This discussion and review contains some spoilers for Willow episode 3, “The Battle of the Slaughtered Lamb,” on Disney+.

Obviously, Willow takes place decades after the feature film of the same name, having allowed enough time to pass for the main characters to have and raise children of their own. However, it is striking how true the show is to the spirit of the original film and the filmmakers who produced it. All of that is to say that, like many of the big films of the 1970s and 1980s, beneath all its fantasy trappings, Willow feels like a story about divorce.

Willow was a project of George Lucas, one in the wave of filmmakers who emerged as part of the “New Hollywood” movement. His contemporaries included directors like Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, and Brian DePalma. Many of these filmmakers constructed elaborate and affectionate homages to the stories they had loved as children. After all, Lucas has acknowledged Star Wars was a love letter to war movies, samurai films, and science fiction serials.

These stories also reflected more personal experiences for these filmmakers. Many of these experiences were filtered through the prism of familial dissolution. Richard Brody has noted “the vanishing first wives” in the films of Martin Scorsese, following his early divorces. Many critics have noted the absent fathers in the films of Steven Spielberg, with James Lipton arguing that the climax of Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind was a plea for reconciliation between his parents.

Of course, divorce was a major preoccupation within wider 1970s cinema. In 1979, two years after the release of Star Wars heralded the arrival of the modern blockbuster, the highest-grossing movie of the year was divorce drama Kramer vs. Kramer. It was a bona fide cultural phenomenon, sweeping the Oscars. Ingmar Bergman’s television miniseries Scenes from a Marriage had a similar impact, to the point that it was blamed for inspiring real-life marital breakdowns.

There is a reason for this singular fixation. As governor, Ronald Reagan had signed no-fault divorce into Californian law in 1969, a decision he would later categorize as “one of the worst mistakes he ever made in office.” Similar laws were quickly enacted across the United States. The effects were immediate. While only 11% of children in the 1950s witnessed their parents divorced, approximately half would experience parental separation during the 1970s.

Notably, the proportion of men seeking a divorce jumped dramatically. In single-parent households, the absent parent was “typically” the father. This perhaps explains the prevalence of the absent father in pop culture of the era, even in stories that are not literally about familial dissolution. Luke Skywalker’s (Mark Hamill) relationship to Darth Vader (David Prowse, James Earl Jones) in the original Star Wars trilogy is an obvious example of a child confronting an estranged father.

Of course, Joseph Campbell argued that “atonement with the father” was a part of the classic mythic structure, but the films of the 1970s and 1980s placed that atonement in the context of familial collapse. Speaking specifically about George Lucas, the filmmaker’s 1980s were largely defined by his high-profile divorce from Marcia Lucas. The divorce was announced to the public the month after the release of Return of the Jedi and informed the darkness of Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.

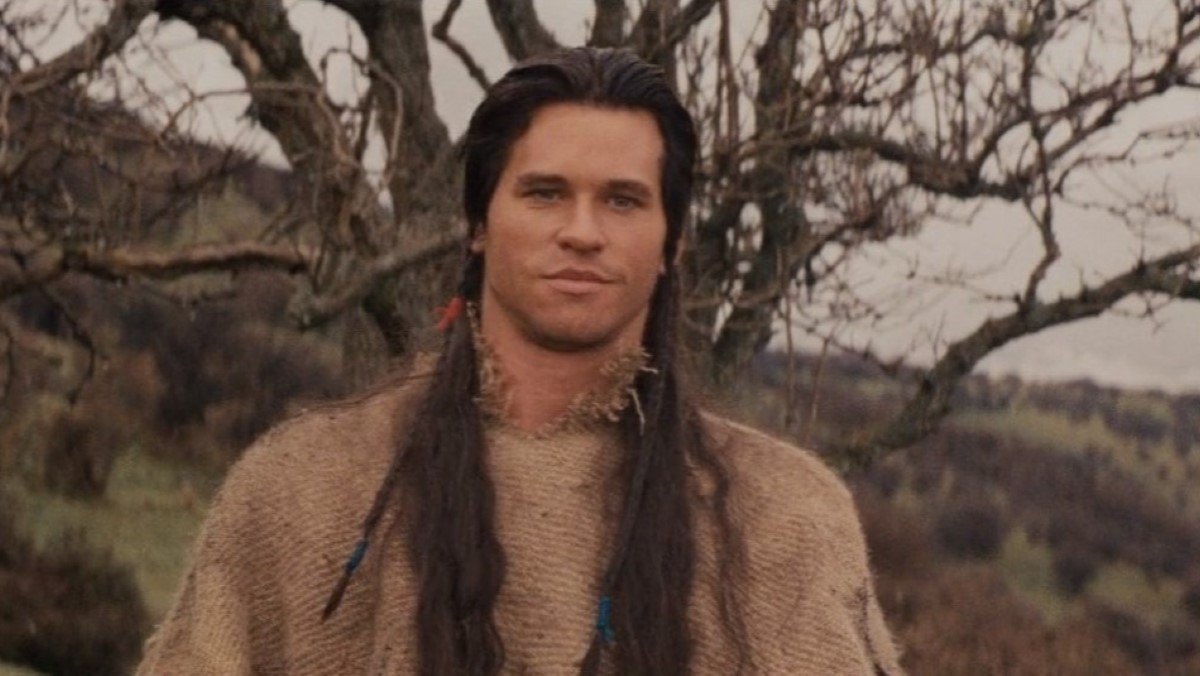

“Divorce is a very powerful thing,” Lucas told The New York Times as Willow entered release. “It’s changed what I thought was important. For the first time, my daughter has a priority higher than my work.” Perhaps it is not a coincidence that Willow is the story of an unconventional family unit, built on obvious antagonism between Sorsha (Joanne Whalley) and Madmartigan (Val Kilmer), that comes together to protect an innocent and vulnerable child.

With all of that in mind, it makes sense that the Willow television series should return to the theme of divorce and familial separation that informed so much of George Lucas’ work and that of his contemporaries. While Willow is obviously a very old-fashioned fantasy quest narrative, it is perhaps best understood thematically as a story about divorce from the perspective of children caught in the middle of that very fraught and very uncomfortable relationship.

Much of the show’s emotional core is driven by the absence of Madmartigan, who seemingly abandoned his wife Sorsha and their children Kit (Ruby Cruz) and Airk (Dempsey Bryk) to pursue “the Kymerian Cuirass,” what is essentially “a magical breastplate.” Of course, it seems likely that Willow is building to a major revelation that will recontextualize this narrative and reconcile the family, but the story established in the opening three episodes is that of an absent father.

Madmartigan’s absence is an essential part of Kit’s character. Kit is frustrated over Sorsha’s appeals to obligation and duty in “The Gales,” resenting her father’s abandonment of his own commitments. It informs her anger at Dove (Ellie Bamber) in “The Battle of the Slaughtered Lamb,” with Boorman (Amar Chadha-Patel) wryly noting, “You know, if she could actually do anything, then I’d say you were maybe being too tough on her, you know, maybe even punishing her for your dad leaving?”

Boorman is obviously the show’s surrogate for Madmartigan, given Val Kilmer’s well-publicized health troubles. Boorman is a rogue and a trickster, like Madmartigan. He was also Madmartigan’s squire. There is some suggestion that Sorsha’s decision to lock him in the castle’s dungeon is a way of punishing her absent husband by proxy. Even Boorman concedes that Madmartigan’s absence is key to the current mess, musing, “If he were alive, if he’d come back, things’d be different.”

Madmartigan isn’t the only example of this theme. “The High Aldwin” presented Willow (Warwick Davis) and Sorsha as bitter parents feuding over the best interests of Elora Danan, the child whom they both rescued together in Willow, to cement the divorce metaphor. At one point, Willow starts sneaking visits to see Elora without Sorsha’s knowledge or consent. Caught and humiliated, he screams in the courtyard like a father denied visitation, “She’s as much mine as she is yours!”

Willow is built around the observation that these sorts of separations and absences have a profound impact on the children caught in the middle. After all, even healthy and amicable divorces have a profound impact on the children involved. At its core, Willow is the story of a bunch of children who are the products of dysfunctional or absent parents, forced to make their way in the world with only surrogate figures like Willow or Boorman to guide them.

In “The Gales,” Ruby (Erin Kellyman) frames “the Barrier” as the kind of shield that parents create to keep children safe from the outside world. “It’s a forcefield, forged by Raziel and Cherlindrea to protect the realm,” she offers. “It was a refuge for those who wanted a life that was more than just survival.” Jorgen Kase (Simon Armstrong) makes this more explicit, explaining it was specifically to protect one child, “It wasn’t built to protect the realm; it was built for Elora Danan.”

Willow is built around the primary fear that parents caught in these sorts of struggles have been unable to put the best interests of their children ahead of their own egos. In “The High Aldwin,” Willow laments that the “something very special inside” of Dove, who was secretly Elora Danan, was not “nurtured,” but was instead allowed to “dissipate until there was nothing left.” In some ways, the petty struggles between Willow and Sorsha cost Dove her potential.

Sorsha has provided materially for her children. However, Willow suggests this overprotectiveness has prevented their children from reaching their potential. “You’re all so naïve, it’s adorable,” Boorman warned the group in “The Gales.” “You’ve never known pain, fear, hunger. When we get out there, it’s not going to matter who your parents are, or what you think you deserve, because the world is bigger than you can possibly imagine… and it doesn’t give a damn about any of you.”

“The Battle of the Slaughtered Lamb” foregrounds these themes, as the ensemble is forced to work together to recover Dove from the possessed Ballantine (Ralph Ineson). The group is forced to put their differences aside to prioritize the safety of a child. Notably, Willow insists that the group cannot split up if they are to succeed. Naturally, Boorman and Kit break off from the surrogate family unit. Boorman was Madmartigan’s squire, while Kit is his daughter. They learned from him.

Fleeing Ballantine, Dove stumbles across two women in the forest, Hubert (Hannah Waddingham) and Anne (Caoimhe Farren). These two women react instinctively to a lost child being chased by an evil force. Without any prior knowledge or allegiance, these two women living in a cottage in the middle of the forest commit to keep her safe. Acknowledging the prophecy of Elora Danan, Hubert muses, “We are obligated to protect it and, if needs be, die for it.” They ultimately do both.

This aside with Hubert and Anne is an interesting aspect of “The Battle of the Slaughtered Lamb,” introducing two one-shot supporting cast members who are promptly killed off — one of whom is played by the co-lead on one of the biggest sitcoms on streaming. It is a choice that feels thematically important to Willow. The functional and loving relationship between Hubert and Anne, along with their willingness to put a child ahead of their own desires, serves as a pivotal contrast.

As befitting a television spinoff from a 1980s fantasy film, Willow is ultimately a story about parents and children. Crucially, it’s a story about how these parents really owe their children a lot more than they’ve given them.