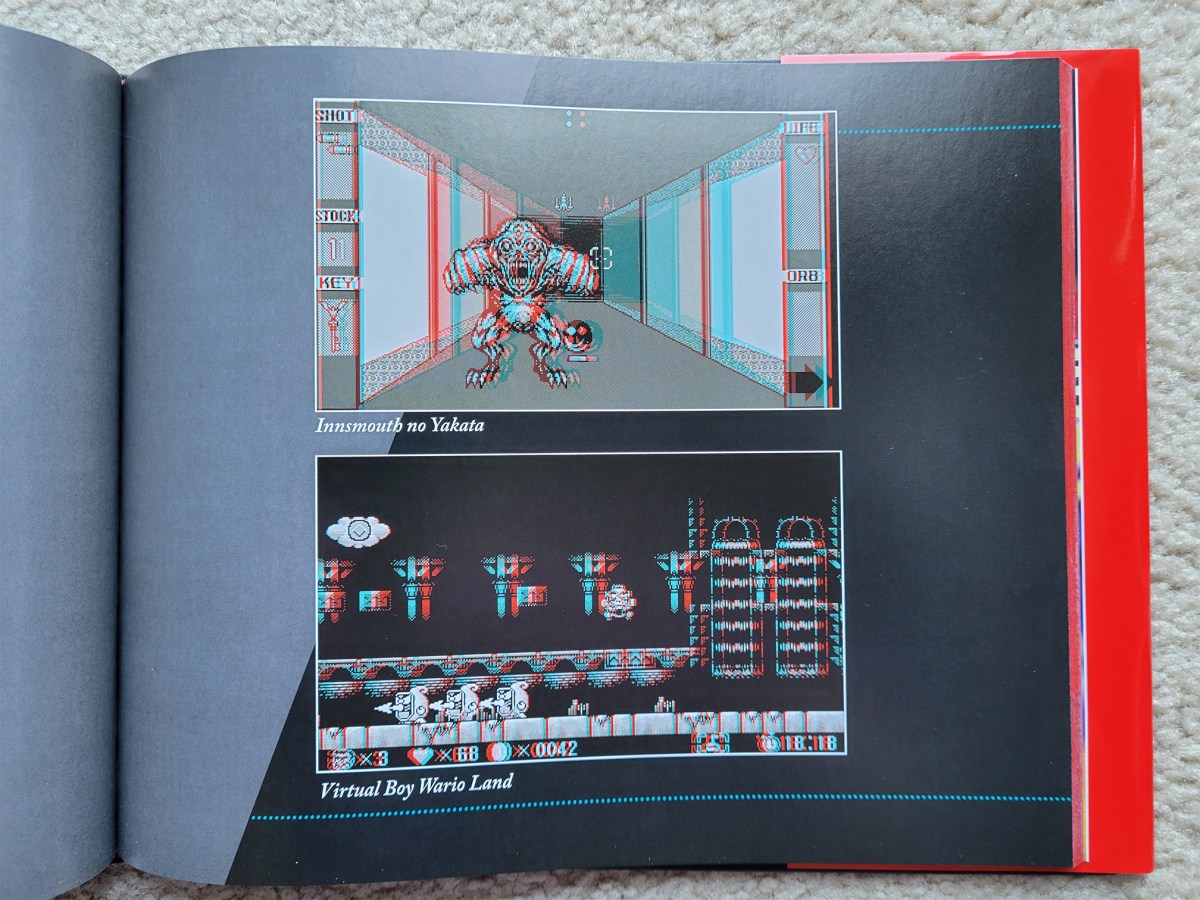

However, time and again in its analysis of the 22 games, Virtual Boy Works also demonstrates how the platform could muster some pretty cool visuals, 3D effect or not. Notably, although Virtual Boy was limited to four shades of red, reminiscent of Game Boy’s four colors, it actually had more power under the hood than a SNES. This often meant games had huge sprites, beautifully detailed and animated in a way that you just didn’t see on Nintendo’s prior platforms. The massive robots of Teleroboxer or just Wario’s sprite in Virtual Boy Wario Land are great examples.

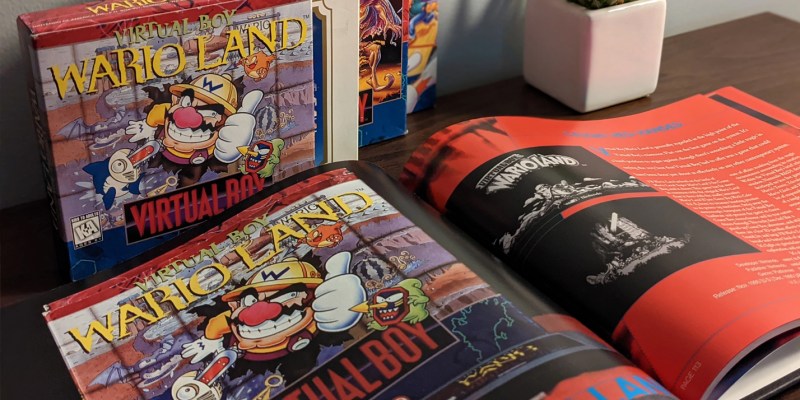

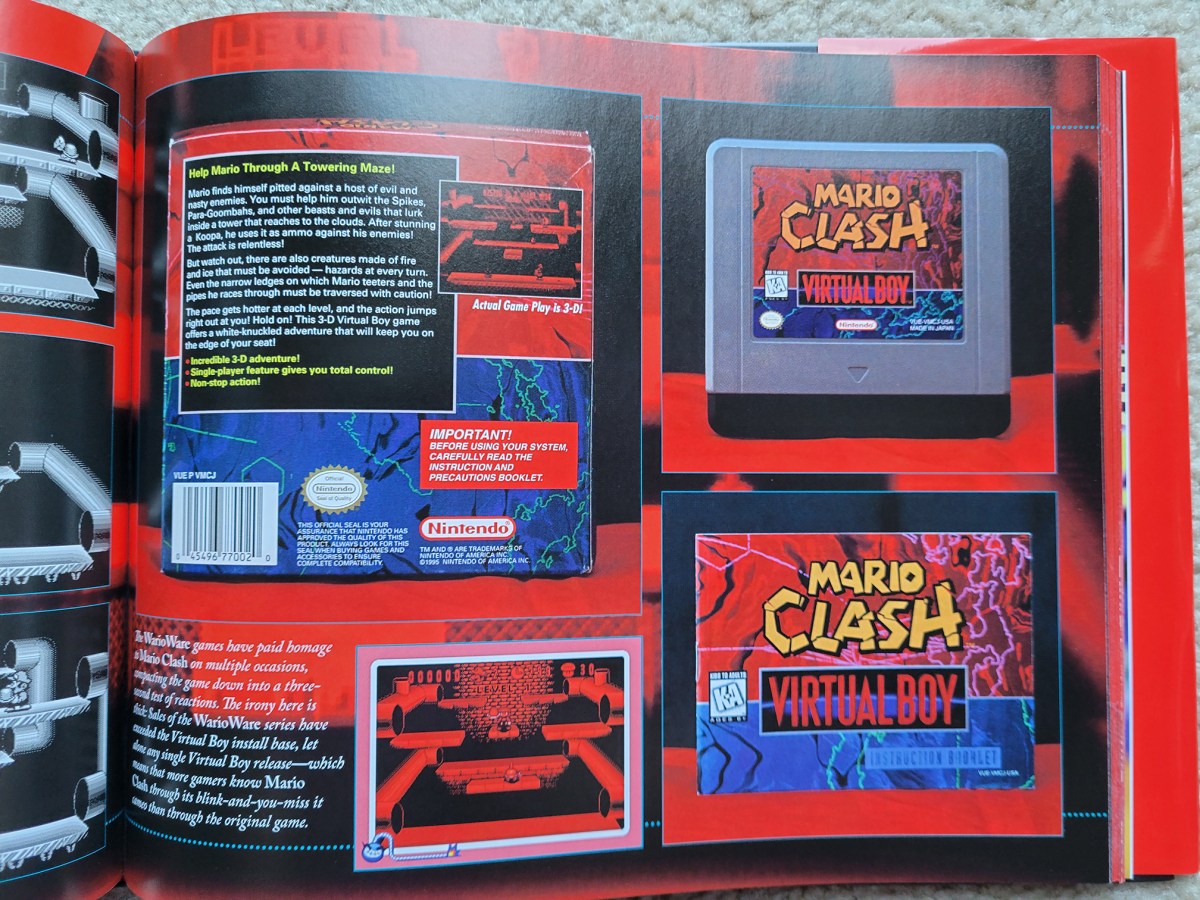

Virtual Boy Works goes to great lengths to offer high-fidelity glimpses of every game. For starters, Parish borrowed Chris Kohler’s personal Virtual Boy collection to take high-quality photos of all the game carts, their boxes, and their instruction booklets. Secondly, Parish used the enthusiast-developed Virtual Tap to capture direct-feed “raw graphical output” screenshots of every game, which means they are all completely unaltered (and, incidentally, grayscale). Lastly, just for fun, the middle of the book includes a “3D gallery” prepared by Benj Edwards, where you can put on the 3D glasses included with the book to get a tease of what each Virtual Boy game actually looks like when playing. It’s not perfect by any means, but it’s a delightful extra touch.

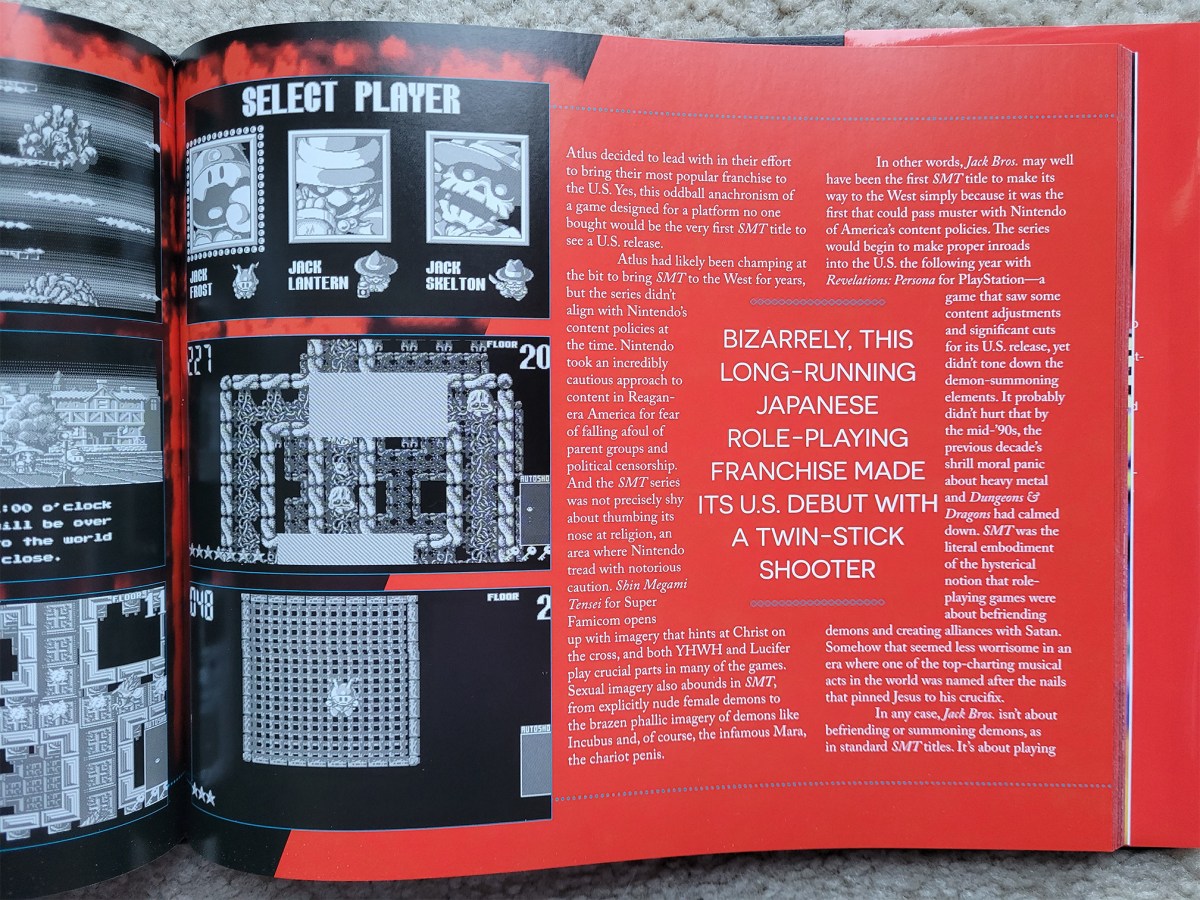

Beyond just providing a lot of informative imagery though, Virtual Boy Works’ greatest strength is how Parish puts all the pieces together. Each Virtual Boy game receives discussion proportionate to how much there really is to talk about, and Parish places each in its historical context to fully express how impressive or atrocious a game is. For instance, Atlus’ Jack Bros. (weirdly the first Shin Megami Tensei game ever released in the West) is basically a high-quality twin-stick shooter from before twin sticks were a thing, and it provides an excellent justification for Virtual Boy’s unique controller that presciently contained a control pad on either side. Parish also explains why quirky games like Mario Clash, Wario Land, and Teleroboxer ended up on Virtual Boy in lieu of similar-playing, more recognized franchises like Mario Land and Punch-Out!!. (It had to do with Nintendo development teams not wanting to encroach on each other’s turf.)

And once Virtual Boy Works is finished elucidating the platform’s entire games catalogue, English and Japanese, it then briefly touches upon enthusiast-made aftermarket accessories and homebrewed games. The aforementioned Virtual Tap is discussed, in addition to an arcade stick. If an arcade stick sounds like a strange thing for a platform with no fighting games, well, it becomes less strange (slightly) once you discover an anonymous person created a fully playable Virtual Boy version of Street Fighter II: Hyper Fighting, which the book also discusses. Virtual Boy Works really captures how the console is just so strange and so dead that it paradoxically ensured it would continue to live among enthusiasts.

Use the included 3D glasses to enjoy the 3D gallery!

Any criticisms that can be directed at the book are minor and trivial. Parish repeats himself from time to time, which is in part a consequence of this book being adapted from his Virtual Boy Works YouTube project. Almost none of the pages are numbered either, which makes relocating your spot a little bit more challenging. And naturally, Virtual Boy Works cannot capture every factoid under the virtual sun, but it makes an honest effort to collate all available information.

The Review Verdict on Virtual Boy Works

Ultimately, Virtual Boy Works lives up to the text on its book jacket. It really is “the definitive retrospective” of Virtual Boy and its library as it paints a complete picture of the console’s failures, innovations, and precious few triumphs. All Nintendo fans and gaming history enthusiasts should add Virtual Boy Works to their library.

A review copy of Virtual Boy Works was provided by the publisher.